Pressures of wrestling can exacerbate mental health issues

This story or pages it links to discuss suicide and depression which may be upsetting to some people. If you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or need someone to talk to, please skip to the bottom of this article for resources or head to our Mental Health Resources page now.

When Ryan Millhof woke up in the emergency room at Tempe (Arizona) St. Luke’s hospital, he was groggy, confused, and being closely monitored by a slew of doctors. But, he was not alone.

The smell of antiseptic burned his nose as he slipped in and out of consciousness. Each time he woke, it was to a new face sitting beside his bed. No one would ask the question, but each of his visitors’ faces spoke louder than any of the words they could have uttered. Why?

On Jan. 21, 2019, the Division I All-American wrestler downed a cocktail of anti-anxiety medication and muscle relaxers in an attempt to take his life.

After experiencing nearly two decades worth of the highs of victory, the disappointment of defeat, the years of sacrifice and countless injuries caught up, and it seemed like the only way out to the then 23-year-old Millhof who wrestled for Arizona State.

“When you take a bunch of medication or try to hurt yourself or whatever it is that you do, your world seems very, very small,” Millhof said.

“You’re focused on all of the negative aspects and the negative identities you associate yourself with. When you come to, and you’re in the hospital, you see the world around you and you grasp the magnitude of the situation.”

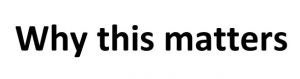

The magnitude of the situation is significant. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), one in every five Americans will suffer from some form of mental illness at some point in their lives.

But Millhof is more than a statistic. He and an inexhaustible number of athletes within the sport of wrestling are living examples of the reality of the systemic shortcomings of mental health in athletics.

A study found that collegiate athletes have a 10%–15% chance of developing a mental illness severe enough to warrant counseling, which is 2% higher than their non-athletic counterparts.

According to the NCAA, there are more than 460,000 student-athletes currently participating in 34 different sports.

If those numbers hold true today, then the population of current student-athletes who will battle a mental illness while juggling the demands of being an athlete would fill nearly any MLB stadium: 46,000 people, give or take a few.

With an issue as complex and individualized as mental health, it’s difficult to identify a singular problem or simple solution. When a stigma becomes socialized and so ingrained in how we function as humans, it’s difficult to separate the assumptions associated with a stigma from fact.

But, the facts are simple: student-athletes are suffering, at a shocking rate, from mental illness — and oftentimes, no one notices until it’s too late.

“You’re focused on all of the negative aspects and the negative identities you associate yourself with. When you come to, and you’re in the hospital, you see the world around you and you grasp the magnitude of the situation.” - Former Arizona State wrestler Ryan Millhof

Kristin Hoffner is a principal lecturer at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions. Her research areas include sport psychology, coaching behaviors, team cohesion, performance psychology, and self esteem, among a number of other areas related to sport.

“When we look at NCAA Division I athletics, specifically, I think most people can immediately understand the high level of training, the high commitment,” Hoffner said. “With that can come very high levels of staleness, which is the precursor to burnout.”

Burnout is the term used to describe the psychological and physiological issues associated with the high-level demands of athletics with little opportunity for recovery. Often, a lack of recovery leads to an injury or performance slump.

“Performance slumps can then be wrapped into anxiety, attached to fear of failure,” Hoffner said. “They can start to manifest in depressive episodes because, for a lot of Division I athletes and really all athletes, it’s a big piece of their identity.”

Preserving this identity, in many cases, is a principal factor when considering the success of the athlete.

“When your identity starts to suffer, that can consistently kind of pull up the same kinds of things that are associated with depression and anxiety,” Hoffner said.

The depths of depression

The sport of wrestling, just like any other collegiate or elite-level sport, demands a unique level of discipline, work ethic, and intrinsic accountability.

The demands of higher education paired with the complex structure of the athletic lifestyle leaves very little time for student-athletes to be anything outside of these identities.

“When I started getting to a higher level of wrestling (that) is when my depression and anxiety started becoming more noticeable,” Millhof said. “You’re dealing with higher-level emotions, physical aspects, schoolwork, and personal life.”

Injuries plagued Millhof’s 18-year career. Each injury and time away from the mat was a blow to the identity that Millhof had constructed for himself as an athlete. Just one month into the final season of his career, the 125-pound wrestler sustained a severe concussion, which changed the landscape of how he navigated his identity entirely.

“As someone that has struggled with anxiety and depression in the past, we know scientifically, concussions can raise those symptoms,” Millhof said. “I wasn’t able to get back on the mat as fast as I had wanted, and I put my all into wrestling but I couldn’t even compete.”

“I felt worthless.”

“When we look at NCAA Division I athletics, specifically, I think most people can immediately understand the high level of training, the high commitment. With that can come very high levels of staleness, which is the precursor to burnout.” - Kristin Hoffner, principal lecturer in Arizona State's College of Health Solutions

Millhof added that the concussion affected the way he thought, acted on a daily basis and interacted with friends and family. He said his thought process suffered, and the overall way his body felt was concurrent with his head injury: unpredictable.

Arizona State assistant wrestling coach Chris Pendleton noticed a change in Ryan’s behavior, but said that “the scary part is that it’s actually kind of normal for any athlete who has an injury because they’re isolated and away from the team.”

The NCAA Sport Science Institute lists a number of symptoms that are identified as “normal behavior” for an athlete to exhibit after sustaining an injury. Almost every symptom listed can also be interpreted as a symptom that is associated diagnostically with a depressive episode or disorder.

So how do athletes, coaches, and medical personnel distinguish between what is considered normal by the NCAA, and what is actually concerning behavior?

Coaches, athletic trainers, and athletes themselves cannot be expected to recognize changes in an athlete’s behavior, and what that change in behavior might mean. The normalization of symptoms that are synchronous with warning signs for serious mental conditions, however, can be more of a danger to an athlete than the condition is itself.

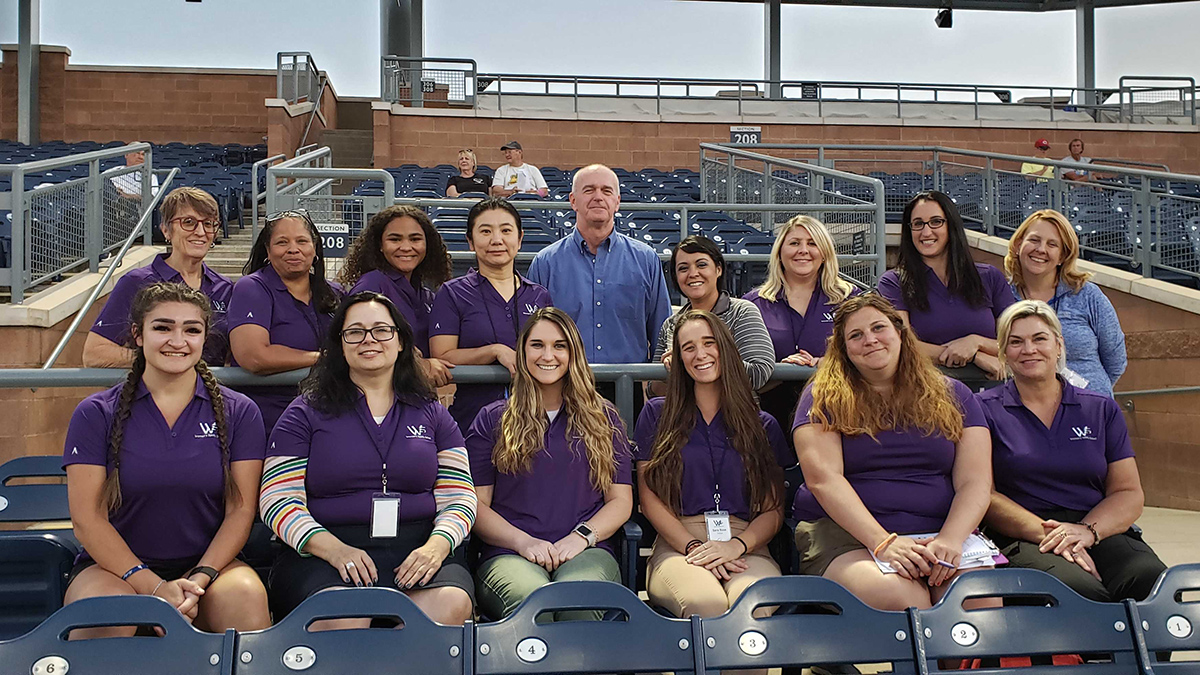

Penn State’s Kyle Conel, an All-American who previously wrestled at Kent State, said he has also been wrestling with depression since “sixth or seventh grade.”

While wrestling remained the single constant in his life, the highs and lows of the sport and the pressures he faced as a result of the sport, and life in general, destabilized his emotions.

“I kind of always knew that I had depression,” Conel said. “I just never went to a doctor for it, never talked to anyone about it. I just kept it to myself and kept everything bottled up.”

In the spring of 2016, coming off of what he described as a “spectacular redshirt-freshman season” at Kent State, Conel attempted to take his own life.

“It almost didn’t feel like I was a real person,” Conel said. “I was just going through the motions, in pretty much every part of life.”

Kyle’s depression seeped into nearly every area of his life, and it came amid other stressors in his life, including pressure from coaches, teammates, and fans of Kent State to carry on the legacy of success the program has for producing All-Americans.

“When I was at my worst point, I pretty much would just wake up, go to my workouts, go to class, and then go home,” Conel said. “When I would go home, I was so stressed out and depressed that I would basically stare at the wall until I went to bed.”

Conel woke up 16 hours after ingesting an entire bottle of pills he had been prescribed after a surgery. He got up and went to his team’s weightlifting session, “just like nothing had happened.”

Luckily, Conel survived and in the aftermath, he confided in someone. After speaking with one of his academic advisors, Kyle got the help he needed to cope with his daily struggles.

He stepped away from the sport for a handful of months, but made the decision to return to the mat, despite knowing he would have to win back his teammates and coaches.

“Getting back into wrestling, I had a lot of pushback from my support system, which caused a lot of stress,” Conel said. “Some people really didn’t respect me for leaving the team. I was basically trying to win everyone over, which was stressful.”

The 197-pound wrestler from Ashtabula, Ohio capped of an impressive redshirt-junior campaign by knocking off the No. 1 seeded wrestler not once, but twice, en route to a third-place finish at the 2018 NCAA Division I Wrestling Championships.

But no amount of success, even in one of the most grueling weekends in sports, could fend off the depression that awaited Conel once he stepped off the medal podium.

“When I was at my worst point, I pretty much would just wake up, go to my workouts, go to class, and then go home. When I would go home, I was so stressed out and depressed that I would basically stare at the wall until I went to bed.” - Penn State wrestler Kyle Conel

“After that tournament, I probably went into one of the worst depressions of my life,” Conel said. “The hype and the attention was cool, but it got to be really overwhelming. I couldn’t focus on my school work. My academics definitely suffered.”

In addition to competing at the Division-1 level, majoring in computer science, and working in tech support for Kent State’s campus, the 23-year-old also served as a primary caregiver for his niece and two nephews.

“I was busy from before sun up until sun down; all day, every day. That was another hard thing where I didn’t have as much time to relax,” he said.

Conel added that a change in his mindset toward wrestling helped him appreciate the fact that he was able to compete in a sport that so many could not. He said that appreciation helped illuminate other areas of his life.

“I went into it with the mindset that I was doing it for myself, I wasn’t doing it for the people who have bad things to say about me,” Conel said. “I went in with the mentality of doing this for myself and being grateful for every single day – the hard days, the easy days – I’m grateful that I have them.”

He completed his degree at Kent State University. After sustaining an injury his senior year, he was granted a medical hardship waiver from the NCAA, and used the graduate transfer rule to join the Nittany Lions’ powerhouse wrestling program this season.

Identifying with injury

An injury can happen at any moment and everything can change for athletes when they occur. Some of the most common injuries for wrestlers include ligament tears in the knee, dislocations or sprains to the elbow or shoulder, fractured and dislocated fingers and concussions.

Some injuries are easier to cope with than others. But the one thing that ties all injuries together is what is required mentally for the athlete to completely recover.

Sarah Hildebrandt is a resident-athlete at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs and an alumna of the highly-decorated King University women’s wrestling team. She won two national titles for the Tornado at 123-pounds.

Injuries have accompanied Hildebrandt through most of her career; one of the many challenges of the sport she has found difficult to cope with through the years.

“You do something your whole life, every single day, everything revolves around it and then just, boom, it’s gone,” she said. “You’re told you can’t do it for six or seven months.”

Prior to the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials, Hildebrandt suffered a knee injury. Two meniscus tears meant two more hurdles to clear in order to qualify for the Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

“You do something your whole life, every single day, everything revolves around it and then just, boom, it’s gone. You’re told you can’t do it for six or seven months.” - Olympic-hopeful wrestler Sarah Hildebrandt

Hildebrandt lost in the second round, ultimately placing fifth at the Trials. Helen Maroulis, who won the 53kg class that Hildenbrandt competed in, went on to become the first gold medalist in women’s freestyle wrestling for the United States.

“Recovering after that was an unreal feeling. I remember I just kept thinking, ‘four whole years,’ ” Hildebrandt said. “I knew there was no way I could make an Olympic team when I’m out of commission halfway, and that was just straight heartbreak.”

Hildebrandt said one of the most difficult aspects of coming back from an injury is recovering mentally from the pain and disappointment.

“You’re kind of forced to think, ‘Who am I outside of wrestling?’ and that can be really scary,” she said.

The time between the heartbreak of Hildebrandt’s 2016 run and her next appearance on the 2018 world stage was driven by a transformation of both mental and physical practices that would set her apart from the rest of the competition.

“I think (injury) ends up being beneficial for my performance,” Hildebrandt said. “As the months go on, I’m kind of able to realign my emotions, find silver linings and actually come back to the sport much stronger.”

She went on to become the World Team member representing the U.S. at 53kg, bringing a silver medal home from the 2018 World Championships in Budapest, Hungary.

Hildebrandt was named the 2018 Women’s Wrestler of the Year by USA Wrestling, and recently defended her third career spot as a senior World Team member in June.

Hildebrandt said she used her time away from the mat to reform the ways she thought about, and functioned within, the sport. She made monumental changes to her diet to make cutting weight easier, and chose to prioritize her health over anything that wasn’t making her a better wrestler.

She said the injuries she faced forced her away from the wrestling room and served as necessary mental breaks Hildebrandt didn’t even know she needed.

“Are you really taking time off if during your time off, all you’re thinking about is how you should be working out and you should be eating this and doing that?” Hildebrandt said.

“That’s not taking time off, and it’s mentally exhausting. When you’re experiencing anxiety from this sort of worrying, that’s not a break. Sometimes injuries end up being really good for people because it forces you into this time off and, whether you like it or not, you can’t be in the wrestling room.”

A fixation on food

Food is one of the most basic human needs. But when a sport is centered around the number that is displayed when an athlete steps on the scale, food goes from a thoughtless essential for most people to an obsession for a wrestler.

Cutting weight is often inevitable in wrestling. Athletes are disqualified from competition if they are even an ounce over their designated weight at the time of weigh-ins. So for many wrestlers, weight becomes a central focus.

In a 2007 mental health manual produced by the NCAA, participation in sports “for most individuals is a healthy experience, but aspects of the sport environment can increase the individual’s risk for an eating disorder.”

But what happens when behavior that would normally be considered abnormal is a foundational trend within a sport?

Rachel Watters is a wrestler at Oklahoma City University (OCU) and a five-time age-group World Team member for the United States. She currently is second on the ladder for the women’s senior-level national team.

Although Watters said she thinks she’s been depressed for a while, she said that cutting weight heightens all of her feelings associated with depression.

“I just remember having a really, really bad experience with it when I was cutting weight in high school,” Watters said. She used to have to cut as much as 15 pounds while wrestling in high school against boys in Iowa.

“I would be doing 12-pound swings from Sunday to Thursday, for months,” Watters said. “So that was where it got really, really bad, and where I realized I needed help.”

Watters recalled a night that she was in bed, unable to sleep because of dehydration. “My brain was just racing, and I remember feeling suicidal. I think it was definitely heightened because of the cutting weight.”

Watters was able to balance her weight expectations alongside her academic requirements during her freshman year at OCU, but it didn’t come easily.

“I was cutting pretty hard weight, classes were way harder, I was traveling a lot our freshman year,” she said. “My first ever finals week in college, I was cutting weight for the U.S. Open, which was in a matter of days.”

What made it worth it for Watters was the strong foundation and support system. Central to that system is her coach, Matt Stevens.

“He cares about you as a human being first, before wrestling,” Watters said, adding that having the support of her coaches made dealing with injuries, depression, and the struggles of weight management bearable.

Hildebrandt cited a similar experience with the strong support she gets from her coaches, fellow athletes and family, and how this has helped her combat her own mental hurdles.

“I definitely struggle with body image issues,” Hildebrandt said. “I think that’s a huge part of my mental struggles. I have my whole life. Before wrestling I was a ballerina, another sport where the body is so analyzed, especially as a woman.”

Whether Sarah was battling issues within the realm of confidence and worth or weight management and image, her coaches were there almost every step of the way.

“I think having worked with them for so long, I do feel comfortable enough to turn to my coaches and tell them that mentally, I’m not here right now and I can’t be doing this,” she said. “Or even on the other end, I think they know me well enough to know when I’m not okay.”

Hildebrandt said that she struggled with her weight, self-image, and mental health through college, which helped lead to her decision to leave school and become a resident-athlete at the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

“My junior year of college was when I won my first college national title and mentally I never felt worse,” Hildebrandt said. “It’s very clear that winning is not the answer to things you might be dealing with.”

In a sport where weight precision and body composition is the central focus, it’s hard for some athletes to see anything other than how many meals they might need to skip when they step on the scale.

“My junior year of college was when I won my first college national title and mentally I never felt worse. It’s very clear that winning is not the answer to things you might be dealing with.” - Olympic-hopeful wrestler Sarah Hildebrandt

“You have to look at it, the number does matter,” Hildebrandt said. “On top of that, we kind of have almost bred this idea of, if you go down a weight class, you’ll be more successful. So, you’re too big, but go lose 20 pounds and then put on your one-piece Spandex singlet and you’ll be successful. It’s terrifying.”

Hildebrandt thought back to when she was in college; when she would win matches and have her arm raised, she would make sure to cover her torso with the other arm so that no one would be able to photograph her stomach through her singlet.

“I would remember to do that in the heat of the moment, seconds after winning a match,” she said. “Those pressures are there, and I think they do weigh deeply on a lot of athletes. We’re told our body needs to look like this, and we need to be this strong, so you need to cut this much weight.”

The unrealistic body image expectations and pressures that weigh deeply on an athlete, regardless of the sport, know no gender.

According to the NCAA, eating disorders “are much less common among males, but it should be remembered that 10 to 25 percent of individuals with eating disorders are male.”

Eating disorders are a sensitive topic, especially for athletes, making intervention and treatment exceedingly difficult within an already-existing exercise regimen and training cycle.

The pressure to perform

Gianni Ghione had his first-ever anxiety attack after sustaining a shoulder injury during wrestling practice at the University of Pennsylvania.

“If you’ve never had one, they’re absolutely terrifying,” Ghione said. “You literally think you’re dying because you don’t know what’s happening to you.”

Then came the concussions. Ghione suffered two concussions within the span of a few months, each within minutes of his return to the mat from the previous injury.

“I want to say that was rock bottom, but it wasn’t,” Ghione said. “It definitely got worse.”

Ghione said the stress caused a spike in his anxious tendencies and stemmed from a combination of his expectations to perform athletically and academically at an Ivy League university.

“My anxiety was at its peak. I was having multiple panic attacks a day, back to back,” Ghione said. “I lost 20 pounds in what felt like a week. I told myself I couldn’t live like this anymore.”

Chas Dorman, associate director of athletics communications at Penn, has worked for the Quakers for a decade, spending much of his time and energy on the wrestling program.

“Penn is a place, across all sports, that is very high stress because there’s a lot of pressure,” Dorman said. “We’ve had some really tough experiences at the university, and within the athletic department. So, we’re trying to get as many resources together as we can to let our student-athletes know that battling through mental health issues is a fight worth winning.”

The Penn trains its community of faculty, athletics administration, and students to provide iCare, which the school calls a “first level of care.”

iCare has helped train nearly 3,000 people since its launch in 2014 in the areas of crisis intervention and general education of mental health.

Through the training, Associate Athletic Director Matt Valenti served as a resource to Ghione while he navigated the unfamiliar areas his anxiety created.

Valenti is a Penn wrestling alum and a two-time NCAA champion and three-time All-American for the Quakers.

Ghione said that Valenti was one of the first people he called when his anxiety pushed him to what felt like a breaking point.

“He knew exactly what to say,” Ghione said. “He said, ‘Tell me everything. What do you need?’ ”

Working alongside his athletics administration and coaching staff, Ghione decided to go home to New Jersey before the end of his fall semester, hoping to return for the 2019 spring semester.

Ghione’s decision to take time away from both school and the sport led to a challenging time for reflection.

“Being around this level of competition, you have to have a certain level of perfectionism to your personality,” Ghione said. “When you expect a certain level out of yourself that’s so perfect, you’re never going to be good enough.”

Despite concerns surrounding his academic and athletic demands, Ghione ultimately took a leave of absence from the Penn in the spring of 2019.

"I never understood anxiety or panic attacks, so I understand when people just don’t get it. If you’ve never gone through it, you’re not going to get it.” - Penn wrestler Gianni Ghione

“When it came to my coaches, I didn’t know what to expect,” Ghione said. “I didn’t know if they were ready to deal with it, because not a lot of people know how to deal with this level of mental health issues.”

To his surprise, Ghione said that his coaches and the athletics administration were equipped with the tools to prioritize Ghione’s health while helping him keep wrestling in his life.

Ghione’s coaching staff and teammates kept in constant contact during his leave. The team sent photos from road trips, which Ghione said made him “still feel like a part of the team.”

His absence from his team is nearing an end, as Ghione is listed on the 2019–2020 roster at 133/141 pounds for the Quakers.

Ghione said he recognized the stigma surrounding mental health, and realized that “a lot of people don’t seek help because they don’t want to admit they’re dealing with something.”

“Before I dealt with this, I didn’t understand how crippling it all is. I never understood anxiety or panic attacks, so I understand when people just don’t get it,” Ghione said. “If you’ve never gone through it, you’re not going to get it.”

Ghione has used his own experience to shine a light on mental health issues. During his leave of absence, he published a statement to his Twitter account, applying transparency to his situation.

“At the end of the day, if you want to get better, it does have to start with you,” Ghione said. “You can’t let your mental health take over your life. You have to be willing to fight back.”

Cultivation of constructive culture

The topic of mental health has been evolving from what can be perceived as taboo to something that is becoming embraced within society.

Sport can act as a double-edged sword for many athletes, serving as a source of stress, but also as an outlet for negative emotions.

Regardless of the sport, student-athletes and elite-level athletes have one thing in common: their lives are filled with an overwhelming amount of pressure and stress.

Destigmatizing and socializing mental health in sport can be accomplished through a process involving breaking down sport as a whole into many layers.

Looking at the issue of mental health from microscopic perspectives, like that of a single sport, coaches, athletes, team dynamics, and so on, can help target treatment and training for those who can help prevent the adverse health effects mental health issues can pose to an athlete.

Hoffner said that when it comes to college and elite-level sports, the athlete-coach relationship extends beyond the boundaries of sport.

“I think that the coach not only plays a coaching role, but a mentor role as well,” Hoffner said. “To be comfortable or feel comfortable enough to be able to divulge any sort of illness – mental, physical, an injury – all of these things are critical to mental health maintenance.”

Pendleton said he feels the added responsibility every time he talks to the parent of an athlete the Sun Devils are recruiting.

“You know, coaching isn’t just the X’s and O’s of showing a wrestling move,” Pendleton said. “You are responsible for being that gap between them leaving high school and leaving their parents, to the real world. It’s a daunting job responsibility.”

Hoffner suggested that the ideal solution is athletic departments putting coaches through training that will help them recognize the warning signs of mental illness.

“We have a big stigma with mental health in this country, so if athletes are experiencing this, they’ve kind of been conditioned to not speak up,” Hoffner said. “That may also be something that is socialized within a sport setting as well. But, coaches aren’t trained in these sorts of things, so to go to a coach, or to go to a teammate, (an athlete is) not always getting the best advice on how to effectively deal with it. Not because of any sort of malintent, but because of a lack of knowledge and training.”

As this silent epidemic continues to plague millions of Americans, the first step is to start a larger conversation about reducing the stigma associated with mental health.

As Millhof reflects on his life since that night in the hospital, he believes “talking about it” was the best thing for his recovery, but he also recognizes that his words could have an impact on someone else. So, he decided to tell his teammates what he had been through.

“Being a male and being a wrestler you really try to shy away from emotions,” Millhof said. “You really try to be like, ‘I’m okay. If anything’s bad I’ll toughen up. I’ll deal with it.’ And what scared me is if one of my teammates went through it, and I could have said something to help them.”

For Millhof, what started simply as a concussion evolved into a wakeup call for him and those around him.

“I was one of those guys, that was like, it’s never going to happen to me,” Millhof said. “You are going through things, and that makes you human.”

Millhof has since learned how to live with the stressors that almost took his life. He spends each day coaching a high school team in his native Georgia, giving back to the sport which has given him so much in life.

He is a wrestler, a coach, a soon-to-be husband, but above all, a survivor.

Mental health issues are a real, but treatable illness, and you are not alone. If you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or need someone to talk to, please take action now by calling 1-800-273-8255 or by visiting suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

McKenzie Pavacich is a masters sports journalism student at Arizona State University

With any glimpse of a warm day in the winter, or the first sunny day that arrives in spring, there seems to be an unusually large number of people who head out for a run. For many though, this activity doesn’t last long. Shortly after those first few runs, knee pain ensues.

With any glimpse of a warm day in the winter, or the first sunny day that arrives in spring, there seems to be an unusually large number of people who head out for a run. For many though, this activity doesn’t last long. Shortly after those first few runs, knee pain ensues.