Wearable technology now knows if you are a candidate for diabetes

When the Boston Red Sox were caught in 2017 using an Apple watch to receive messages from the team’s video room about upcoming pitches there was an ah-ha moment for sports fans. Beyond the idea that teams were cheating to get an advantage (hello stealing signs, which has been going on since the invention of baseball), the reach of wearable technology went from something runners wore to track their workouts, to ways to get a competitive edge.

According to the New York Times, “The College Board, which administers the SAT and Advanced Placement tests, does not allow wearable technology such as digital watches or Google Glass in its testing centers. Neither does Law School Admission Council, which handles the LSAT.”

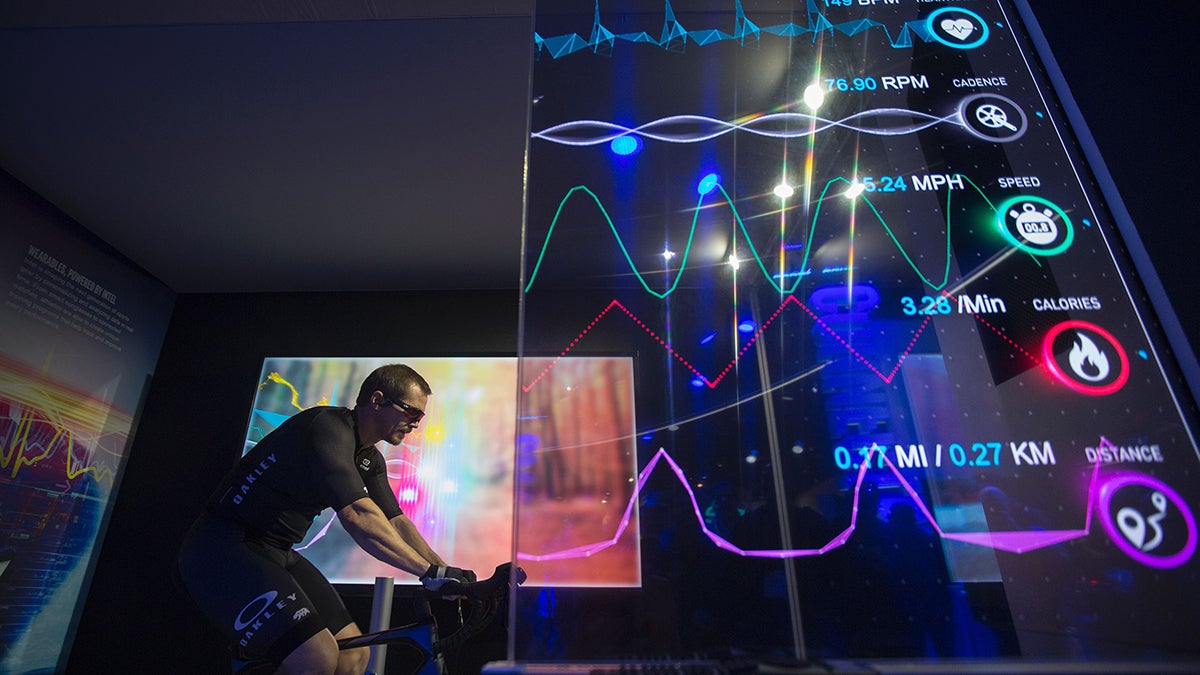

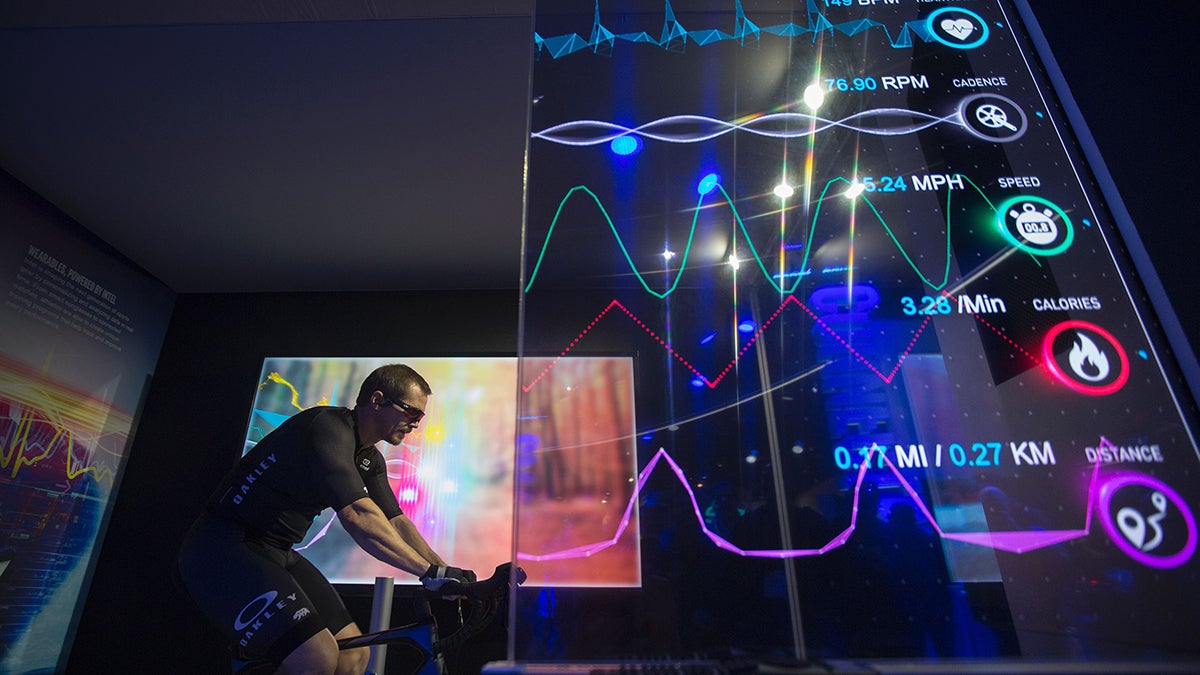

For athletes and administrators, utilizing wearable technology can give them an edge in training as well.

Take the new use of a mouthguard embedded with accelerometers to measure head impacts boxers take in real time. That technology is now being discussed by the NFL to measure head impact beyond what happens in the helmet.

“Development of the Intelligent Mouthguard has been guided by the hypothesis that trustworthy information on three aspects of head impacts — magnitude, location and direction/orientation (e.g., glancing blow vs. direct blow) — is necessary for effective concussion risk monitoring,” according to Consult QD.

The ubiquitous fitness tracker is also expanding beyond how many steps you take. In a study published in the medical journal PLOS Biology volunteers who wore commercially available trackers and participated in questionnaires about their lifestyle, had cardiac images taken as well as blood profiles draw were examined. The researchers found that the activity from the wearable tracker could predict certain markers in blood that have been associated with diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

At the same time as the new wearables are being integrated into helping determine heart health, issues of propriety and privacy arise. FitBit announced recently that the new Fitbit Ionic and Versa smartwatches will compile date from healthy women.

“There’s an amazing dearth of information about a healthy woman’s menstrual cycle. And this is because scientists tend to study diagnoses and diseases. It’s really hard to get a grant to study what’s normal,” said Katherine White, a Boston University assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology in SportTechie.com. “All of this data coming in from Fitibit’s global community of users is going to allow us to examine some of these relationships at a massive scale that we’ve never been able to do before.”

According to SportTechie, Fitbit has gathered one of the “largest databases of biometric data in the world with 116 billion hours of heart rate data, 6.5 billion nights of sleep, 102 trillion steps and 213 billion minutes of exercise tracked over the past decade.

Polar Team Pro utilizes a sensor that fits either in a pocket or around transmitter strapped to the athlete and tracks heart rate, speed, running cadence and deceleration. Coaches and trainers can use that technology to analyze performance and how their teams respond to specific workouts.

Some of this data sharing is intentional – runners post maps of their routes with their times, gym-goers share how many “points” they earned with a screen shot of their workout monitor – while other sharing is not what was intended. The fitness tracking app Strava showed where secret U.S. Army bases were located after the company released a data visualization map showing every single activity ever uploaded, including the unintentional display of military members’ running routes.

Omar Hassanein, the CEO of the International Rugby Players Association, said it is important for players to be in control of the data gathered by this wearable technology.

“We understand that this is new territory both for clubs and players and are working with all sides on that basis, however it is important that players are in control and consulted around any use of their playing data.

“We are liaising with clubs, unions and governing bodies on issues that arise,” Hassanein continued. “We believe players are entitled to manage their own private data with the same respect to their confidentiality that any other member of the public would be afforded.”

Not all wearable technology though is internet connected. For instance, Dr. John Cronin, of the Auckland University of Technology, who is the co-director of sports performance research institute at AUT is studying how light variable resistance training using small weights velcroed to the body in various positions can increase effective workouts and correct to proper form. Wearable does not have to mean connected!

From the move from cotton T-shirts to run in to the growth of specific shoes to compete in, GPS-connected watches to “fast” swimsuits to wicking clothing, or measuring an athletes’ energy expenditure wearable technology is a constantly changing and evolving field.

Finally, US Soccer recently announced a deal with STATSports to provide wearables to monitor its 4 million registered soccer players in the U.S.