Too tall, too short, too big: Athletes breaking body stereotypes

Why this matters

When children start to get serious about a sport and they don’t have the typical body type, is it helpful or harmful to tell them they’re not built for that sport?

Jack Bacheler stood 6 feet 7 and represented the United States at the 1968 and 1972 Olympics. He wasn’t a swimmer or a basketball player. He was a long-distance runner. In a sport that rarely sees elite competitors taller than 6 feet, Bacheler was a giant who made the finals of the 10,000 meters in 1968 and finished ninth in the marathon in 1972.

Although she was only 5-5, Svetlana Khorkina towered over other gymnasts. Despite her height, Khorkina won seven Olympic medals and 20 world championship medals.

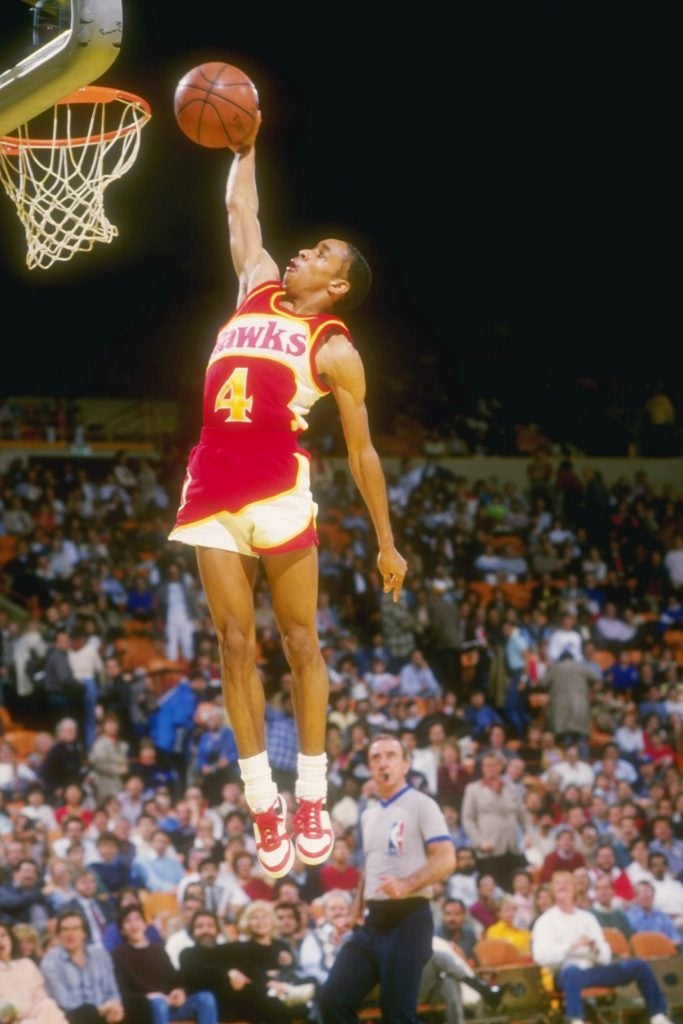

Spud Webb is famous for winning the 1986 NBA slam dunk contest despite being only 5-7. Webb was blessed with an otherworldly vertical leap, but he wasn’t a one-hit wonder. He played more than 10 years in the NBA and averaged almost 10 points per game.

How can athletes excel despite having an atypical body for their sport?

Kevin Alschuler, a psychologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, has worked with sports teams and conducted sports-related research on pain, discomfort and adaptation to extreme physical distress. He believes that athletes with atypical body types who succeed at elite levels do so because they have optimized everything else.

“For an athlete to perform at their best, if they’re at the highest level especially, they have to have the complete package,” Alschuler said. “They have to have the physical side; they have to have the psychological side. They have to have the skill, the strategy, the nutrition. All those pieces have to come together.”

Another observer of such athletes is Keith Baar, a professor of molecular exercise physiology at the University of California, Davis. “There’s nothing inherent about being tall, for example, that is going to make it that you shouldn’t be a good runner. In fact, the longer your legs, the lower the cost of transport,” Baar said. “It’s really about the weight that’s associated with those things. If you have long legs and smaller feet, you’re [former marathon world record holder] Paul Tergat.”

The distribution of weight on an athlete’s body and the relative size of different body parts figure into the ability to perform well in a certain sport. Baar explained that a weight of 1.8 kg (4 pounds) added to a runner’s waist will increase the energy used by 3.7%, but if you add that same mass to the runner’s ankle, it increases the amount of energy needed to run by 20%.

“If you have long feet and are wearing a heavy shoe, the energy needed will be much bigger,” said Baar. “So that’s not a good phenotype for running, but if you’re a swimmer, you want to have huge feet, because now you’ve got flippers.”

It is difficult for athletes to overcome an atypical body type at sports’ elite levels. Baar explained that a person who is born without an ideal body for a particular sport can see physical changes from repeated training over long periods of time. For example, Baar described how a person who focuses on swimming can eventually develop a V-shape body ideal for swimming. Those changes might improve performance but may not be enough to make someone elite.

Small differences in body types are more important at the elite level because they can translate to small differences in performance that separate the elites from the also-rans. “Where the body type is going to matter is at the elite level, when you’ve got other people who have all trained exactly the same way as you,” Baar said.

Standing only 5-11, Cody Miller was the shortest swimmer in the 100m breaststroke finals at the 2016 Olympics, but being the shortest swimmer in his event had been the norm for him since high school.

“Quite honestly, it kind of put a little bit of a chip on my shoulder,” Miller said. “I felt like I was lacking in a certain area and so I kind of had to outwork other people.” Miller powered through the last 50m to earn a bronze medal. Several days later, he earned his first Olympic gold medal as the shortest member of the U.S. men’s 4x100 medley relay team, helping Michael Phelps win his last gold medal of his career.

Miller never dwelled on his height, and that attitude likely contributed to his success. Alschuler said athletes with atypical body types who find success at elite levels often do not care that they do not look the part.

“They’re not concerned that being the ‘wrong size’ is going to be the reason that they can’t succeed,” said Alschuler. “They may be aware of it, but they’re not focused on it. They’re not seeing that as a barrier to success.”

Athletes, especially in endurance sports, must develop adaptive strategies. Alschuler said, “If we take the pain or discomfort of completing an event, for example, adaptive strategies tend to focus on a willingness to feel pain, a willingness to experience the pain or discomfort of the activity that you’re doing.” This is one area where someone with an atypical body type can find an advantage over competitors.

However, even that advantage would be slight at the elite level and might not overcome having an atypical body type. “It is easier to make up for size at lower levels, where athletes are more imperfect,” Alschuler said. “The gap narrows at higher levels because athletes at elite levels are optimizing all domains.”

When children start to get serious about a sport and they don’t have the typical body type, is it helpful or harmful to tell them they’re not built for that sport?

Children should have the freedom to choose a sport they enjoy, but there can be risks that someone with an atypical body type for a sport will take unhealthy measures to be the next Khorkina or Bacheler. Encouraging children to select a sport based on body type can be a good thing—so long as they are not being pushed into it—because it can help them avoid unhealthy development, stunted growth and eating disorders, said Baar.

“If you look at weight-class sports, the healthiest people in weight-class sports are the people who are that weight naturally,” Baar said. “Everybody else, those who have to work hard to make that weight, are really suffering.”

“If you just are doing sport for sport and you’re competing for life, it doesn’t matter that your body isn’t perfectly adapted to the sport that you love,” Baar said. “You’re maybe never going to be an Olympian, but that shouldn’t be the deciding factor whether you continue in that sport.”

And who knows? Maybe a tall, gangly girl just traded her basketball shoes for running shoes and someday will tower over her competitors on the track and the podium.

Jeff Burtka is a freelance writer based in metro Detroit. You can read more of his work here.

Related