Judge's ruling upends NCAA, says group can't limit compensation for student athletes

For the second time in five years, the fate of NCAA’s amateurism model landed in the hands of Judge Claudia Wilken. Wilken, the senior district judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, ruled again in favor of the plaintiffs, consistent with her decision in the 2014 Ed O’Bannon case.

For the second time in five years, the fate of NCAA’s amateurism model landed in the hands of Judge Claudia Wilken. Wilken, the senior district judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, ruled again in favor of the plaintiffs, consistent with her decision in the 2014 Ed O’Bannon case.

In the 104-page decision issued March 8, 2019, in Re: National College Athlete Association Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litigation, the judge wrote “allowing each conference and its member schools to provide additional education-related benefits without NCAA caps and prohibitions, as well as academic awards, will help ameliorate their anti-competitive effects and may provide some of the compensation student-athletes would have received absent NCAA’s agreement to restrain trade.”

Neither side is satisfied with the result.

The case, which was filed in 2014 by West Virginia University running back Shawne Alston and former University of California Berkeley basketball player Justine Hartman with co-plaintiffs, stated the previous compensation model often left students hungry and ill-equipped to handle their student roles.

This decision effectively removes limits to the dollar amount colleges can offer to student athletes, but it does not pay students to play ball. Thus, the NCAA’s amateur structure remains intact. In her decision, Wilken wrote any funds provided to the athletes must be specifically tied to education. Tethering dollars to school expenses could protect the ruling from being overturned if and when the NCAA mounts its appeal, as the language falls under the binding law of the Ninth Circuit.

A full review of the recent finding requires a look back at that binding law set in the O’Bannon case, which established current limits. In that case, Wilken ruled the NCAA, by not paying its student-athletes for use of their name, image or likeness (NIL), violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. An appellate court agreed on the NIL issue, but reversed her recommended compensation of up to $5,000 per year for each athlete. Wilken’s new decision incorporated the appellate court’s mandate to tie all compensation to education-related costs. The difference is the list of expenses now can grow exponentially.

Prior to the announced ruling, sports economist Andy Schwarz joined a San Jose Mercury News podcast to discuss what this means for college athletics. In the podcast, Schwarz referred to testimony by Pac-12 Commissioner Larry Scott who claimed a mixed market of paid and non-paid athletes could lead to consumer confusion and harm the image of the NCAA. Both sides will watch the numbers closely to see if there’s a negative impact on fan support. The economist also suggested this ruling could “wake up” the almost identical Jeffrey Kessler-led case which will be heard in the more plaintiff-friendly U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey.

No one knows the how and when all of these changes will take into effect, only that the fight will continue. The ultimate decision may come down to the shifting views of the fan base.

Has the Tide Turned?

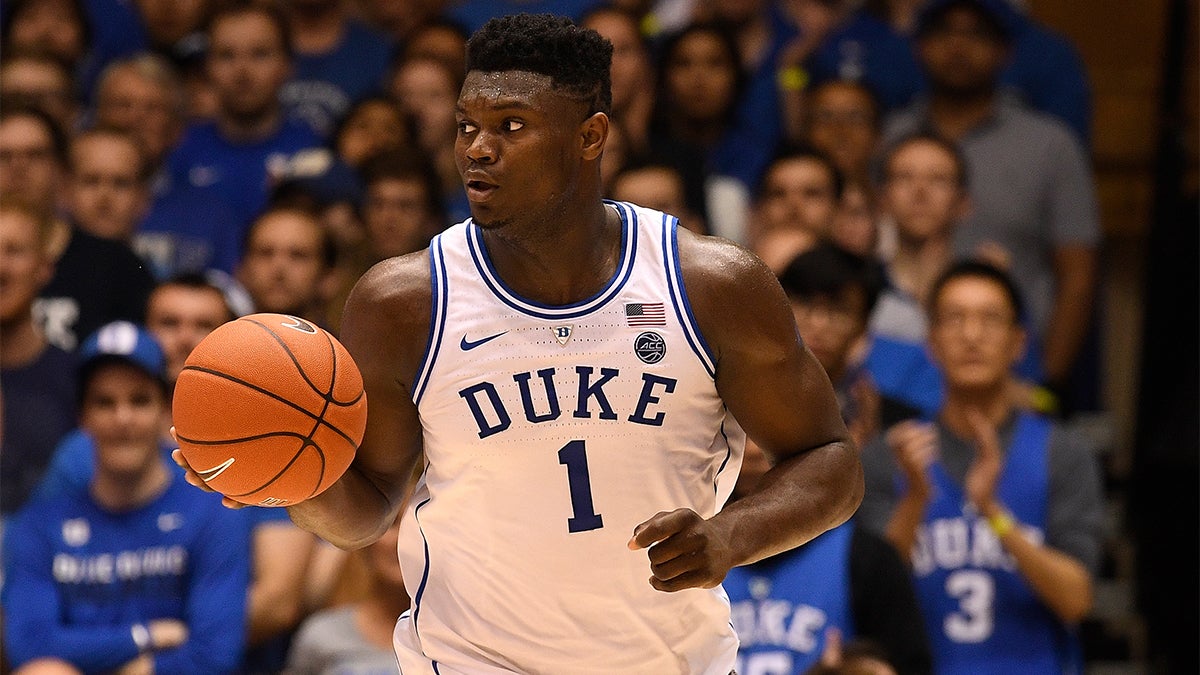

The NCAA, a billion-dollar college sports organization, took a big hit after one very big shoe fell apart with millions watching. In a second, amateurism became a national topic of debate as spectators wondered what would happen if Zion Williamson couldn’t play again. In a New York Times article, experts weighed in on the impact of the moment.

“All this does is put a magnifying glass on an issue that has existed for a long time,” said Gabe Feldman, who directs Tulane’s sports law program, of Williamson’s injury.

No one expects the projected top pick in the 2019 National Basketball Association draft to return to Duke University for a second year; no other No. 1 pick has done so this decade. Since 2010, each first pick played only the requisite single year of college basketball before making the leap to the pros to get paid.

Several current NBA players, such as DeMarcus “Boogie” Cousins, didn’t hold back criticism of the current revenue model, suggesting Zion should sit the remainder of the season and protect his future.

DeMarcus Cousins on the 1-and-done rule: “I don’t understand the point of it. What’s the difference between 18 and 19? Or 17 and 18?” pic.twitter.com/YSB0hL8OJ6

— Anthony Slater (@anthonyVslater) February 21, 2019

Wilken’s ruling could force the hand of the courts again, as her ruling in the O’Bannon v. NCAA did nearly five years ago. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed part of that ruling, stating athletes should not receive compensation in order to ‘preserve the character and quality of the product,’ as decided in the 1984 case of the NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma.

A USA Today article outlined the argument that could make a difference in the fate of her ruling in this case: “The plaintiffs have proposed that limits on athletes’ compensation be set on a conference-by-conference basis, a change that could open the door to athletes being able to capitalize on their names, images and likeness if a conference's schools chose to go that way.”

The Two Sides

Proponents of the current NCAA model argue the 460,000-plus student-athletes competing in 24 sports benefit from invaluable campus and classroom experiences. That’s how they’re paid.

Those arguing against the system consider the swelling increase in revenue a benefit to everyone with a hand in college athletics with the exception of the players themselves. Which side one falls on could be based on the meaning of the label student-athlete.

Pay-for-play for students is a divisive, touchy subject. The Aspen Institute hosted a spirited discussion entitled “Future of College Sports: Reimagining Athlete Pay.” Thought leaders across the spectrum considered what a college system would look like if players could get paid.

What does it mean to pay athletes? Here are three specific ways athletes could receive compensation.

- The Olympic model, based on the current Olympic movement which abandoned amateurism. The model allows for outside income from other entities, including commercials, speaking appearances and autographs.

- Direct pay for performance without restriction by the NCAA would allow students to secure agent representation and negotiate payment or benefits in excess of the cost of attendance.

- Scholarships equaling and not exceeding cost-of-attendance only, which is the current model.

Former athlete and thought leader Kareem Abdul-Jabbar continues to write in favor of pay for college athletes, positing that little has changed in favor of the students since his days at UCLA.

Who added that expensive hyphen in student-athlete?

From 1955-1987, Walter Byers served as the executive director of the NCAA. As such, and as its first full-time employee, he staunchly defended the amateurism business model. He and his legal team decided on the term while defending the league against a lawsuit brought by the widow of an athlete who died after an on-field accident.

Worried the players could be viewed as employees, the NCAA and its legal representatives settled on a strategy that convinced the courts the student status stripped the athletes of standard employee protections.

The Kansas City Sports Commission honored Byers, then 73 years old, at its 1994 Annual Gala Dinner. He surprised many in the audience with his take on the NCAA model.

“Each generation of young persons come along and all they ask is coach give me a chance I can do it, and it’s a disservice to these young people that the management of intercollegiate athletics stays in a place committed to an outmoded code of amateurism,” Byers said. “And I attribute that to, quite frankly, the neo-plantation mentality that exists on the campuses of our country and in the conference offices and in the NCAA.”

In his 1995 memoir titled “Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes,” Byers wrote: “We crafted the term student-athlete, and soon it was embedded in all NCAA rules and interpretations as a mandated substitute for such words as players and athletes. We told college publicists to speak of ‘college teams,’ not football or basketball ‘clubs,’ a word common to the pros.”

A special episode of WBUR’s podcast “Only A Game” explored Byers’ shift from protector of the model to its Gabe remorseful, outspoken critic.

What’s Next?

Even with the ruling, amateurism remains a moving target. Pac-12 Commissioner Scott issued a statement and said the decision “reaffirms the fundamental principles of the collegiate athletic model and of amateurism. … Student-athletes are first and foremost students, who attend college to receive an education and to prepare themselves for success in life, while also pursuing athletic excellence.”

In theory, it sounds noble. Does it pass the test in practice? That’s difficult to determine. In her ruling, Wilken wrote “the rules that permit, limit or forbid student-athlete compensation and benefits do not follow any coherent definition of amateurism.”

To Commissioner Scott’s point, many are confused on the ruling. The actual winner is up for debate even if the plaintiff won on paper.

In a New York Times article on the ruling, the author asked, “how can a judge rule that a law is being broken but allow the lawbreaking to continue?” For greater context, the author goes outlines Tulane University sports law professor Gabe Feldman’s review of the case. “According to Feldman,” says the article, “the answer includes a much-disputed antitrust principle known as the rule of reason. In some cases, including this one, the rule calls for anticompetitive activity to be overturned only if there is a different system that could provide the positive benefits of the anticompetitive system without suppressing other competition as much.”

That gray area leaves room for interpretation as it pertains to the specific role of the student-athlete. When Stanford’s Bryce Love, a running back and top NFL prospect, chose to forgo an in-person athletic appearance at media day during the summer in order to attend class, his student-athlete professionalism was questioned.

Dennis Dodd wrote, “right or wrong, that wouldn't have happened (in the SEC). The need to better himself, the conference and his school would have outstripped another summer school lecture.” Dodd wrote that an athlete making a decision to Skype it in and attend class — being both student and athlete — sets a dangerous precedent, even for an athlete who plans to become a surgeon.

With this new ruling, maybe it would have been permissible for the university to charter a jet for Love’s quick trip to media day as Dodd jokingly suggested.

Mia M. Jackson is a writer based in Germantown, Md.

Related Articles

New basketball league plans to pay student athletes

Opinion: It's time to end the notion of NCAA amateurism

Why this former NBA champion wants to pay college basketball players

How do basketball players go pro in different countries?

Study shows HBCU teams penalized more than others

NCAA report: Men’s college basketball ‘deeply troubled’

News flash: Improper payments to college athletes is #oldnews

Opinion: Let’s stop creating an atmosphere for scandal and pay college athletes

How the FBI investigation into alleged improper payments unfolded