NCAA says amateurism is 'educational' while making millions off student-athletes

Ray Dennison was an Army veteran, father of three and a football player for the Fort Lewis A&M Aggies on scholarship. In September 1955, he shattered the base of his skull on the knee of the ball carrier during a game. He died 30 hours after the incident.

Dennison’s wife, Billie, filed a lawsuit against Fort Lewis A&M for workers compensation. The National Collegiate Athletic Association argued that Dennison was a student-athlete because he was on scholarship, meaning he was not eligible to receive benefits. In its defense, the NCAA avoided terms such as “club,” since that was how professionals referred to their teams. The organization added an amateurism pledge to every scholarship signing.

The NCAA won the case.

Coined by then-NCAA president Walter Byers for that case, the term “student-athlete” is used as a legal precedent to limit the benefits and compensation college athletes can receive while playing full time for the governing body and its institutions.

The NCAA business model focuses on the success of the member schools rather than the athletes who drive the revenue. They avoid compensating student-athletes, do not give them an education comparable to nonathlete students and do not adequately prepare them for post-collegiate life. The NCAA does this all under the rouse that amateurism is the most beneficial thing for these athletes.

Some of the issues the NCAA faces in regard to athletes include:

- Amateurism and eligibility

- Stipends/Compensation

- Academics

“One of the arguments the NCAA makes to protect the status quo is that amateurism is educational and if athletes make money it will hurt their educational outcomes because they will not try as hard in the classroom,” said Victoria Jackson, sports historian and lecturer at Arizona State University and a former collegiate runner.

Katie Ledecky, a former Stanford swimmer, went to the 2016 Summer Olympics. She ended her amateur status in early 2018, enabling her to take advantage of endorsements deals, while still attending school. Receiving money seems to have had no impact on Ledecky’s academic endeavors nor her desire to return to Stanford.

In regard to forgoing her last two years of collegiate eligibility, Ledecky said, “I am... excited about the opportunities and challenges ahead as I continue to compete internationally and further my education.”

Poverty and race

Jackson said the NCAA’s claim carries racial baggage because it is specifically targeted toward football and men’s basketball players, who are predominantly African-American. The minority group makes up 56 percent of Division I men’s basketball players and 48 percent of Division I football players.

Football and men’s basketball are the financial backbone of Division I college athletics. They bring in the biggest crowds and the most revenue. Yet, despite the NCAA grossing more than $970 million in 2017, athletes receive minimal reimbursements for their work. This is especially problematic in the two main sports: 86 percent of African-American college athletes come from families that are below the poverty line, and they need their athletic scholarship to have the opportunity to attend college.

According to research by Dr. Shaun R. Harper, the executive director of the Race and Equity program at the University of Southern California, a consistent divide exists between the graduation rate of African-American student-athletes and all other students. The research also showed African-American male athletes graduate at lower rates than all other African-American men at the university.

However, when these athletes get into the university, usually with more lenient standards, they do not have the same freedoms as other college students. Most collegiate sports teams spend more than 40 hours a week training and practicing, which is equivalent to a full-time job. These athletes have little time for a life outside of athletics. They do not have the time required to get a job. This makes a stipend their only form of income.

Stipends

In 2014, the NCAA gave schools in the Power 5 conferences —Pac-12, Big Ten, Big 12, ACC and SEC —the ability to provide stipends for their athletes. Stipends were conceived to differ by university and cover the “cost of attendance.” They were not mandatory. Prior to the implementation of this rule, some athletes received money through less conventional outlets, such as fake jobs.

This change came about after the University of Connecticut men’s basketball player Shabazz Napier told the media he often went to bed hungry because he did not have enough money for food. Napier made that announcement during the 2014 NCAA Tournament. He said there were times when athletes would be forced to go to bed hungry, due to lack of funds, but they were still expected to play to their full potential.

“These changes weren’t made out of the blue or out of the kindness of the DI directors' hearts,” said Victoria Jackson.

This public display of athlete dissatisfaction with the NCAA’s current structure forced a change to be made after the 2014 season. The Power 5 conferences receive the most publicity and in turn the most NCAA support. Power 5 teams are able to provide their high-revenue sport athletes with the largest cost of attendance stipends. Despite these stipends being higher than at many other universities, these athletes still struggle to make ends meet due to cost of living or their personal situation.

Some athletes are using their stipends to support their families, leaving them with even less. In 2017, Clemson safety Van Smith sent $100 of his $388 monthly stipend home to pay for his little brother to play high school football.

Smith’s teammate, linebacker Dorian O’Daniel, is grateful for the small compensation they receive, but he knows he and his teammates deserve more. “It’s not enough,” O’Daniel told the New York Times. “I know, beggars can’t be choosers, but it’s still not enough. But I’m thankful for what I get.”

Former University of Washington running back Myles Gaskin addressed his issue with the football stipend. “The stipend money is not enough, if you really look into it. It is definitely under the poverty line in Seattle because of the rent... It hurts your pocket to live close to campus… so the money forces you to make (a lot) of decisions. You have to be smart with your money.”

In contrast to the low payments athletes receive, NCAA president Mark Emmert’s salary rose by $500,000 in 2016. For the fiscal year ending in Aug. 2016, he received compensation totaling slightly less than $2 million.

Amateur eligibility based on compensation

Beyond stipends, student-athletes are not allowed to receive compensation for commercial work. Student-athletes, current and past, claim the NCAA is breaking antitrust laws by using players names, images and likenesses in promotional campaigns without proper compensation to these athletes.

If a student-athlete were to accept payment for their participation in commercial work, they would be deemed ineligible by NCAA standards. “In addition to increased educational benefits, I also believe athletes should be able to make money off their NIL (name, image, and likeness), from third parties,” Jackson said.

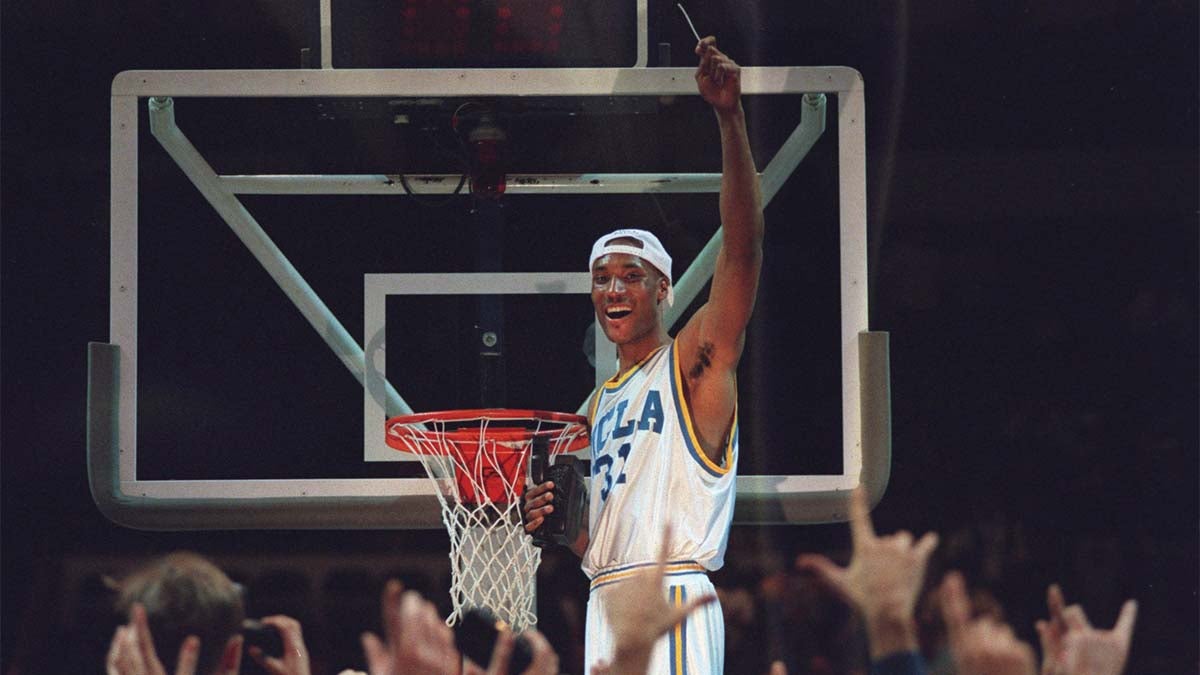

Ed O’Bannon is one of the most notable names in the fight against the NCAA’s amateurism laws. O’Bannon played basketball for UCLA from 1991 to 1995. He was on the Bruins’ 1995 championship team. He filed a lawsuit in 2009.

O’Bannon was a lead plaintiff in the case involving 20 student-athletes from Division I basketball teams or the FBS football division. Electronic Arts created NCAA football and basketball games, using likenesses of real college athletes, but the NCAA did not allow payment to be made to the athletes. O’Bannon argued that the NCAA was restricting trade. This is illegal under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The case was heard in the U.S. District Court for Northern California, in front of Judge Claudia Wilken. O’Bannon argued the NCAA was unjustly using footage of him in television advertisements, and O’Bannon received no compensation for the use of his image. The District Court ruled in favor of O’Bannon and the other plaintiffs. The NCAA appealed the ruling, and had it partly affirmed by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Wilken suggested the NCAA act as the Olympics had regarding allowing professional athletes: Keep stipend-like payments up to $5000 in a trust for the athletes to access post graduation. The Ninth Circuit reversed this ruling.

O’Bannon was able to prove markets exist in college education and group licensing. Wilken ruled schools are able to offer full cost-of-attendance scholarships. Before this ruling, cost of living was not accounted for by scholarships. The NCAA argued such compensation should be determined by licensing and intellectual rights, not on athletic ability. The ruling also stipulated that the reason an athlete leaves the institution before graduation will factor into whether they are entitled to the trust, and that decision would be determined by the NCAA or institution.

As a result of O’Bannon’s partial win, EA Sports removed games featuring college athletes from stores.

The lawsuit carried on for seven years, ending in 2016 when the Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

Jeremy Bloom was an Olympic and World Cup skier as well as a football player for the University of Colorado. During his skiing career, he received endorsement deals and was featured in TV advertisements. Bloom was ruled ineligible to compete for the University of Colorado because he was no longer an amateur.

In 2004, he took the case to court, arguing to remain eligible for NCAA athletics while still collecting his compensation. He claimed the money supported his road to the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics.

The University of Colorado “requested waivers of NCAA rules restricting student-athlete endorsements and media activities” for Jeremy Bloom. The NCAA denied these attempts, claiming amateurism remains a “clear line of demarcation between college athletics and professional sports.”

The court sided with the NCAA, and Bloom returned to professional skiing after being ruled ineligible to compete in the NCAA.

Legal actions against the NCAA continue. On March 8, Judge Claudia Wilken ruled no NCAA caps or prohibitions can be put on a university’s ability to provide their athletes with education-related benefits.

Washington State Rep. Drew Stokesbary is one of the latest to push against the NCAA. Although House Bill 1084, pre-filed in January, is unlikely to pass, it represents a step in the direction of compensating student-athletes.

The bill allows athletes in the state to receive payment for services, such as endorsements or work for the school, up to the fair market value of the services. It would also allow athletes to get an agent. These two concepts are against NCAA rules and would make an athlete ineligible for amateurism status.

House Bill 1084 does not require universities or colleges to pay the athletes a salary. This model will not threaten non-revenue generating sports, while allowing essentially full time athletes to earn money for their work.

More recently, a member of the California State Senate, Nancy Skinner, introduced the “Fair Pay to Play Act.” The legislation is similar to the Washington bill, and, if passed, would give rights to student-athletes. It would make it illegal for any school to restrict rights to be paid for the use of their name, image or likeness.

The NCAA can still name these California student-athletes as ineligible, but the bill is to be used as a push against the independent entity. Without those schools eligible to compete, the NCAA would lose revenue from the 24 public colleges and universities in the state.

The goal of this bill is to push the loss of income for the NCAA against the cost of allowing students to be paid for the use of name, image or likeness, resulting in the NCAA backing down. This could be the first step to a statement against the all-college ruling group in order to gain proper compensation for student-athletes.

Academics

Along with a lack of income, many athletes are leaving school without an adequate education and minimal preparation for life after sports.

Ex-NFL player and Oklahoma State alumni Dexter Manley was illiterate after graduating from a four-year university. When asked to comment, the OSU academic advisor said, “we knew he couldn’t read a textbook... I agree we exploited Dexter for four years, but he exploited us. Coaches further their careers with players like Dexter, and players in turn groom themselves for pro ball.”

Situations such as Dexter’s are not uncommon. Mary Willingham, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, conducted research on 183 athletes at UNC-Chapel Hill in 2012. She found 60 percent of the athletes read at between a fourth and eighth grade reading level and approximately 7 percent read below a third grade level.

Kevin Ross, a former basketball player at Creighton University in the late 1970s, is emblematic of the issues surrounding universities bringing in athletes who are not necessarily academically capable. He had an ACT score of 9 and an SAT of around 800, which is a far cry from the Creighton academic standards. The average admitted students SAT score is 1179 and their ACT score is 27, based on the most recent scoring standards.

While Ross was an athlete at Creighton, he was responsible for nothing academically. He did not have to open a book, do coursework and exams had the answers on it for him. During his senior year, the academic “aid” stopped, and Ross was forced to drop out of Creighton. Ross entered Creighton illiterate and left that way.

The academic experience of these athletes is no accident. Athletic eligibility is the team’s top priority, not the educational experience the players will receive if they are pushed in the classroom, risking lower grades.

Universities changing their academic standards and curriculum to ensure athlete eligibility goes far beyond individual athletes. Numerous cases of academic fraud amongst universities and their athletic departments have been uncovered.

An article in The Sport Journal examined whether revenue sports have a higher likelihood of academic fraud than non-revenue sports. The results showed 73.9 percent of all academic fraud reports are from football and men’s basketball programs.

In 2014, the University of North Carolina was accused of 18 years of academic fraud for offering student-athletes “paper classes.” After an eight-month investigation, Kenneth Wainstein, an attorney, reported at least 3,100 student-athletes took these fake classes to stay eligible.

Syracuse men’s basketball program was caught and sanctioned by the NCAA in 2005 for almost a decade of academic fraud. Head coach Jim Boeheim hired a director of basketball operations to fix the low grades of his athletes. The basketball staff emailed professors through the athlete’s emails, did their coursework and, in one instance, even submitted an assignment to fix a grade from a previous year. Upon being caught by the university and the NCAA, Syracuse was stripped of 109 wins and was banned from playing nine conference games the following year.

Southern Methodist University was put on a three-year probation with no postseason play in 2014 after an employee completed a summer online course for a basketball recruit, enabling him to be eligible for the upcoming season. This was not SMU’s first time running into issues with NCAA regulations. In 1987 the school received the death penalty after it was uncovered that the football team had been paying recruits. SMU is the only school in modern history to be given the death penalty.

And SMU will remain the only school to get the death penalty, even though bigger and more heinous infractions (and, in some cases, crimes) are committed by schools. Why?

Because enacting the death penalty will break the television contracts the schools and conferences have signed. And that would mean less money.

So while the NCAA and its member schools continue to profit off the work of student-athletes, efforts are being made to allow student-athletes to profit off their names, images and likeness, and provide them with a more substantive and well-rounded education. With the push for change coming from government officials, past student-athletes and current student-athletes, the demand for change has reached a peak.

Ellie Simpson is a senior sports journalism student at Arizona State University and Lauren Chaingpradit is a junior sports journalism student at Arizona State University.

Related Articles

NCAA rulings on amateurism called 'absurd,' 'inconsistent'

Opinion: It’s time to end the notion of NCAA amateurism

Opinion: NCAA commission recommendations miss the forest for the trees

NCAA report: Men’s college basketball ‘deeply troubled’

Opinion: Commission recommendations welcome, but face tough road to acceptance