Sport Gives Girls the Space to Define Themselves

Why this matters

Girls benefit from sport in numerous ways, but they may have trouble seeing themselves as athletes. Recent research shows how girls negotiate tensions between femininity and athleticism, for example, as well as how sport helps them develop their identities.

Although female athletes have gained prominence in some arenas, girls still play sports less than boys, and they are more likely to drop out. In a survey of youth between the ages of 7 and 17, the Women’s Sports Foundation’s Keeping Girls in the Game report found that 36.4% of girls and 45.6% of boys played sports, and drop-out rates were 36% for girls and 30% for boys.

Why does this disparity persist? The reasons may include lack of access and perceptions of who belongs in sports.

Research by Arizona State University Assistant Professor Alaina Zanin, supported by ASU’s Global Sport Institute, sheds light on the ways girls internalize and respond to stereotypes and the ways they define themselves. Here are some of the barriers they’re up against.

Girls don’t see themselves as athletes.

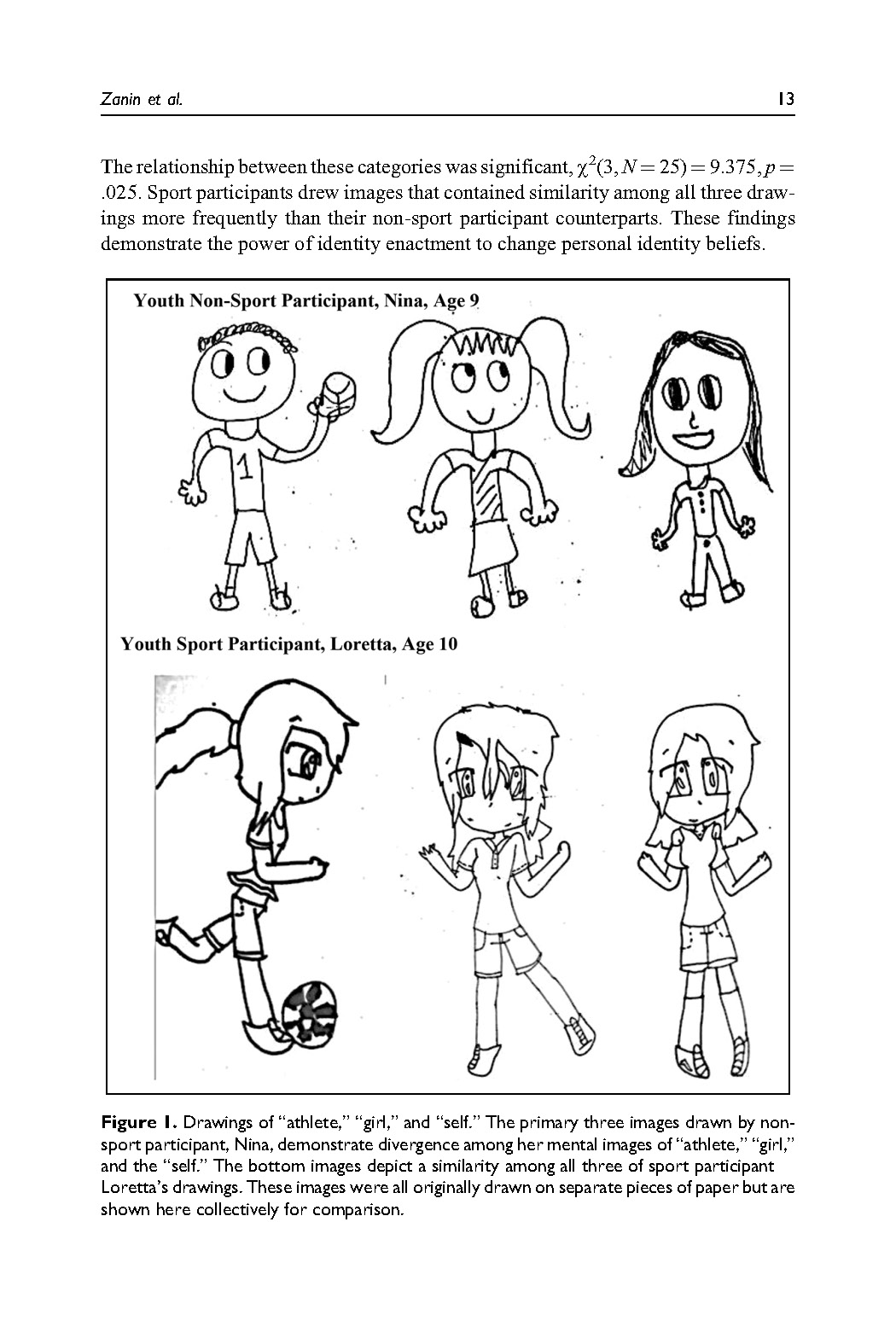

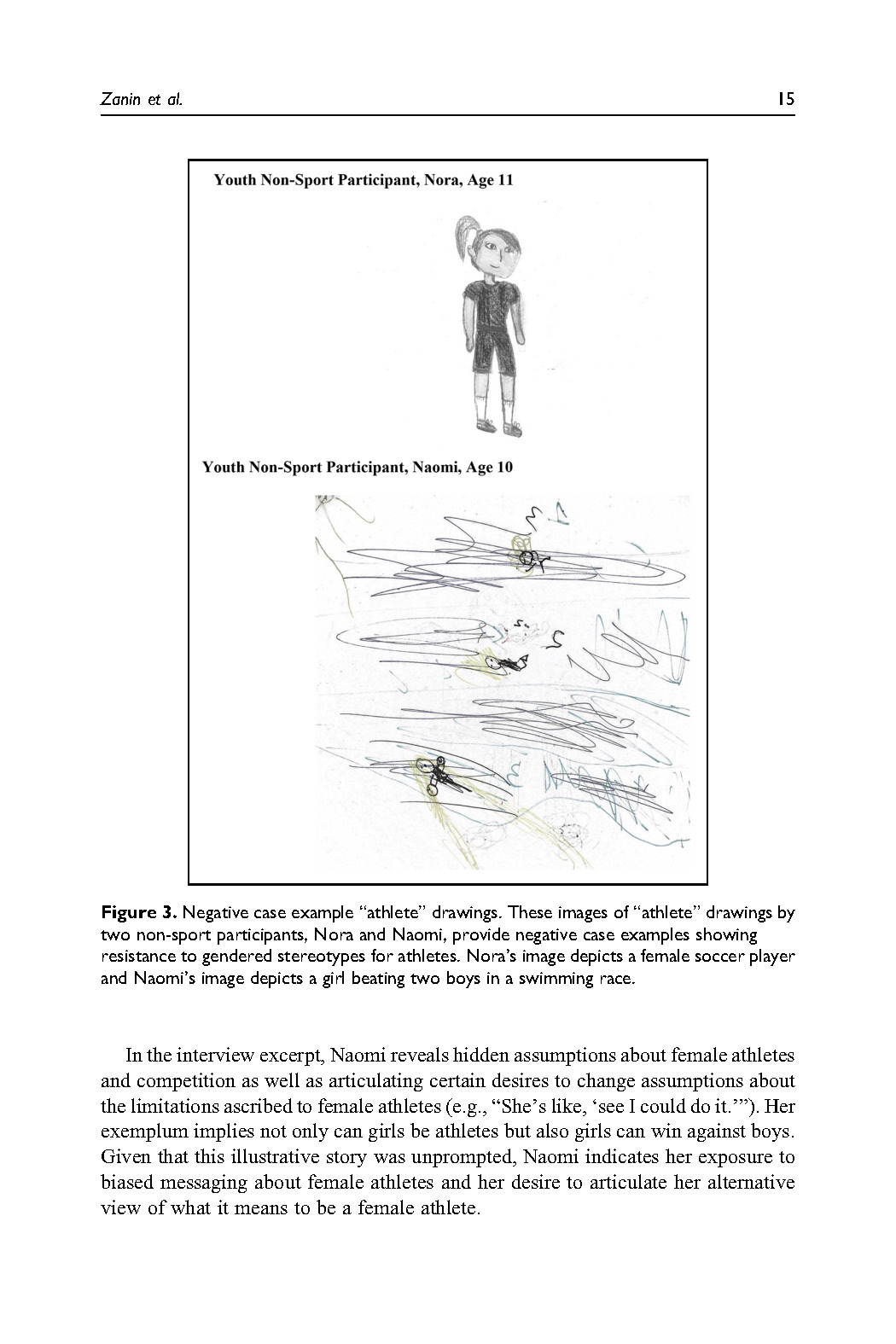

In one 2019 study, Zanin and her team asked girls between the ages of 8 and 12 to draw three images: an athlete; and next, after they finished, a girl; and then themselves.

The study included a group of girls who had recently participated in a sport program and another group of girls who had not participated in sport in the past year. When prompted to draw an athlete, the girls who were not recent participants were more likely to draw a male figure. Some drew a male figure as the athlete, a figure with a dress or skirt and long hair as the girl, and the image of themselves as something closer to the girl than the athlete.

“Girls are not seeing themselves as athletes until they’re able to have those sport experiences,” Zanin said. But, once they engage in the sport, they start to develop identities that include both being a girl and being an athlete, without the two contradicting, she explained.

The study says: “[T]he ability to communicate through the bodily enactment of an athletic identity alters the experience of girls’ feminine bodies. These early exposures to sport extend the range of their embodied experiences and, as a result, alter the range of possible identities for girls.”

Full study published on SAGE Journals.

Gender stereotypes persist.

Girls still receive messages from the media, their peers, their parents, and others that they can’t be both feminine and athletic, Zanin said.

Girls themselves may perpetuate the belief that boys are better suited to sports. A 2020 study that Zanin led included 14- and 15-year-old girls who played club soccer. When asked why they believe more girls drop out of sports than boys, some said girls care more about spending time with friends and on social media than boys do, Zanin said.

Kids also get mixed messages from parents. In the Keeping Girls in the Game report, a third of parents surveyed endorsed the belief that boys are better than girls at sports. Parents of youth who had never played sports were significantly more likely to say that girls were less competitive than boys and that sports are more important to boys than girls.

“Parents are the primary ‘gatekeepers’ of their children’s entry into sport. As such, their attitudes about gender and sport can influence the extent to which they encourage or discourage their child’s participation,” said Karen Issokson-Silver, vice president of research and education at the Women’s Sports Foundation. “When girls lack support from home for playing sports, however that manifests, they are less likely to enter sport, less likely to stick with it if they do play, and therefore less likely to see themselves as athletes.”

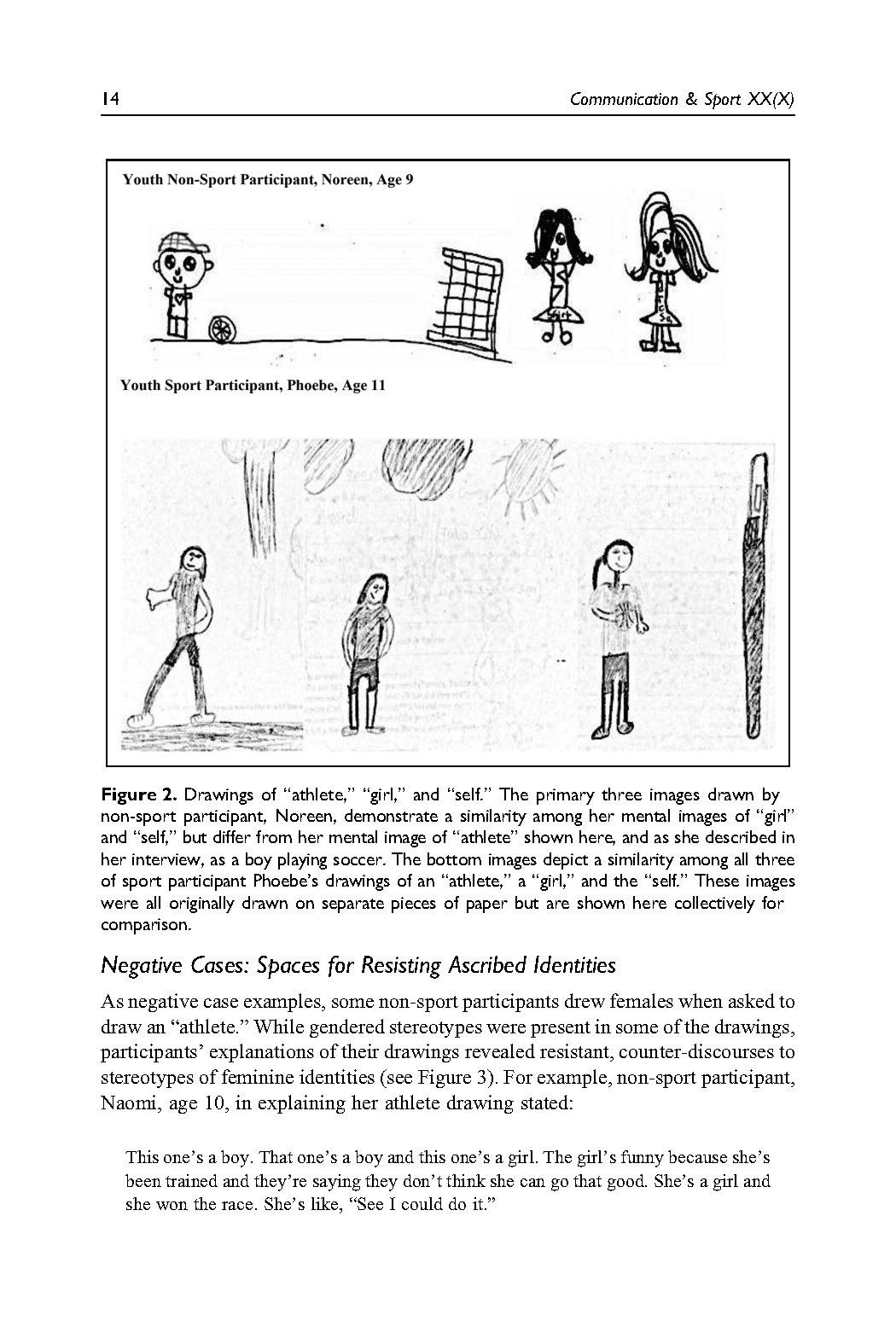

Girls internalize but also challenge stereotypes.

In the drawing study, when one girl drew an athlete, she drew a girl beating two boys in a swimming race. She explained, “The girl’s funny because she’s been trained and they’re saying they don’t think she can go that good. She’s a girl and she won the race. She’s like, ‘See I could do it.’” This explanation shows a tension between the way this girl views female athletes and the way others do. “She managed this tension by presenting a female athlete as the heroine of the story and by ascribing alternative identity characteristics to her,” the study says.

A second study using the same data, published in 2020, looked at how the girls negotiated layered identities. Identities are complex and include layers such as race, class, and gender identity, as well as membership in social groups such as athletic teams.

The study found the girls’ sport experiences expanded their possibilities for what it means to be a girl, Zanin said. For example, if a girl is told that she can’t run fast because she’s a girl, she might respond that she’s a girl and she can run fast. In spreading messages like this, girls are “reframing to themselves and to others what it means to be a girl and what it means to be an athlete,” she explained. “They don’t have to fit into one cookie-cutter version of what it means to be a girl.”

“Girls confront gendered stereotypes in many facets of their lives, and they are continuously challenged. Nevertheless, so many girls are able to push through the boundaries that others set for them,” Issokson-Silver said.

Girls face criticism for being too athletic.

In the study of soccer players, every single girl interviewed had been called a “try hard”—someone who shows off or tries too hard—by male and female peers. They were effectively sanctioning each other for excelling. These girls responded in different ways, including concealing their effort, rejecting the label, and embracing the “try hard” identity.

“It’s really problematic, because when you sanction a girl’s effort toward excellence, you’re just trying to maintain mediocrity for everyone else, and it’s really holding girls back,” Zanin said. “They should be able to be excellent and to beat the boys in gym class and not feel bad about it.”

Although these girls’ athletic abilities had been diminished, the researchers found that their sport participation supports a growth mindset—that you can develop talent through effort, Zanin said. So when these girls were criticized for their effort, “they were mostly able to respond in ways that protected their identity, and also kind of rejected this underlying idea that effort is not a good thing,” she said.

The study concluded: “Using effort-based praise (e.g. ‘Wow! You ran so fast, you must have trained really hard’) rather than outcome-based praise (e.g. ‘You’re the fastest in the class, you must be a natural’) could equip female adolescents with the necessary language to reject or embrace a ‘try hard’ identity.”

A path forward.

In the drawing study, all the participants said they would like to participate in some form of sport in the future. Even the girls who drew male figures as athletes saw sport as something they wanted to take part in.

The study suggests that providing more opportunities for youth sport, recruiting more female coaches, and building support systems would allow more girls to participate.

Increasing access. For many kids, structural barriers get in the way of their participation—including transportation and cost. If girls can’t get past these barriers, their ability to see themselves as athletes doesn’t matter much.

“We need to make it easy for girls to participate,” Zanin said. Having fewer cut sports and more recreational options to try out different sports can help, especially in underserved communities, she said.

“Girls who have access to more sport resources (i.e., availability of community and/or school-based sport programs, family resources to pay for entry, equipment, transportation) may have a different experience navigating gendered stereotypes because they are experiencing the joy and benefit of sport for themselves,” Issokson-Silver noted.

Since COVID-19 shut down sport programs, opportunities for girls to participate as programs open up again may be even more important now. “Some of the students don’t have any support at home,” Zanin said. “These kids need other adults in their lives that are cheering them on.”

More female coaches. In the drawing study, some girls mentioned specific people—including parents, friends, coaches, and famous athletes—in explaining their drawings. This suggests that exposure to role models in sport expands girls’ possibilities to define their identities.

In 2019, only 24% of youth sports coaches were female, down from 28% in 2014, according to the Aspen Institute Project Play’s State of Play 2020 report.

“There is no question that when girls see and have experiences with female coaches and female athletes, they are better able to imagine their own success in sport. They see that they belong,” Issokson-Silver said.

To empower young women to be coaches and role models, Zanin and two other professors developed an internship course for youth coaches at ASU, supported by a seed grant from the Global Sport Institute. The students spend four weeks in the classroom and then coach a girls’ sport program in an underserved community. The pandemic delayed the course, which is now scheduled to start in 2022.

The benefits of sports are numerous. Among them are that girls who play sports are more likely to be leaders, more likely to finish high school, and less likely to engage in risky behaviors, Zanin said. “My argument is that if girls can develop identities as empowered female athletes, they are going to be resilient in the face of other challenges and setbacks.”

Allison Torres Burtka is a freelance writer and editor in metro Detroit. You can read more of her work here.

Monthly Issue

The Power of Women & Girls in Sport

From participation to coaching, and shattering leadership ceilings, 2020 was slated to be a year of progress for women’s sport. But then came the pandemic.

2021 could still stand to be a significant year of growth for women and girls in sport. What long-standing barriers and future opportunities lie ahead?