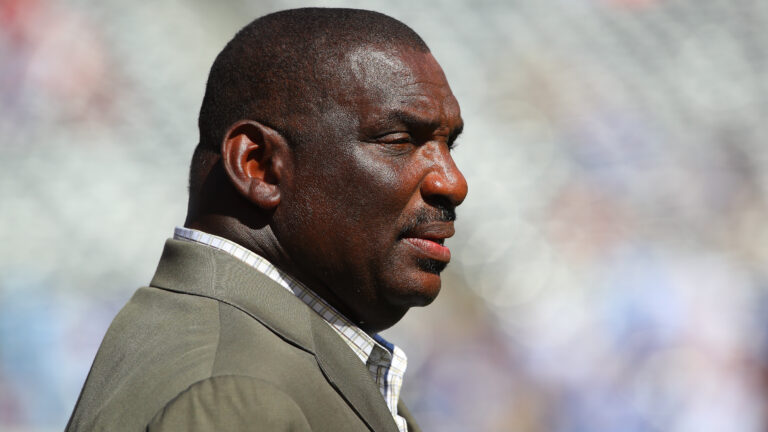

The Enormous Gap Left By John Thompson

Why this matters

With the passing of John Thompson, his legacy will live on, but will there be more Black coaches like him in college sport?

The Sports world lost a titan of the industry early this month with the passing of John Thompson Jr. at age 78.

At 6 foot 10 and more than 260 pounds, Thompson, was a mountain of a man in stature and impact. He spoke with the moral authority of a black man who triumphed over racism and made creating opportunities for other African Americans his crusade.

Who among today’s black coaches has that authority?

The larger question is will there ever be another John Thompson-like figure, a person willing to sacrifice to move mountains.

I put the question to Tommy Amaker, the headmen’s basketball coach at Harvard.

Amaker is on the Board of Directors of the National Association of Basketball Coaches and co-chairs the newly created committee on racial reconciliation.

“There have been a lot of smart people, but very few have been wise,” Amaker told me during a recent interview. “There have been a lot of respected people, but very few have ever been revered. There have been many people who have had success, but very few have ever truly been significant. Coach Thompson was wise, he was revered and he was significant. So my answer is "No, there will never be another John Thompson."

During the 1980s and early ’90s, Thompson along with John Cheney George Raveling and Nolan Richardson was among the first wave of black coaches to have influence.

The source of that influence was their ability to recruit highly talented, blue-chip black players. Their ability to recruit and be successful with these players prompted white athletics directors, for a time, to hire more black coaches with the idea that they would recruit more blue-chip Black players.

Chaney, 88, coached at Temple between 1982 and 2006; Raveling coached at Washington State, Iowa and USC between 1972 and 1994; Nolan Richardson, 78, coached at Tulsa and Arkansas, between 1980 and 2002. Richardson won a national title in 1994. Thompson, who coached at Georgetown from 1972 to 1999, won a national title in 1984 and played for the title three times.

All four coaches are in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

In their era, the priority became pushing back against measures that denied opportunity for Black athletes. This issue galvanized black and white coaches.

In 1989, Thompson walked off the court before a game to protest an NCAA rule that denied athletic scholarships to freshmen who failed to qualify for athletic eligibility under the academic standards of Proposition 42.

Before that legislation, players could have a scholarship but could not play as freshmen. Thompson and other coaches argued that the new legislation would have a disproportionally negative impact on Black athletes.

The NCAA backed off in the face of implied threats that teams might boycott the NCAA’s cash cow—the basketball tournament. What initiative can galvanize black and white coaches in 2020?

In this era of Black Lives matter, the galvanizing issue should be black advancement.

The daunting obstacle facing African Americans in the field of sport and play is securing positions as head coaches and athletics directors, especially at Power 5 schools.

Why is securing a foothold at the Power five-level so important? “Because those are the ones that get the most attention and the exposure and the more likely opportunities to be on that national stage,” Amaker said.

Black athletes have dominated major basketball and football since the 1980s. Yet that talent pool has not yielded anything close to commensurate black power at leadership positions in either football or basketball. African American men and women continue to face a granite wall of resistance.

There are no African American head basketball coaches in the Pac-12.

Juwan Howard is the only black men’s head basketball coach in the Big Ten. The SEC has two.

On the positive side, half the coaches in the Big East are black.

College football has equally dismal numbers. There are three black head coaches in the 14-team Big Ten. There is one head coach of color in the 14-team Southeastern Conference, one in the 14-team Atlantic Coast Conference, none in the 10-school Big 12.

The Pac-12 has the greatest head coaching diversity of any conference, with African Americans holding five of 12 positions.

In the next highest tier, the Group of Five, three of 65 head coaches are African-American. There are no black head coaches in the American Athletic Conference or the Sun Belt.

The issue confronting aspiring Black head coaching candidates has haunted them for years.

- Blacks head coaches generally get a shorter period to prove their coaching skills.

- They often find it more difficult getting a second chance once they are fired from their first job.

- Black coaches rarely get a chance to shine at the most prominent schools.

Who among the new legions of black coaches has the weight, the stature, and the appetite to break down the granite wall?

Leonard Hamilton, 72, is in his 18th season at Florida State and has been a head coach at Oklahoma State and Miami.

Tubby Smith 69, who won the national title at Kentucky in 1998, is in his fourth season at Memphis.

Amaker, 55, who has been a head coach at coached at Seton Hall, Michigan, and now Harvard.

Big Ten-commissioner Kevin Warren, 56, is the first and only African American commissioner of a Power 5 conference.

The challenge for the new wave of black coaches and administrators is how to put African Americans in leadership positions in Power 5 conferences in leadership roles.

If progress is to be made influential, white coaches must lend their muscle to the cause. Amaker is confident that this will happen.

He is involved in a new initiative started by John Calipari, the Kentucky men’s head basketball coach. The John McLendon Minority Leadership Initiative is designed to get more minorities in leadership positions within the NCAA by creating internships, especially at Power Five schools.

McClendon, the legendary Johnny Mac, is recognized as the first African American basketball coach at a predominantly white university and the first African and the first African American head coach in any professional sport.

“We’ve got to get more minorities, black candidates and black people in the pipeline to be athletic directors,” Anaker said. He noted that more than 80 coaches in football and basketball are involved in the initiative. They include some of the nation’s most powerful coaches, like Calipari and Duke's Mike Krzyzewski. In football, Clemson’s Dabo Swini and Alabama’s Nick Saban are involved. Those coaches have to intervene and break the good ol boy’s network and insist that black candidates get an opportunity.

“Everybody is seeing this as a huge opportunity for us to have our athletic departments become a training ground,” Amaker said. “Hopefully we’ll be able to hire some of these individuals who want to stay involved in this and become athletic directors, deputy ADs, assistant Ads. We think that's another way of us helping become more diverse.”

Outside of a moral imperative by presidents and athletic directors to hire black coaches, the real leverage rests with young athletes who provide the backbone of big-time, revenue-producing sports programs.

In an ideal world, young highly recruited black athletes and their families would pay more attention to who is in charge of these programs and base their selections on that. The encouraging news is that former NBA players have gotten college jobs: Howard at Michigan, Stackhouse, Vanderbilt, and Mo Williams is the head coach at Alabama State.

For all of the good intentions and spirit of cooperation, there is no progress without struggle. Thompson spoke his mind and was more concerned with creating opportunities than making friends.

Now more than ever, we need the moral force and conviction that Thompson represented.

William C. Rhoden, the former award-winning sports columnist for The New York Times and author of “Forty Million Dollar Slaves,” is a writer-at-large for The Undefeated.

Monthly Issue

The Reset of College Sport

Sport at the college level in America is facing issues reflective of the world at large. From the calls for racial equality, labor disputes and discussions, to health and safety concerns with playing in a pandemic - what will this reset moment look like?