Dartmouth hiring Callie Brownson shows growth of women in football roles

From the year the Declaration of Independence was written, 144 years passed before female citizens in the United States were granted the right to vote.

The Equal Pay Act became law in 1963, but most women in the workplace will bet their salaries against their male counterparts’ that equal pay for equal work remains more aspirational wording than legal tender.

In 1973, 53 years after women were given the right to vote, the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade allowed women the right to control their reproductive choices.

And nearly four decades ago, the Equal Rights Amendment fell three states short of being ratified. The effort has remained in limbo since the amendment’s deadline passed in March 1979.

Starting with the phrase “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence, women’s rights have been mostly wrong in the good ol’ U.S. of A.

While it is hardly a compelling issue compared with the examples cited above, women seeking to break into a male-dominated sport such as football see progress as glacial and begrudging. Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are achievable as long as it doesn’t mean a coaching or administrative job.

Changes are afoot, however. Dartmouth coach Buddy Teevens, who has been an innovator in football concussion prevention, brought in two women as interns during the Big Green’s preseason practices.

“There’s no reason it has to be a male-only profession, but it’s been that way historically. Things change slowly,” he said. “Our not tackling in practice to limit head injuries — people said I was an idiot, that it’s ‘not football.’

“The sport has been a male bastion. But times are changing. The bottom line is that women involved in football can be very productive. It’s half the population who aren’t being considered. They’re smart, driven and have a passion for the game. I think there are more options available, in either administrating or coaching, and, hopefully, those options are increasing.”

Teevens acted on his words on Sept. 11 when he hired Callie Brownson as Dartmouth’s offensive quality control coach. She is thought to be the first female hired as a full-time coach at the Division I level. Brownson and Chenell "Soho" Tillman-Brooks were the two interns at Dartmouth.

“Callie is a coach who happens to be a female as opposed to a woman who is trying to coach,” Teevens said in a news release. “That distinction became very apparent to my players and coaches. We've hired a coach who will better our football program."

About two dozen women are working as on-campus recruiting coordinators at Football Bowl Subdivision schools. Bedlam rivals Oklahoma (Annie Hanson) and Oklahoma State (Patsy Armstrong) each made hires during the offseason.

[beauty_quote quote='"The bottom line is that women involved in football can be very productive. It’s half the population who aren’t being considered. They’re smart, driven and have a passion for the game. I think there are more options available, in either administrating or coaching, and, hopefully, those options are increasing." - Dartmouth football coach Buddy Teevans ']

Hanson spent last season at North Carolina in the same role. Second-year Sooners coach Lincoln Riley, who had come to Norman from East Carolina, had heard of Hanson’s work with the Tar Heels and believed she could help boost OU’s recruiting.

“It wasn’t a male/female thing,” Riley said. “It was about hiring the best person for the job. She has a really good skill set, and she was the first person I thought of. She’s been through the fire of being an athlete, the competition. She understands the commitment, how competitive it is. You kind of get all in one with her. She’s bringing fresh new ideas and helping us push the envelope recruiting-wise.”

Oklahoma State coach Mike Gundy hired Armstrong from a similar position at San Diego State, and his reasoning echoed Riley’s: She was the most qualified person for the job.

“In certain situations, in the recruiting process, a female is more valuable and can have a bigger impact than a male,” Gundy said. “We need females on our staff. They see and hear things differently.”

Comments like those tread close to the woman’s touch or token female hiring philosophy. Armstrong counters that thinking.

“Women can relate to the mothers of the sons that we’re recruiting,” Armstrong said. “The details required for the on-campus recruiting involves a unique skill set. I think a few years ago, the people in these positions might have been former coaches or guys who wanted to get into coaching. They might have not been as well-versed in handling those details and might not have the skills to relate to the families. I think that’s why there’s been a trend to hire women for this operations/ logistics type role. I’m not trying to be a coach.”

When high school recruits make either official visits (limited in number by the NCAA and paid for by the school) or unofficial visits (unlimited in number and the recruit pays his expenses), the recruiting coordinator wants the experience to be perfect. From meeting with coaches to arranging campus tours to mingling with the school’s student-athletes to meals to any perks that don’t violate the rule book, the job requires precise planning.

[beauty_quote quote='"We need females on our staff. They see and hear things differently.” - Oklahoma State football coach Mike Gundy ']

“I think women might be a little more creative and have an eye for what might appeal to the moms and the families,” said Makenzie Franklin, the director of on-campus recruiting at UCF after previously filling the same role at Tennessee. “The staff here has been receptive to having a woman’s perspective and opinion. I think it balances out the staff and makes it more well-rounded. I’ll think of things that the men might not and vice versa.”

According to the Tulsa World, 38 women work as athletic directors in all three NCAA divisions. Seven work at the Division I level. Both Armstrong and Franklin believe experience as a football recruiting coordinator at a Power Five school is another step up the ladder to bigger administrator jobs.

The women’s movement has reached pro football. Samantha Rapoport, the NFL’s executive director of football development, created the NFL Women's Careers in Football Forum in 2017. Earlier this year, the second forum focused on women who are seeking careers in football operations and need help in making contacts for that first job.

"Not only are we trying to inspire women to apply and create this opportunity for them, but we're really challenging them to get their resumes on the [appropriate person's] desk because people can't hire women or minorities if they're not getting their resumes," Rapoport said.

Women making strides in college sports administration is on a parallel track with women who seek roles on the field as coaches.

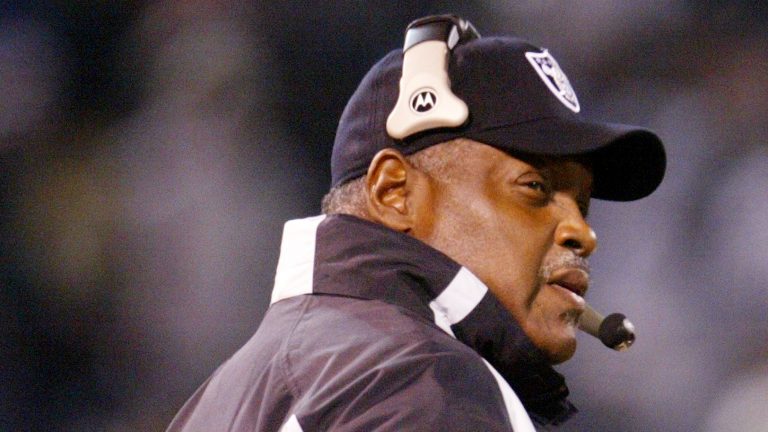

In 2015, Jen Welter was an intern on the Arizona Cardinals staff. In 2016, Buffalo hired Kathryn Smith and last season San Francisco hired Katie Sowers as full-time assistants. Kelsey Martinez is in her first season as strength and conditioning coach with the Oakland Raiders. In the college ranks, Sue Lizotte is a graduate assistant at Bryant University, a Football Championship Subdivision school in the Northeast Conference.

If cracks are showing in the glass ceiling separating women from administration jobs, on-field coaching opportunities in the macho world of football are secured behind bulletproof glass. Again, though, there are signs of progress and change.

Brownson and Tillman-Brooks were invited by Teevens to be Dartmouth “quality control coaches,” which in the Ivy League are the equivalent of graduate assistant coaches in the FBS level. It was an all-they-could-learn buffet. They were exposed to every part of the program: acclimating new players, strength and conditioning, recruiting evaluations, film breakdown and practice schedules.

“There were no limitations on what we were involved with,” said Tillman-Brooks, who has been coaching at various levels for 15 years. “The players were open-minded and welcoming. It was a real opportunity, and it was about inclusion. They treated us as coaches.”

Teevens described the two women as “grinders.”

“That’s the highest compliment you can pay to anyone involved with coaching football,” he said. “We looked at it as a win-win situation. They both showed up and jumped in with both feet. They’re coaches. They’re good coaches, knowledgeable coaches. They just happen to be women. They were one of us. If you’re passionate about the sport and can handle the long hours, it doesn’t matter. There are a lot of guys coaching in the NFL who didn’t play college football. Women can do the same thing.”

Whether as on-campus recruiting coordinators or through seeking opportunities to coach football, advancement and opportunity involve combinations of networking, hard work and opportunity.

[beauty_quote quote='“There were no limitations on what we were involved with. The players were open-minded and welcoming. It was a real opportunity, and it was about inclusion. They treated us as coaches.” - Dartmouth coaching intern Chenell Tillman-Brooks ']

“I look at it like, ‘Patsy, this isn’t just about you,’” said Armstrong, who is the first woman to work for the Oklahoma State football program. “It’s bigger than just me. I want to make sure I set the tone for myself, for women, for African-American women.”

The Manning Passing Academy has been held the past 23 years in Thibodaux, La. The Manning family – Archie, Peyton, Eli and Cooper – started the camp to bring together high school and college quarterbacks for a week of drills and coaching. This year, for the first time, the MPA added a two-day camp for girls age 8 through 12. Tillman-Brooks and Brownson coached at the camp, which is where they met Teevens. That led to the opportunity to spend time on the Dartmouth staff.

When Brownson got the phone call inviting her to the inaugural MPA for girls, she jokes she didn’t believe her ears and thought she was in a bad cell coverage area. Her initial conversation with Teevens in Thibodaux was about networking and not job hunting. The time spent in Hanover, N.H., was master-class learning.

“It was a crash course, like taking a 16-week class in half the time,” said Brownson, who last year interned in the New York Jets’ personnel department. “The young men on the Dartmouth team were phenomenal in the way they welcomed us. They listened to us and treated us like the other coaches. We were coaches helping the team, not female coaches. It was a great opportunity for coach Soho and me, and I think it shows that the future is bright.

“We’re trying to change the norm, the dialogue. When I hear that women don’t know football or don’t belong in football, that motivates me more to change that conversation and those attitudes.”

Abby Falcon, 10, of Houma, La., participated in the Manning girls camp. Her generation might continue the current progress and evolution.

“I hope girls are not afraid to join football because they can go and do it,” she said. “Even though people will say ‘You can’t do it,’ they will do it. I hope that when I grow up people won’t discourage girls from playing football and it will just be an everyday thing.”

Wendell Barnhouse started his career as a sportswriter at 18 and spent the next four decades in newspapers writing and editing. From 2008-2015 he was the website correspondent for the Big 12 Conference producing written and video content. He has spent the last three years freelancing, most recently covering college basketball for The Athletic.