Non-profit colleges bringing in 'Fortune 500' revenues through athletics

This is the time of the collegiate sports season when conferences hold annual meetings to wrap up the August-to-June calendar of competition. The so-called “Power Five” leagues have announced how much revenue was produced for the 2016-17 fiscal year with most of the money being distributed to each member school.

The revenue generated for the 2016-17 fiscal year by the Atlantic Coast, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and Southeastern conferences added up to approximately $2.2 billion from their sports revenue streams. None of the conferences share similar reporting methods but they can’t restrain from bragging about their cash flow … nor can they hide from the eventual media reporting culled from tax filings.

Power 5 conferences' combined annual revenues, per tax records:

FY17: $2.46 billion

FY16: $2.3 billion

FY15: $2.1 billion

FY14: $1.57 billion— Steve Berkowitz (@ByBerkowitz) May 25, 2018

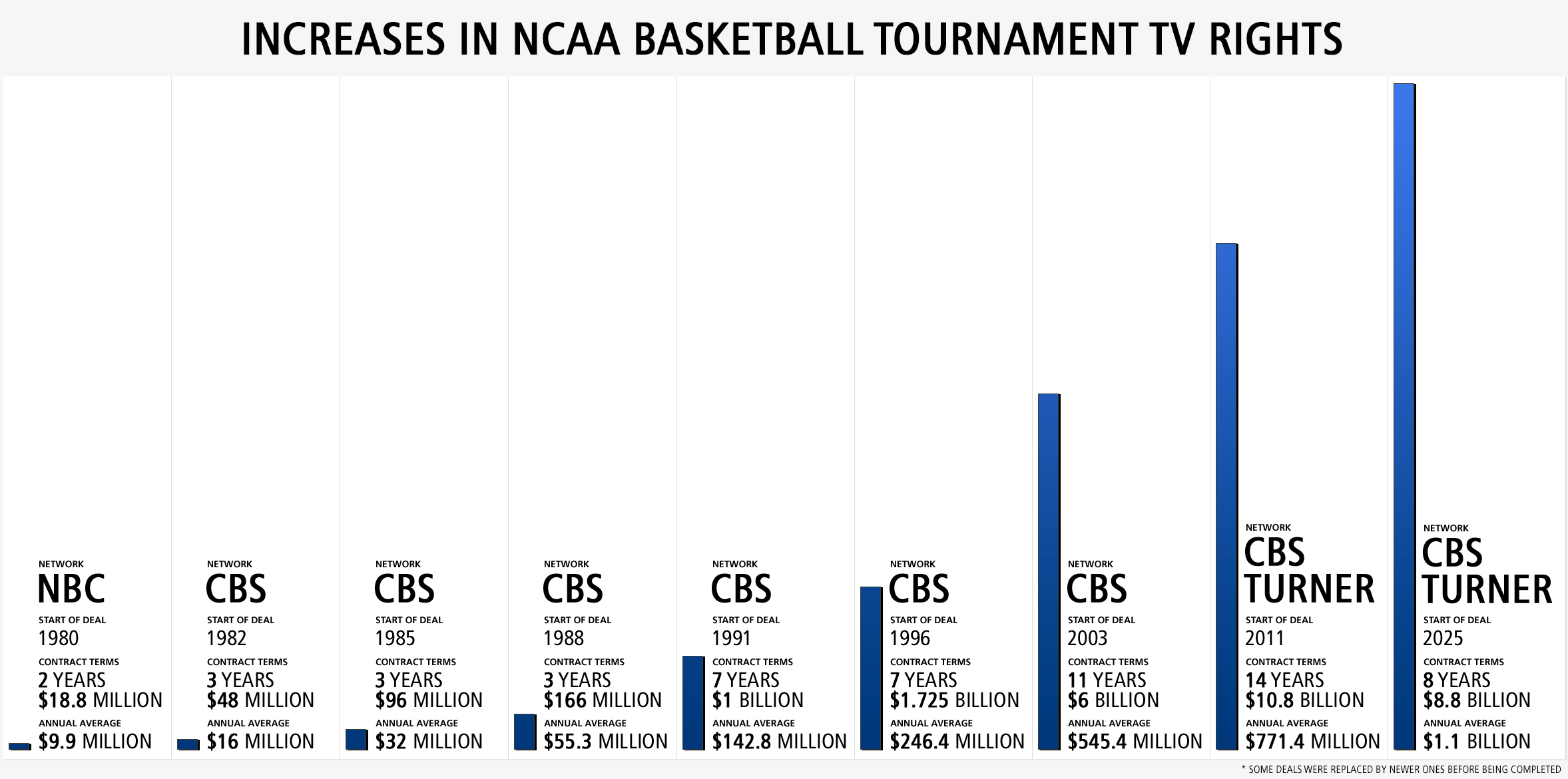

The per-school revenue-sharing checks range from around $30 million to $40 million. The money comes from the conferences’ lucrative television deals (the Big Ten, the SEC and the Pac-12 each have revenue-generating networks), bowl payouts and money based on success in the NCAA Tournament.

Two billion – with a “b” – dollars for 64 Power Five schools. And that $2 billion might be conservative. The Washington Post dug into financial records of 48 of the Power Five schools and found their athletic department income at those schools had, from 2004 to 2014, jumped from $2.67 billion to $4.49 billion.

No matter the accounting method or the bottom line, that’s not bad for the NCAA and member schools that have been classified as nonprofits free of paying taxes. Plus, college sports has managed to create a combination that defies economics – one part capitalism, one part socialism.

“I can’t think of another nonprofit business or industry that brings in a comparable amount of money as the NCAA and college sports does,” said Andy Schwarz, an antitrust economist with a subspecialty in sports economics. “The bigger nonprofits usually exist for the greater good, providing some sort of service. Just because it has a nonprofit status doesn’t mean (college sports) is a selfless charity – it’s a selfish charity.”

As Nick Greene wrote recently for Slate.com: “It’s a pretty sweet deal for the NCAA and its associated conferences, which generate Fortune 500-type revenues from something produced, gratis, by unpaid amateurs. Not paying taxes is a nice cherry on top of that lucrative sundae …”

But with all this income, the “out go” matches it. Athletic departments, especially in the Power Five conferences, make money to spend money. The goal is a zero-sum budget. There is no saving for a rainy day.

“It would be tough to make all this money and not spend it because then they couldn’t cry poverty and say there is no money to provide to the labor force (student-athletes),” said David Ridpath, associate professor of sports administration and president of the Drake Group. “They spend it on coaches salaries and facility upgrades that often aren’t necessary.”

Auburn spent nearly $14 million to install one of the largest score/video boards in college football; it’s glow could be seen at night 30 miles away. (At the time, the school’s athletic department was $17 million in debt.) Texas refurbished its locker room with more than 100 state-of-the-art lockers that cost nearly $9,000 each. Clemson spent $55 million for its football operations center that includes a 9-hole mini-golf course, laser tag, movie theater, bowling lanes and barber shop.

The quest to match or top other schools – in particular, rivals – has led to a facilities race that rivals the Cold War arms race. While perhaps a dozen football programs and perhaps twice as many college basketball programs have legitimate national championship aspirations, most Power Five schools must settle for lower goals – reaching bowl games or qualifying for the 64-team NCAA Tournament.

At the end of June, Bob Kustra will step down after 15 years as Boise State’s president. The school in Idaho has enjoyed a special place as one of the top football programs in the Group of Five – those five conferences that compete in the Football Bowl Subdivision for football but whose members aren’t flush with cash like those schools in the Power Five conferences.

“The keeping up with the Joneses idea has been a concern that I've had since I've been president here,” he said. “There was always this push to keep up, especially coaches salaries, which I think are ridiculous and out of control. I’m paying our football coach (Brian Harsin) more than he’s worth. But so is every other school out there. There’s an unrelenting pressure to keep up.”

Kustra admits the fame that came with three victories in the Fiesta Bowl and the football program’s consistent success helped spread Boise State’s brand and “allowed us to build out the rest of the university.” But Boise State is a rare example of a university that basically caught lightning in a bottle.

Here are some examples of what it’s like in college sports’ high-rent district:

- In 2005, the total revenue for the Power Five conferences – which at that time had significantly different membership than they do today – was $570 million. By 2020, that total revenue is projected to hit $2.8 billion – an increase of 391 percent in 15 years.

- Six coaches at FBS schools will make more than $7 million per season in 2018. Alabama coach Nick Saban, according to data compiled by USA Today, has an annual salary (total compensation) of $11 million.

- Defending national champion Alabama recently announced its 10 football assistant coaches will receive $5.9 million in total salary this season. Scott Cochran, the team’s strength and conditioning coach, has received a $50,000 raise. He’ll earn $585,000 this season.

- According to a survey conducted by AthleticDirectorU.com, the average salary for athletic directors at the 65 Power Five schools is slightly more than $937,000. And 15 of those athletic directors are making more than $1 million in yearly salary, topped by Notre Dame’s Jack Swarbrick at slightly more than $3 million.

- In its financial report to the NCAA for fiscal year 2017, Texas became the first school with its athletic department to have at least $200 million in both operating revenues ($215 million) and expenses ($207 million) in the same year.

On the Monopoly board, low-rent Baltic Avenue is just around the corner from Park Place. There are numerous examples of schools running faster and faster to keep up only to find themselves falling deeper and deeper into debt.

- The Kansas football program, which has endured a decade of mediocrity in the Big 12 Conference, has seen a loss of $6 million in ticket sales over the last 10 years. While the success of the school’s basketball program has helped offset the overall financial loss to the athletic department, propping up the football program has led to a $300 million fundraising project to upgrade the football stadium in hopes that will help attendance for a team that is 3-33 over the last three seasons.

- Cal-Berkeley sponsors 30 sports programs and most depend on revenue generated from football and men’s basketball. But the other 28 sports have been put in jeopardy because the athletic department has been losing money – a reported $14 million last year. The school recently agreed to assume $400 million of the athletic department’s debt. Earlier this decade, Cal embarked on controversial stadium renovations that cost $321 million (plus $153 million for a student-athlete high performance center). That led to most of the current debt.

- Both Division I universities in New Mexico have debt-ridden athletic departments. The University of New Mexico athletic department is $4.7 million in debt to the school and might have to cut some of its 22 sponsored sports. New Mexico State’s athletic department budget of $18 million is nearly half that of UNM’s but NMSU athletics still has slightly more than $4 million debt to the school. New Mexico is in the Mountain West Conference – one of the Group of Five leagues – while New Mexico State will return to being a football independent in 2018. Neither school benefits from the lucrative revenue streams the Power Five schools do.

Ridpath was interviewed four years ago by the Washington Post for its deep dive on college sports budgets at the Power Five level.

Ridpath was interviewed four years ago by the Washington Post for its deep dive on college sports budgets at the Power Five level.

“College sports is big business, and it’s a very poorly run big business,” he said then. “It’s frustrating to see universities, especially public ones, pleading poverty … and it is morally wrong for schools bringing in millions extra on athletics to continue to charge students and academics to support programs that, with a little bit of fiscal sense, could turn profits or at least break even.

“The current model does not work. Someday it will implode.”

Wendell Barnhouse started his career as a sportswriter at 18 and spent the next four decades in newspapers writing and editing. From 2008-2015 he was the website correspondent for the Big 12 Conference producing written and video content. He has spent the last three years freelancing, most recently covering college basketball for The Athletic.

Related Articles

NCAA rulings on amateurism 'absurd,' 'inconsistent'

Opinion: It's time to end the notion of NCAA amateurism