Linsanity aside, Asian, Hispanic athletes face uphill battle getting recruited

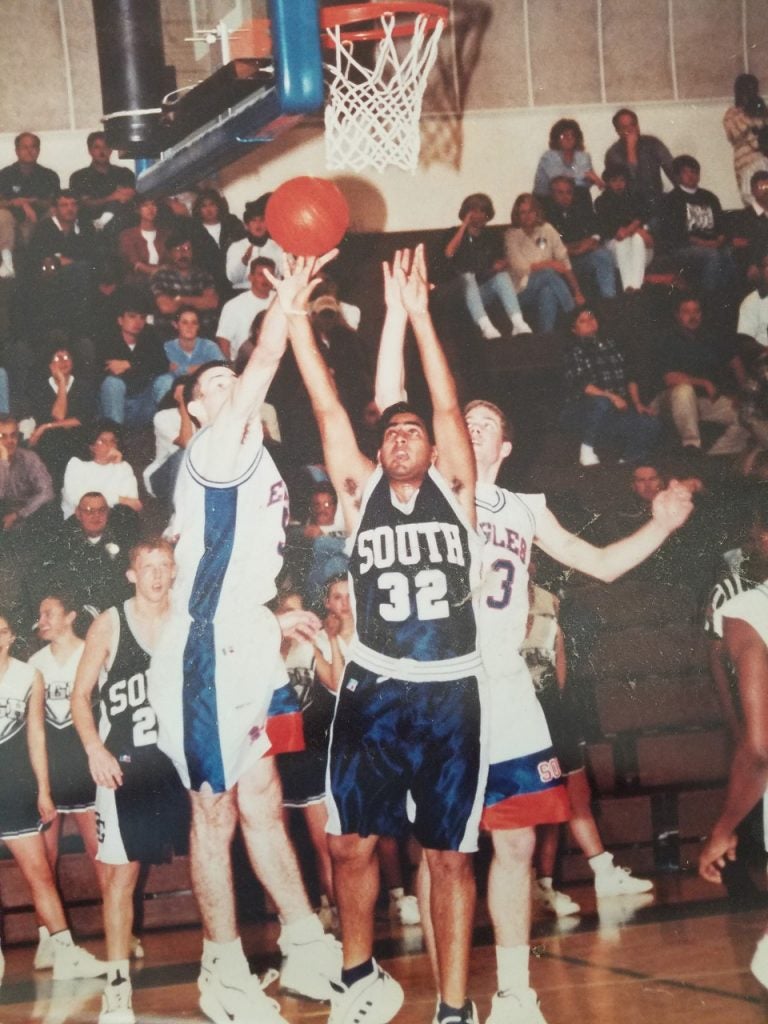

One summer during his high school basketball career, Vasef Sajid put up 28 points in an Amateur Athletic Union game against a team led by future pro Shane Battier. Sajid was an undersized point guard who did not lack confidence, and, he said, during his senior season at South Gwinnett High School in Snellville, Ga., he averaged 20 points, nine rebounds and eight assists.

But it was what happened in the wake of that AAU game that still stands out to Sajid, more than 20 years later, as the starkest example of the prejudice he faced as the son of Pakistani immigrants in a sport that tends to ignore ethnicities beyond black and white.

After that game, Sajid and his teammates were approached by a major-college basketball coach who had won a national championship. The coach shook hands with everyone on the team except Sajid. He found it strange, but he thought, maybe the coach had just missed him. Then Sajid’s high school coach found him and pulled him aside.

“Don’t get frustrated,” his coach said. “This is the kind of thing that’s going to happen to you for the rest of your life.”

Now 39, Sajid lives near Atlanta with his three small children. He briefly played college basketball at a couple of small colleges near Atlanta, but was never seriously pursued by larger colleges, despite his success both in high school and on the AAU circuit. Some of that, Sajid admitted, may have been because of his physical limitations — he never grew much taller than 5-foot-10 — but he often wonders if at least some of it may have had to do with his ethnicity. Did more than one coach not actually see him, merely because of how he looked?

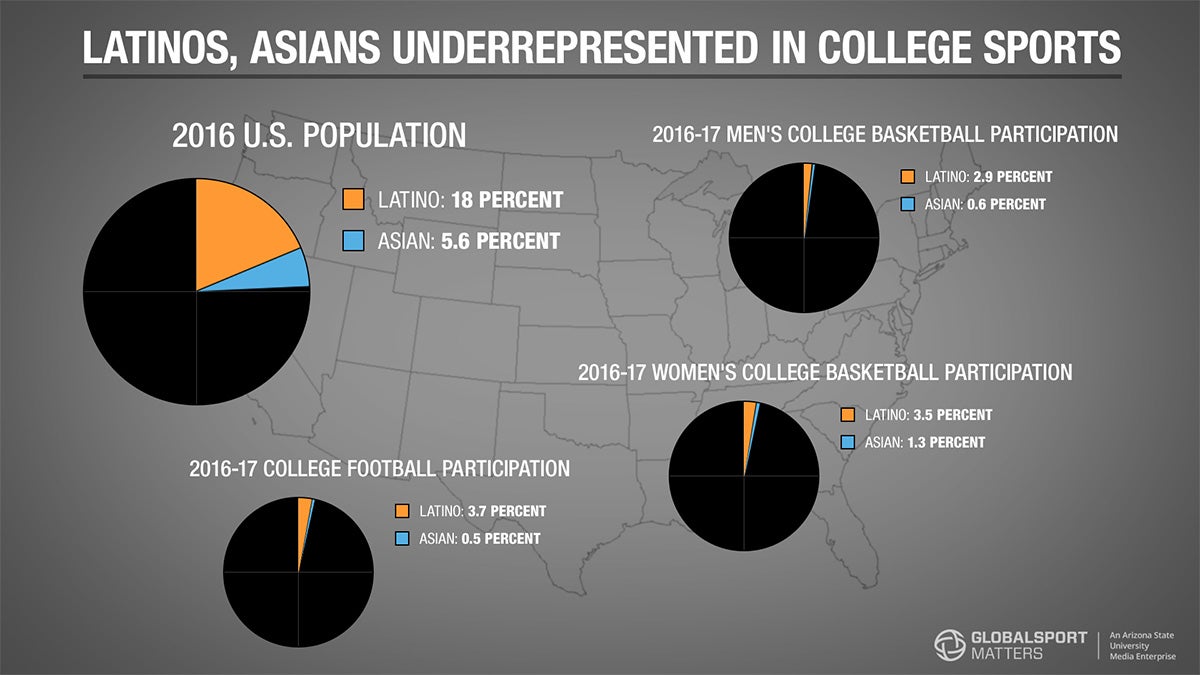

Over the two decades since Sajid graduated from South Gwinnett, little has changed — even as the makeup of America has changed. As of 2016, Hispanics made up about 18 percent of the U.S. population, and Asians made up about 5.6 percent. Yet even as both populations continue to grow, the number of Asians and Latinos participating in the two highest-profile college sports in America — football and basketball — have remained far below those levels.

During the 2016-17 academic year, 107 of 18,712 men’s basketball players in all divisions (or 0.6 percent) identified themselves as being of Asian descent, and 540 (2.9) identified as Hispanic or Latino. Among women, 215 of 16,532 basketball players (1.3) identified as Asian, and 579 (3.5) identified as Hispanic.

Compare those numbers to data from the 2007-08 season and not much has changed. That year, 99 of 17,081 male athletes (0.6 percent) and 156 of 15,307 female athletes (1.0) identified as Asian. In comparison, 473 male athletes (2.8) and 430 female athletes (2.8) identified as Hispanic.

In football, the numbers are just as stark: Of 73,057 NCAA football players in 2016-17, 386 (0.5 percent) identified as Asian and 2,734 (3.7) identified as Hispanic. In 2007-08, 447 of 64,235 (0.6) identified as Asian and 1,779 (2.7) identified as Hispanic.

“There certainly should be more (participation),” said Texas Tech University history professor Jorge Iber, whose work focuses on the history and social significance of Latinos and Latinas in sports.

So why aren’t there more Asians and Hispanics competing at the highest level in the highest-profile sports? How much of it has to do with discrimination and prejudice, and how much of it has to do with pressures inherent to Asian and Hispanic cultures?

When Stan Thangaraj was researching the experiences of South Asian athletes while a student in Atlanta, he met a volleyball coach who worked at an elite private school. That coach had heard the school’s basketball coach openly complaining about the racial makeup of his team. “How can I win with three Indians as starters?” the coach reportedly said.

Thangaraj is an assistant professor at the City College of New York who specializes in the sociocultural anthropology of Asian-Americans — and of athletes in particular. He is intimately familiar with both the internal and external pressures put upon South Asian and Asian-American athletes. Most major basketball camps and AAU organizations don’t provide the extra mentoring or training that Asian-American athletes might need, in part because such players are seen as “not really athletic,” Thangaraj said. At the same time, many immigrant parents from Asian and South Asian countries don’t fully understand the American emphasis on sports as a way of assimilating into the culture at large, Thangaraj said.

“Elders did not give a damn about their kids playing sports beyond high school,” Thangaraj said. “It was like, ‘OK, you played; you got these trophies; I’m so proud of you. It’s time to move on. It’s time to become a doctor or an engineer.’ All the stereotypical professions.”

Even for a player such as Sajid — who describes his parental influence as atypical, in that his father encouraged his athletic career and pushed him to be as competitive as he could be — stereotypes were ever-present in the South Asian community. Sajid used basketball as a way to assimilate and was purposefully aggressive on the court to prove he wouldn’t fit into those stereotypes. He was determined to defy the perceptions of the opponents who referred to him as “7-Eleven” or accused him of being a terrorist in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks.

But when Sajid sees young South Asian players today, he said, most of them “are intimidated” on the court and often are “under the strict rule of their parents.” Unlike American parents, Sajid said, South Asian parents often just drop their kids off at games and don’t stay to watch because sports feel like a secondary pursuit. “They’re not really interested in that,” Sajid said.

While there are dedicated recreational leagues for both Asian-Americans and South Asians, few role models exist to help boost the cultural importance of a sport such as basketball in those communities. The best South Asian basketball player in recent history was probably Pasha Bains, a Canadian-born athlete who played a couple of seasons at Clemson. While the Asian-American community rallied around Jeremy Lin in the midst of his breakout “Linsanity” moment with the New York Knicks in 2012, the impact has since dulled.

“The shared experience of emasculation, and being seen as only nerds, meant that Jeremy Lin could speak to the entire category of Asian Americans,” Thangaraj said. “You can see the ways in which Jeremy Lin was of tremendous impact and had incredible symbolic force.”

But that symbolism has faded as Lin bounced from one NBA non-contender to another and as his career has been hampered by injuries such as the one that kept him out for much of last season, when he played for the Brooklyn Nets. When Thangaraj gave a talk at Northwestern University long after “Linsanity” had cooled, he asked how many people could name the team that Lin played on at that moment. In a room of 60 people, one person raised a hand.

The challenges are different, of course, for Latinos and Latinas, who don’t face the same stereotypical perceptions about their lack of athleticism. But they have long been funneled into sports such as baseball. The lack of Latino and Latina role models in sports like football certainly plays a role, said Iber, who recently finished writing a book about Hispanic participation in football. But so, too, do a number of cultural factors within the Hispanic community:

- The high school dropout rate of Latinos, which, at 10 percent, has dropped precipitously over the past decade but remains still higher than the dropout rate of African-Americans (7 percent), whites (5) and Asians (3). Because many children of recent Latino and Latina immigrants have to work to support their families, Iber said, “this prevents many who have the talent to play at the high school level from doing so.”

- At least some of those recent immigrant families downplay the importance of sports in the way many Asian-American families do, although Iber said that tends to be more a prominent factor among girls than boys.

- A number of Hispanic families don’t know how to utilize the system in order to attract attention from recruiters. “They do not realize how to go about applying for scholarships, or how to post game film to MaxPreps and similar sites,” Iber said.

- Many Latino football players go to high school in small rural communities, particularly in Texas and California. Often, recruiters from major colleges will not make it to places such as the Rio Grande Valley, and Hispanic talent can get overlooked.

The good news, Iber said, is the situation is slowly changing as demographics shift, and as Hispanics settle in different regions, which explains why the Hispanic participation rate in college football has risen slightly over the course of the past decade. One high school football team in Georgia has almost 30 percent Spanish surnames this season, and similar rosters can be found in places such as Arkansas and Kansas.

Still, there are only two Latino Division I football coaches and a small number of assistants. Until that changes, until the barrier to entry for athletes is lowered and until the areas where Latino athletes thrive are visited by more coaches, the numbers may remain relatively static.

“What needs to be done to improve participation is to provide a vehicle to entry into middle-class America for these Latino families,” Iber said. “And that’s happening in many rural places.”

Michael Weinreb is a freelance writer for several outlets, and is working on a book about football as it relates to the evolution of American culture.

Related Articles

For Lin, a history of being overlooked