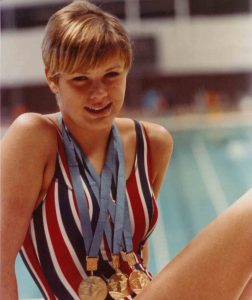

For swimmer Debbie Meyer, Mexico City in 1968 was golden

Why this matters

In 2018, Global Sport Matters and the Global Sport Institute commemorated the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium. We took a look back at the year from a global sporting perspective.

From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism. Read all the stories here.

Olympic swimmer Debbie Meyer sums up the year 1968 in one word: hellacious.

It was a year of assassinations, protests and riots. It was also a time of celebration as the countries of the world gathered for the Olympics — the shining moment in which Meyer became the first American woman to collect three swimming gold medals at the same games.

Meyer was 16 years old when she entered the Estadio Olímpico Universitario in Mexico City. She was among the youngest competitors in the games, but she was accompanied by three other students from her high school who also made it to the global stage. For 48 years, Meyer held the record for being the only American female to earn the gold in the 200-, 400- and 800-meter freestyle events in the same games. It wasn’t until the 2016 Games in Rio that fellow American Katie Ledecky repeated the accomplishment.

“The whole experience and my career leading up to it and after it, I describe it to kids by using the word supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” Meyer said. “There’s no explanation for it. There’s no word to describe the momentum, the magic, the desire, the determination, the dedication it took to get there.”

Mexico City was a destination that held some pros and many more cons. Though the city was crowded, Meyer said the people were friendly and welcoming. The athletes were greeted with a serenade as they stepped off the plane; however, right behind the welcome gathering stood men armed with guns.

“Unbeknownst to us, there were riots about a week before we arrived in Mexico City,” Meyer said. “Students rioted because they were upset the government was spending so much money on the games rather than putting it toward education. There were hundreds of students killed, and we were told only 300 had been injured. We had no clue that was the extent of it.”

Meyer was lucky: The altitude didn’t affect her like it did other athletes. Leading up to the games, athletes needed to train in areas such as Colorado Springs to prepare for the conditions in Mexico. Growing up with asthma, however, had prepared Meyer for competing in the thin air. She said when it came to the environment, her biggest issue was adjusting to the heavy smog that blanketed the city.

While many records were broken, the 1968 Olympics might be best remembered for the protests. The image of American runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos standing on the podium with two black-gloved fists raised during their national anthem is the iconic moment of those games. Much of the planning and talk about protests took place among male track athletes, so Meyer only caught a hint of what was going to happen.

“I remember Wyomia Tyus, Willye White, Barbara Ferrell and Madeline Mims were in the basement (of the athlete housing), which was the television room,” Meyer said. “They were talking about how Harry Edwards wanted them to protest about racial inequality, but it didn’t sound like they were going to go along with it.”

The women athletes had little say or role in the protests that took place. Meyer said she understood why Smith and Carlos used the podium as a platform to share their thoughts, but the controversy arose from people criticizing them for politicizing the events. Meyer said she was, at the time, more concerned about issues surrounding the Vietnam War.

She also said she understood why Colin Kaepernick — and then others — decided to protest during the national anthem in recent years.

“I’m not sure this was the right avenue to get there just like with Tommie and John,” Meyer said. “It’s backfired to a degree that nobody wants to watch football anymore, and nobody wants to follow him.”

Politics aside, Meyer returned home after the games to congratulations and parades. Her celebration actually began on the Olympic stage. After all of the countries’ flags were walked onto the field during the closing ceremonies, the athletes sitting in the stands moved down to the field. Meyer, being one of the few to walk in with the flags, was in the middle of the celebration.

“My teammate, Mike Burton from Sacramento who just won two gold medals, and I were watching the Olympic flame be put out and the Jumbotron light up with the words ‘Munich 72.’ We looked at each other and said, ‘We’re going.’”

Burton competed in Munich, but Meyer ended her competitive swimming career in January 1972. She had broken a couple of records after the 1968 Games, but she said she began to lose interest in the sport. When it began to feel like a chore, she knew she had to stop.

“I’ve been in aquatics ever since I started in 1960 whether it be teaching, coaching, swimming — I’ve been doing it,” Meyer said. “I had a swim school up until a year ago. I still teach up where I live now. It’s in my blood. When they do an autopsy, it’ll be 90 percent chlorine.”

Nikole Tower is a senior journalism student at Arizona State University