Better helmets, sensored mouth guards part of effort to make football safer

In the 2015 movie “Concussion,” Will Smith’s character, pathologist Bennet Omalu, said, “We can derive more intelligent, more brain-friendly ways we can play football.”

From rules changes such as penalizing and ejecting players initiating contact with their helmets to designing helmets to better distribute the force of a blow, there has been a concerted effort in recent years to advance the safety aspects of football so that the sport does, indeed, become more “brain friendly.”

“There is always more to be done,” said Sean Sansiveri, Vice President, Business and Legal Affairs at the NFL Players Association, the labor organization that represents the league’s players, past and present. “We like to say that the NFLPA will go anywhere that science brings us and nowhere it doesn’t. That is certainly the effort we are trying to pursue here. I think it is progressing. It’s never fast enough and we have a long way to go, but we are happy that we have come as far as we have.”

As the NFL celebrates its 100th anniversary, protecting players has certainly come a long way, from the soft, leather helmets introduced in the 1920s to the first polycarbonate helmets of the 1980s to today’s helmets that are engineered to mitigate impact forces.

A modern helmet is much more than a shiny, colorful, dome-like headgear worn by players from the NFL down to youth leagues. Rather, it can be likened to several puzzle pieces connecting to create the final, protective product.

“The helmet acts as a system,” said Thad Ide, senior vice president of research and product development for football gear manufacturer Riddell. “People tend to want to emphasize one particular aspect over another sometimes, but don’t lose sight of the fact that the helmet is a complete system designed to protect the head of the wearer.”

Flexible outer shells are designed to improve impact response, and polyurethane and synthetic rubber and foam materials are critical components of an inner structure engineered to absorb and decrease the force transferred to the skull.

An analogy often used in the design of helmet safety is borrowed from the automotive industry.

“We look at the helmet almost like a car bumper,” said Colette Foreman, director of product management at Vicis, another helmet manufacturer. “It can bend and buckle and absorb kinetic energy.”

The automotive analogy hits home with Kristy Arbogast, co-scientific director and director of engineering for the Center for Injury Research and Prevention at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and an NFLPA engineering consultant on topics injury related.

In her role with the players association, Arbogast works closely with the league’s engineering consultants to analyze injury data and advance a variety of initiatives to improve the safety of players.

“What we have tried to do is bring some of the methods and approaches that have driven innovations in auto safety to the sports world,” she said, noting that some of her colleagues working with the NFLPA have automotive safety backgrounds.

“So many of the concepts are transferable on how you manage the energy of the impact. As long as you systematically study what those impacts are, whether it be a car crash or helmet-to-helmet collision on the football field, engineers can come up with ways to manage those impacts.”

What they have come up with are helmets such as the Vicis ZERO 1, Riddell Precision Fit and LIGHT LS1, which are among those in use throughout college football and the NFL and other levels of the sport.

The University of Washington, which is where Vicis’ technology was developed, started using the ZERO 1 on a trial basis in 2016 before using them in games during the 2018 season. The helmet’s inner design includes flexible pillars.

“When you look at how the helmet is built, their goal was to increase the helmet’s ability to absorb rotational force with the little pillars inside the helmet,” Rob Scheidderger, UW’s director of medical services and head athletic trainer, said of the Vicis technology. “So, when you take an impact it can actually absorb a little bit of the impact as well as a little bit of rotational force.”

The inner-helmet construction varies in design by company. The LIGHT LS1 helmet incorporates auxetic foam padding manufactured by Florida-based Auxadyne.

Company founder and president Joe Condon uses the example of a marshmallow to describe how auxetic foam responds to impact. If you pinched a marshmallow, it would move outward or away from the point of compression. That is how conventional foam responds.

Auxetic foam does the opposite. It becomes denser at the point of contact.

“Auxetic foam is the opposite in that the structure collapses unto itself and moves to the load,” said Condon. “The more it is pressed at the point of pressure, it gets denser and denser to support the load.”

This is an example of how multiple technologies are, and can continue to be, used in the manufacture of a football helmet. Manufacturers are motivated to improve their technology through initiatives such as the NFL Helmet Challenge that will culminate in 2021 with a $1-million award to the manufacturer that submits the best prototype.

“I think that technology and material science is likely the answer,” said Condon. “I think combining different technologies is probably the optimal solution. I don’t think there is one element that will get the best solution.”

Riddell utilizes a 3D printing lattice liner system within its helmets. This technology allows the 90-year-old company to precisely fit helmets based on scans on the surfaces of a player’s head without having to create individual tools to make the liner set.

“It’s kind of the perfect technology for that sort of a custom fit system,” Ide said. “When you combine that with the way the lattices work, a combination of the right materials and the right lattice structure really allows you to do a nice job of dampening the impact energy that the players receive.”

In recent years sensor technology in helmets has become a critical piece of the head safety puzzle. The use of sensors allows for the collection of data over the course of a season or multiple seasons that can be analyzed and applied to engineer safer equipment.

“We take that and look at injury trends and impacts over the course of the season and impacts when an athlete has an injury and try to figure out if there is a trend that goes along with all of that,” Schieddeger said.

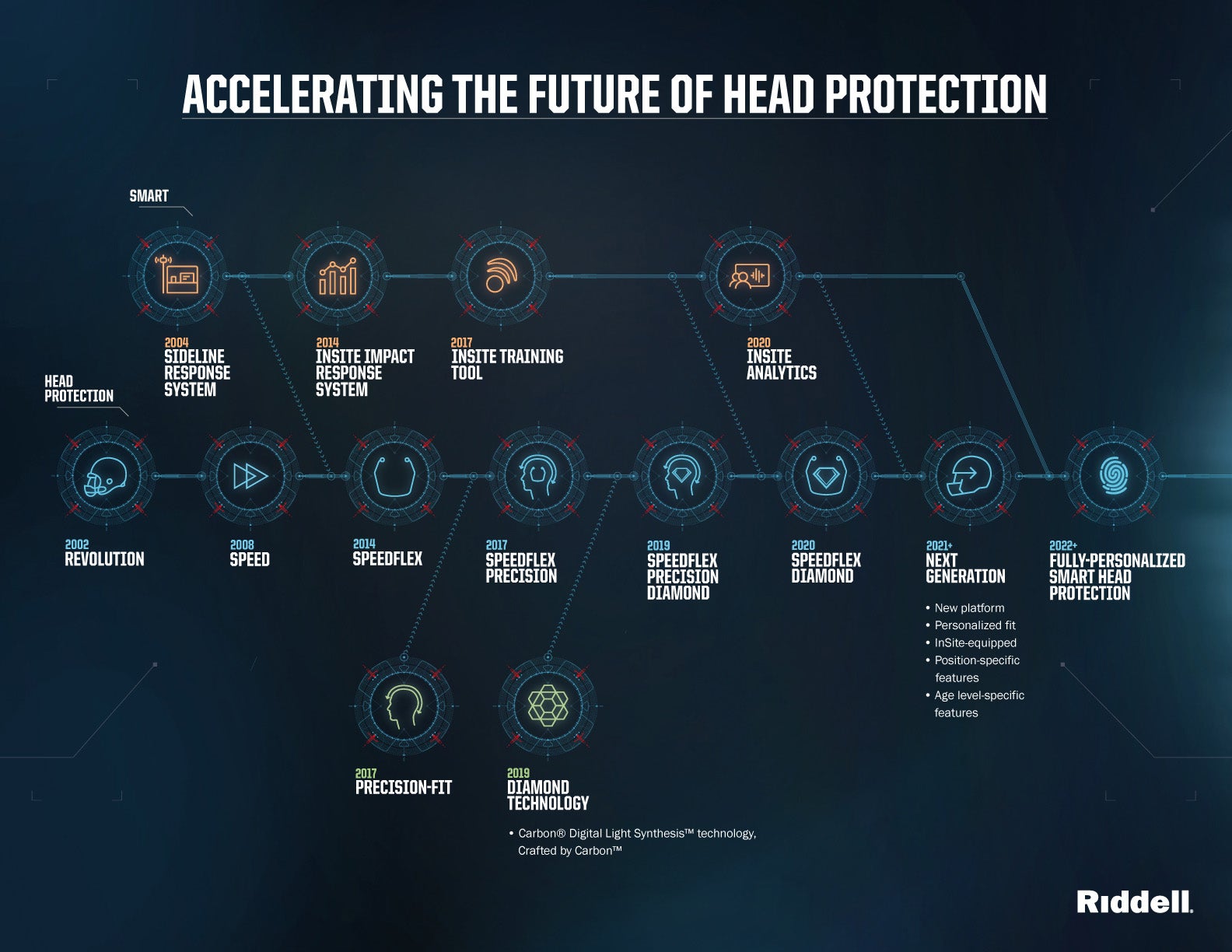

Riddell invested in sensor technology 15 years ago. Ide noted that starting in 2004, North Carolina and Virginia Tech began using the helmets in games. In 2014, Riddell launched its InSite Training Technology that informed the sideline via an alert when an atypical impact took place on the field. That evolved into being a web-based tool today that provides coaches and training staff information concerning individual player impact exposure.

“It’s done with the goal of changing behavior, reducing overall head impact exposure to the player,” Ide said. “I think five years from now it will be very difficult to purchase a football helmet that doesn’t come equipped with some sort of sensing technology like that.”

With helmet technology rapidly advancing, it may be difficult to keep track of not only what is on the market, but how effective it is.

Since 2011, researchers at Virginia Tech have played the role of Consumer Reports when it comes to helmet safety. A five-star rating system, utilized across several sports including football, identifies helmets that best reduce — but don’t eliminate — the chances of sustaining a concussion. Also, a helmet that might be ideal for one person might not be the best headgear for another player.

“No helmet is concussion proof,” Foreman said. “We don’t look at football as a sport. We look at the athletes who are actually playing the game, and our mission, our goal is that we are going to protect athletes of all ages with the helmet and protection that is best for them.”

While no helmet is concussion-proof, thanks to their innovative designs and better awareness in dealing with concussions, the NFL experienced a decline from 281 reported concussions in 2017 to 214 in 2018. There were 243 concussions in 2016 with the spike in 2017 attributed by Sansiveri to better reporting through protocols put in place by the league, such as sideline spotters.

“Last season over 50 percent of our diagnosed concussions came from self-reports,” said Sansiveri. “That just demonstrates the major cultural shift. Last year (Steelers quarterback) Ben Roethlisberger took himself out because he said he wasn't feeling right. So, if a star player feels comfortable doing that, I think that is really quite the game changer.”

Sensored mouthguards have also been developed. Mouthguards, in combination with helmets, benefit in absorbing impact.

“There is a little bit of head-impact reduction,” said Schieddeger. “If you take a hit to the chin and you are wearing your mouthguard, then it will decrease the force transmitted to the brain.”

The problem experienced with sensored mouthguards is discomfort wearing them, which has resulted in low compliance.

Last year, Bemidji State (Minnesota) University had 27 players wear sensored mouthguards made by Prevent Biometrics. They were used on a trial basis during spring practice, but not during the season.

Heather Bates, BSU’s assistant athletic trainer, noted that although the players liked the fact that the company scanned their teeth for a custom fit, some players complained that the mouthguards were too big.

Data emitted by the sensors was collected on an iPad and provided live data on the type of hits a player was absorbing. Some of the data was flawed, though, because of a common habit among football players.

“Everybody likes that they were customized,” said Bates. “But one problem that we ran into is that, of course, football players love to chew on their mouthguard. So, they couldn’t do that and those that did typically ended up not liking them. They ruined them so that it no longer fit their mouths.”

In another instance, a player’s mouthguard continuously emitted signals indicating he was repeatedly taking a tremendous amount of impact. He had shoved the mouthguard into a pocket.

There is no question that mouthguards can contribute to player safety, and not just for the protective qualities. Last year, in an effort to get more detailed data about the impact players sustain on the field, the NFL teamed with the University of Virginia on a trial basis to test sensored mouthguards, which are being used by four NFL teams this season.

“The mouthguard is not a concussion-preventing technology, rather a data collection technology,” said Arbogast. “Until you implement something like an instrumented mouthguard, we don’t really know what those impacts are. We know (the impacts) are there. You can watch on Sunday afternoon and figure out that they are, but we can’t put qualitative values to it without some sort of sensor.

“The best biomechanical place to put a sensor is kind of anchored to the skeletal part of your body versus the helmet, which moves relative to the head. So, mouthguards are a good place to anchor those sensors.”

With respect to helmets, the next wave could be designs based upon where a player lines up on the gridiron. A lineman, for example, experiences less severe blows, but there are more repetitive over the course of practice or a game. Players on punt and kick coverage and return units are more prone to high-speed collisions.

“If you think about different positions, (players) tend to wear different shoes and different pads,” said Arbogast. “I think one of the things we would like to advance, the NFLPA and the NFL together, is the idea of position-specific helmets. A lineman experiences different kinds of impacts that a quarterback does. So, can we optimize their protection by optimizing their helmet design?”

With the data the league, the players association and manufacturers continue to collect and study, that answer may not be far down the road.

Correction: Joe Condon was misidentified. He is the founder and president of Auxadyne.

Tom Layberger has spent more than 25 years as a writer, editor and web producer for various media outlets. Tom, who resides in Tampa, is a graduate of the University of South Florida. Follow him on Twitter @TomLay810

Editor’s note: For the 2019-2020 academic year, the Global Sport Institute’s research theme will be “Sport and the body.” The Institute will conduct and fund research and host events that will explore a myriad of topics related to the body.

Related Articles

Subconcussive hits still cause damage to football players

ASU researchers create messages to improve concussion reporting

New study says classic concussion treatment may not be effective

Football takes a back seat to cycling when it comes to head injuries

Playing impact sports in high school can cause ‘significant’ changes in brain

Conflicting research on CTE shows need for more study

New research, technology aimed at minimizing concussions

Study shows brain changes in football players could be from learned hand-eye coordination skills

Baseline concussion testing keeps athletes game ready