Incidents of hooliganism, racism following soccer's rise in U.S.

Hooliganism, long a major concern in international soccer, has been a documented issue for the New York City Football Club (NYCFC) since the team’s inception in 2015. A recent incident involving Irvin Antillon that occurred away from the stadium thrust the team’s issues with the neo-Nazi community into the spotlight.

Antillon, a member of the Latino skinhead group Batallón 49 (B49), participated in an attack on protestors outside of the Metropolitan Republican Club in New York City. That Oct. 12, 2018 attack gained national attention.

The arrest became a soccer issue and Major League Soccer was forced to take a stand after soccer fans and media connected the dots between the faces in a street fight and those seen in the stands at NYCFC home games. Throughout the 2018 season, the New York team’s front office received notices from fans that Antillon and members of B49 attended games with members of the now-disbanded Proud Boys, a violent, chauvinist club. They often wore neo-Nazi paraphernalia while attending games. Antillon and his cohorts reportedly sat in the section designated for NYC SC, one of two team-recognized supporter groups.

“Soccer in America and the white supremacist movement would seem to be strange bedfellows.” - Dave Hannigan, The Irish Times

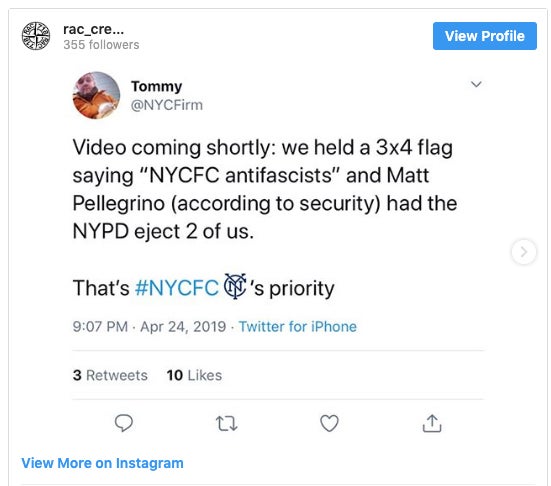

After Antillon’s arrest, he was banned from attending NYCFC games and activities, but not until fans and media amped up their criticism of the league for what they considered an inadequate initial response. Antillon’s supporters took to the River Avenue Crew Instagram’s account and other social media outlets in an act of defiance, vowing to continue attending the games and expand their activities, which include racist flyers, aggressive messaging on social media and player intimidation during matches.

Global Sport Matters contacted MLS for comment, but has not received one other than a referral to a statement issued in March.

Each year, ESPN shares Richard Lapchick’s figures related to racists incidents in sports. Last year he wrote, “For every battle won, it seems like 10 more instances of racism occurred around the world this past year. The University of Central Florida's The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport recorded 52 acts of racism in sports in the United States in 2018, up from 41 in 2017.”

At one point, those affiliated with soccer in the U.S. believed the country wouldn’t fall prey to the hooliganism and Ultra activity the international game had. In 2005, sportswriter Andrew Dixon commented on racist monkey chants hurled at black English players and the abuse of a black Brazilian player by a white Argentine player during a Copa Libertadores game. Dixon declared confidently that nothing of the sort would happen in the United States. He wrote:

“Despite this country’s shameful history regarding race relations… you will NEVER hear this type of racial abuse in the professional sports of the US. Even [in] MLS, [a majority white sport] in this country, [officials] have made it clear that this type of behavior is unacceptable and will not be tolerated.”

In his follow-up 2008 article, the soccer writer had to walk back that statement to address the viral video of fans hurling epithets at Zimbabwean forward Kheli Dube and claims by Roy Lassiter and other black players that they’d been called the n-word by other players and endured harassment by fans. Despite video proof and first-hand accounts by its players, the MLS response rang hollow.

A decade later, the problem, along with the U.S. fan base, has grown larger and continues to build via social media. The response appears to remain the same.

“These men are fascists, and their currency is violence or the threat of violence.” - a fan writing to Mike Quarino, NYCFC’s vice president of ticket sales and fan services

In a Salt Lake Tribune article, Real Salt Lake (RSL) defender Nedum Onuoha questioned when and if there can be real change. “Still, here we are where, legally we’re the same, but where culturally, we’re nowhere near the same — culturally we’re sometimes in the exact same spot and we’re having the same conversation over and over and over again.”

It’s difficult to identify and punish the activities of extremists, but ardent soccer fans of the organized supporter clubs have made it their business to alert teams of specific infractions. More and more, those fans are feeling afraid of retaliation, but many still report the problematic behavior.

“An NYCFC spokesman would not comment on specific bans, but confirmed the team has banned more than 30 people between 2015 and last year, and that some bans were the result of investigations launched in response to fan complaints,” wrote Christian Araos in The Guardian.

Fans and players continue to question the league’s actual commitment to making the stadium safe for all, at times expressing their exhaustion at bringing up the same issues. The team confirmed to the Huffington Post that fans emailed them their concerns even during their initial season, intent upon making the experience safe for all attendees.

“These men are fascists, and their currency is violence or the threat of violence,” a fan wrote to Mike Quarino, NYCFC’s vice president of ticket sales and fan services. The fan went on to comment that “my friends and I are not safe” as long as one particular group continued to attend NYCFC games, referring to the intimidating nationalist group the Empire State Ultras (ESU).

Addressing the national problem

As Major League Soccer (MLS) kicked off its 24th season in late February, the league shared an updated Fan Code of Conduct. As its fan base widens, the league faces an accompanying increase in racist, homophobic and discriminatory actions in the stands during soccer matches. These acts prompted the new specific language and penalties. Are such actions new or unexpected? Hardly. The defined policy and punishment are the latest league attempt to curb the problem or, at least, quell the concerns of worried supporters.

“MLS finds itself attempting to keep racism and bigotry out of its games while encouraging fans to be passionate and expressive about their teams. It’s just that at this moment, many of those fans are as passionate and expressive about their politics as they are about soccer,” Araos wrote.

The issues aren’t isolated to a single team. Across the country, fans of the Los Angeles Football Club (LAFC) shouted the homophobic “P chant” at players on the field during a November 2018 match. The Galaxians, a supporter club, addressed the matter on Twitter, denouncing the acts that didn’t result in any ejections.

Freelance writer Julia Poe covered the match and noted fans shouted the slur at least 10 times during the game, growing louder and stronger after a JumboTron message reminded the fans of league policy. Outsports writer Cyd Ziegler sent a message to the league asking for follow-through and support for the LGBTQ fan community.

“We look forward to working with the team, our fellow LAFC supporters, and fellow LGBTQ supporter groups throughout the league to eliminate the chant for good in the 2019 season. And we call on the MLS to show some real leadership on this issue, beginning right now, in the postseason. Videos, talking points, and ‘policies’ are not enough: there have to be significant penalties imposed for this behavior at the league level in order to eradicate it for good.”

Will the updated Code of Conduct make a difference?

As soccer’s fanbase increases in size and relevance, the gravity of the situation grows and could reverse the popularity of the sport. A 2017 Gallup poll revealed the coveted 18-34 demographic now ranked soccer second to football, making it even more imperative the league proactively address issues that might hamper attendance. Fans and players have questioned the league’s seriousness when responding to reports of aggressive fan behavior.

MLS crafted the Don’t Cross the Line anti-discrimination campaign, and, for the past five years, it implored fans to take a stand against bigotry and homophobia. The pledge was clear: “We will not tolerate discrimination, bias, prejudice or harassment of any kind. Don’t Cross the Line promotes unity, respect, fair play, equality and inclusion throughout the soccer community.”

How far, though, does the league go in support of that pledge proves the bigger question.

"It transcends sports; it is society. For as much as it is getting better, the bottom line for me is it feels like legally now you can’t discriminate against people, but culturally, it’s very easy to and it’s very easy to in the majority of places around the world which is, which is unacceptable in my mind.” - Real Salt Lake defender Nedum Onuoha

On March 3 when Jonathan Tannenwald, soccer reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, questioned MLS Commissioner Don Garber about the reported incidents of racism and homophobia by fans both inside and outside of stadia, the commissioner offered a tepid response, much to the dissatisfaction of the followers in Tannenwald’s Twitter feed:

“And our job is not to judge and profile any fan. It’s to manage how our fans are interacting with each other, and how they’re behaving at our stadiums. So, at this point, that’s how we’re going to address the situation. The last thing this league is going to do is start getting into profiling who people are and what their backgrounds are,” Garber replied.

His answer was met with memes and angry posts by soccer fans who felt they deserve more.

Who’s really committed to change? Players speak out

Onuoha spoke candidly about the topic of discrimination in an interview with MLS’s Extratime.

Onuoha’s concerns mirror those of other players and fans. He worries even after everyone’s focus targets the problems, attention wanes as more exciting sports topics appear. That means little if any progress is made in addressing the painful, sometimes violent, acts.

“The headlines for this type of thing exists on the back pages, and the back pages change every single day depending on whichever sporting event is coming up next,” Onuoha said. “So very quickly it can go from being the biggest thing to just being something that was said previously, even though it’s something goes … It transcends sports; it is society. For as much as it is getting better, the bottom line for me is it feels like legally now you can’t discriminate against people, but culturally, it’s very easy to and it’s very easy to in the majority of places around the world which is, which is unacceptable in my mind.”

Onuoha is just one of the players around the globe demanding teams, leagues and media be held responsible for their role in the rising number of attacks, both in the physical and the virtual world. Premier League (PL) defenders Danny Rose (Tottenham) and Chris Smalling (Manchester United) led a 24-hour social media blackout on April 20 in protest of the vitriolic and hateful treatment players and their families are subject to on social media platforms. The boycott was met with vicious backlash, proving again the perpetrators felt emboldened to be abusive.

Mia M. Jackson is a writer based in Germantown, Md.