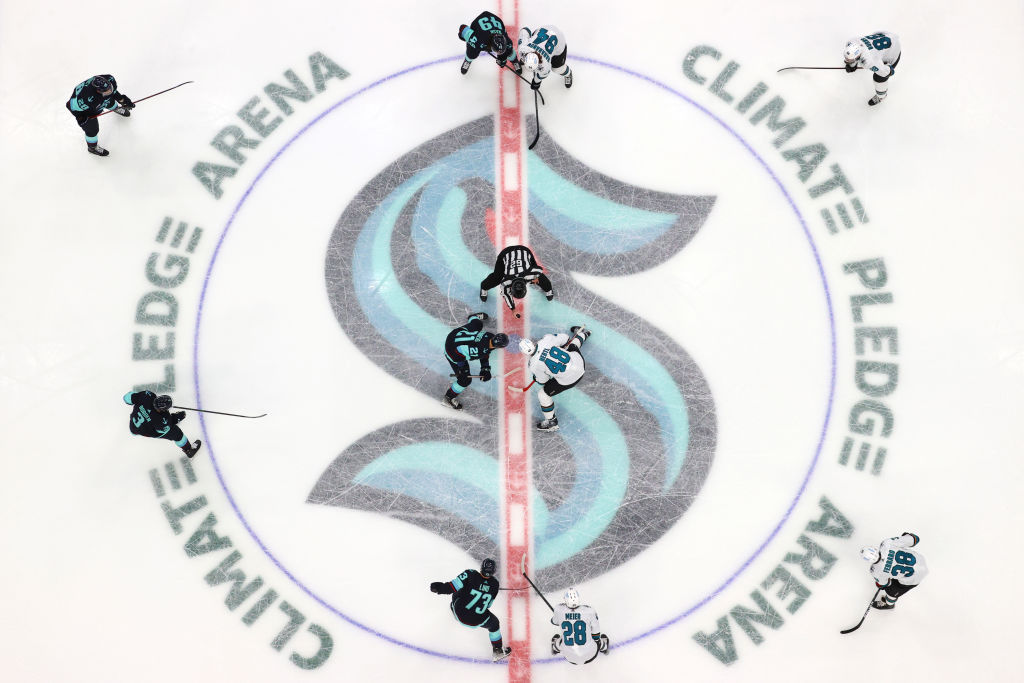

Seattle’s Climate Pledge Arena Wants to Set a ‘New Sustainability Bar for Sports.’ Can it Succeed?

Why this matters

The sports industry is beginning to reinvent itself with more sustainable business practices, and Climate Pledge Arena, home of the Seattle Kraken and Storm, has tried to use a sponsorship from Amazon to blaze a carbon-neutral trail in sport.

When Amazon announced that it had purchased the naming rights to Seattle’s newly rebuilt multipurpose arena in June 2020, it wasn’t the usual deal to slap a corporate moniker on a sports venue. First off, it wasn’t Amazon’s name going on the former KeyArena — then in the midst of a complete reconstruction to become the home of the National Hockey League’s new Seattle Kraken and the Seattle Storm of the Women’s National Basketball Association. Rather, the building would be known as Climate Pledge Arena, named after Amazon’s campaign to inspire businesses to commit to “net-zero” carbon emissions by 2040.

And with that would come a pledge for the venue itself: Amazon, developer Oak View Group, and the Kraken owners vowed that Climate Pledge Arena would “set a new sustainability bar for the sports and events industry.” Power would be generated by renewable resources wherever possible, and other strategies would be put in place to offset the venue’s remaining carbon footprint.

“Our goal is to be the most progressive, responsible, and sustainable venue in the world,” said Oak View CEO Tim Leiweke, whose brother Tod is co-owner, president, and CEO of the Kraken. “It is not just about one arena — it’s a platform for us to step up and heal our planet.”

It’s a laudable goal, particularly in light of the faltering attempts to fight climate catastrophe in the 30-plus years since scientists first predicted a dramatic rise in global temperatures. The U.N.’s latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report stated that greenhouse gas emissions must peak and start to decline no later than 2025 in order to stave off what U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called “catastrophic” consequences, including flooded cities, unprecedented heat waves, and massive water shortages. Still, emissions continue to grow worldwide, with few signs of significant slowing.

But along with increased concern about the climate have come fears of “greenwashing,” when companies claim that they are adopting planet-friendly policies without providing actual evidence. With that in mind, how much of an impact will Climate Pledge Arena really make?

Pro sport is one of the more carbon-intensive industries, with power needs for everything from stadium and arena lighting – Climate Pledge Arena itself features a record 224 video boards – to the athletes’ frequent travel. When the four major U.S. sports leagues adjusted their schedules during the pandemic, it was estimated that their corresponding reductions in air travel would save more than 26,000 tons of carbon emissions a year if adopted permanently. (Instead, schedules went back to normal in 2021, as did carbon emissions.)

The Climate Pledge team is going beyond the games themselves to make an even greater impact. To show their commitment, the arena’s builders have sought certification from the International Living Futures Institute, a Seattle-based nonprofit that promotes green construction worldwide. Climate Pledge will be the first arena to gain the certification, said Rob Johnson, vice-president of sustainability and transportation for the Kraken and Climate Pledge Arena.

This comes with four requirements. First, the arena must totally decarbonize, Johnson said, “so there’s no fossil fuel use in the building, full stop.” Second, there must be a “visible” component of onsite renewable energy generation. Third, offsite energy must be from new renewable sources. And fourth, building operations and capital must be offset by the purchase of credits earned from reducing carbon emissions elsewhere. “That’s how you get to net-zero carbon,” Johnson explained.

The first step toward net-zero emissions, Johnson said, was to convert the arena’s power to all-electric, eliminating the more traditional use of natural gas for things like heating, cooling, and refrigerating the ice rink. Solar rooftop panels will contribute a small amount of power — about 1% of the arena’s total usage — while the rest will be run off of Seattle’s electrical grid.

The city’s power system is already pretty clean, Johnson explained. Most of its electricity is generated by hydroelectric dams elsewhere in Washington state. Since the certification by ILFI requires use of “new” renewable sources, not existing ones, the arena also plans to purchase and then retire renewable energy credits from a local wind farm to compensate for power that it’s pulling from the existing grid.

Eventually, said Johnson, the arena plans to partner with the city’s power department to purchase energy from a new solar farm the city is set to open in the next two years.

But a building’s carbon footprint doesn’t stop with keeping its lights and video boards on. Nor does it end on the host teams’ off nights. “When (rapper) Tyler, the Creator comes on Friday, we need to account for the 25 vehicles that come along with his tour: 18 semi trucks and seven tour buses,” Johnson said. “Then, we need to account for the travel behavior of the 17,000 fans that are coming to see Tyler, the Creator. And we do account for the carbon footprint of the food that’s consumed at the building,” as well as beverage and souvenir sales and staff travel.

There’s also the footprint of the arena itself. For the Climate Pledge Arena renovation, this involved an almost complete rebuild under its existing (and historic) roof. That amounted to 35,000 tons of carbon, according to Johnson — lower than it would have been if the arena’s roof hadn’t been reused, but still as much as driving about 7,500 cars for a year.

To calculate the building’s entire carbon footprint, Johnson said, the arena operators have constructed an enormous database — hosted, not surprisingly, by Amazon Web Services. “In late spring, early summer of this year, we will start with a public-facing dashboard component,” he added. “And then at the conclusion of the first year of operations, so October of 2022, we will be able to say, ‘We believe the carbon footprint of the building was X, and we’re making investments in Y’ that equal or exceed the building’s total emissions. Those investments will come in the form of more carbon offset purchases."

It’s an ambitious goal, and one that Barbara Haya, director of the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project at University of California-Berkeley, said is deserving of praise. “The things that really excite me from this is that they’re going to be 100% renewable energy from plants that they helped build themselves; that they’re zero waste, zero single-use plastics,” Haya said. “It’s really good to see these direct reductions in their impact.”

But the calculations become more murky when it comes to carbon offsets. First launched in the late 1980s to provide a mechanism for polluters to counterbalance their greenhouse gas emissions and later expanded under the U.N.’s 1997 Kyoto Protocol, carbon offsets are devilishly hard to police: Just because a project — say, preserving forests — claims to be reducing carbon emissions doesn’t mean that it really is; in many cases, companies can claim credit for investing in carbon-reduction projects that would have happened regardless.

The Seattle arena is making two kinds of purchases to offset its energy usage: renewable energy credits and carbon offsets. The former will be bought from Puget Sound Energy, which runs a wind farm on the lower Snake River in the eastern part of the state. (Renewable energy credits are a way of assigning certain renewable energy to a particular buyer, since in practice there’s no way to know who’s using which electrons.)

According to a PSE factsheet, this wind farm was completed in 2012, raising questions about how it qualifies as “new on- or off-site renewable energy,” as required by ILFI. (ILFI said it could not comment on the arena’s specific net-zero claims, as it has yet to formally submit its renewable energy plan). Indeed, some environmental groups recommend that renewable energy credits not be counted toward net-zero carbon claims, precisely because they don’t actually create any new renewable power, but just reassign what’s there already.

Asked about the use of the credits, Johnson said, “Our commitment to being 100% powered by renewable energy means that we’re buying those credits from PSE’s previous project, retiring those credits, and then standing up a new renewable energy solution with Seattle City Light.” On top of that, he said, the arena will make up for any energy carbon burned by fans — or Tyler, the Creator’s tour buses — by purchasing carbon offsets from sources yet to be determined.

The question of whether renewable energy being funded to compensate for carbon emissions is really new is important for more than whether the arena gets its net-zero seal of approval. This is known in the climate world as the “additionality” problem, and it’s a big one. Haya noted that for her PhD research, she looked at renewable energy projects in India and found that most of them already had enough incentives in place from India’s Ministry for New and Renewable Energy that offsets didn’t actually increase the amount of clean power produced. “In the end, it looked like most of these projects would have happened anyway; offsets weren’t the make-or-break factor,” she explained. “The purchase of the credits didn't truly cause any change on the ground, so they shouldn’t be used as offsets.”

A 2017 study by the European Commission found that 85% of offsets used by the European Union under a U.N. carbon-credit protocol failed to reduce carbon emissions because the renewable energy projects would have been built regardless. And the study’s authors found that if anything, the results were getting worse, as offset buyers scrambled to find projects to invest in, even those with dubious benefits.

Related: The Electric Future of Auto Racing Will Look, Sound and Feel Different

Findings like these, Haya said, have led to a massive crisis in the offsets market that is still not resolved. “The offset market is in a state of tremendous flux at the moment, as more and more companies and universities and cities and sports facilities plan to go carbon-neutral and need to buy carbon offsets, and recognize there’s a real problem with quality on the offset market,” she said. Several carbon-reduction projects, including the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, are working on creating better-quality ratings for offsets, she noted, but these are still a work in progress.

Another big question is whether Climate Pledge Arena inspires other sports venues to follow suit. It’s going to be a challenge, Johnson acknowledged, since not every arena will be engaged in a massive rebuild that will enable it to retrofit all of its power usage. But even smaller steps, he said, can be worthwhile.

“It is not difficult for arenas to think about their waste stream and how they could divert, with their partners, more of their waste away from landfills and into composting and recycling,” he said. Once a sports venue begins conducting an accounting of its climate impact, he added, it becomes apparent how to cut emissions, whether that’s by sourcing food or t-shirts from more local sources that require less shipping to get to the arena, or even simpler measures. “Eliminate single-use plastics? Most buildings could do that tomorrow, and switch from plastic bottles to aluminum cans,” Johnson said. “That’s a simple and easy change that would have a huge impact on the environment.”

Derik Broekhoff, senior scientist for the Stockholm Environment Institute in Seattle, agreed that the Kraken’s arena deserves credit, even if a “net-zero” claim may be pushing it.

“It appears they are making a good-faith effort to comprehensively minimize the carbon footprint of the arena,” he said, noting that the arena operators are following what’s known as a “mitigation hierarchy” by reducing emissions wherever possible, and only then looking to offset them. That said, he hopes that buying offsets will be seen as “penance, not absolution”: not a proof of eliminating carbon emissions from a building so much as an acknowledgement that zero carbon isn’t always achievable.

Haya, meanwhile, recommends that venue operators steer clear of claims of being “net-zero,” no matter how good they may look on a press release, and stick to goals that can actually be proven without dubious math on offsets.

“The direction that these carbon-neutrality goals seem to be going is not to focus on the word ‘net’ or on the number zero, but instead focus on reducing the direct emissions as the top priority,” she said. “If there’s zero fossil fuel emissions on-site, that’s amazing, and they should say what they’ve done.”

Monthly Issue

The Sustainability of Sport

Sport is a large-scale global pursuit that brings together people and places, often creating deep roots with the environment in which it is played. As a result, sport both contributes to ecological change and is affected by it.

As efforts intensify to address decades of carbon emission, commercial growth, and environmental deterioration, sport can take the lead in championing progress. If current trends continue, however, sport could face some of the more serious consequences of a changing Earth.