Gymnast Vera Caslavska's Silent Protest Spoke Volumes

Why this matters

In 2018, Global Sport Matters and the Global Sport Institute commemorated the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium. We took a look back at the year from a global sporting perspective.

From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism. Read all the stories here.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s raised fists during the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympic Games is an iconic moment in sports history. But they were not the only ones to take a stand against oppression during those games.

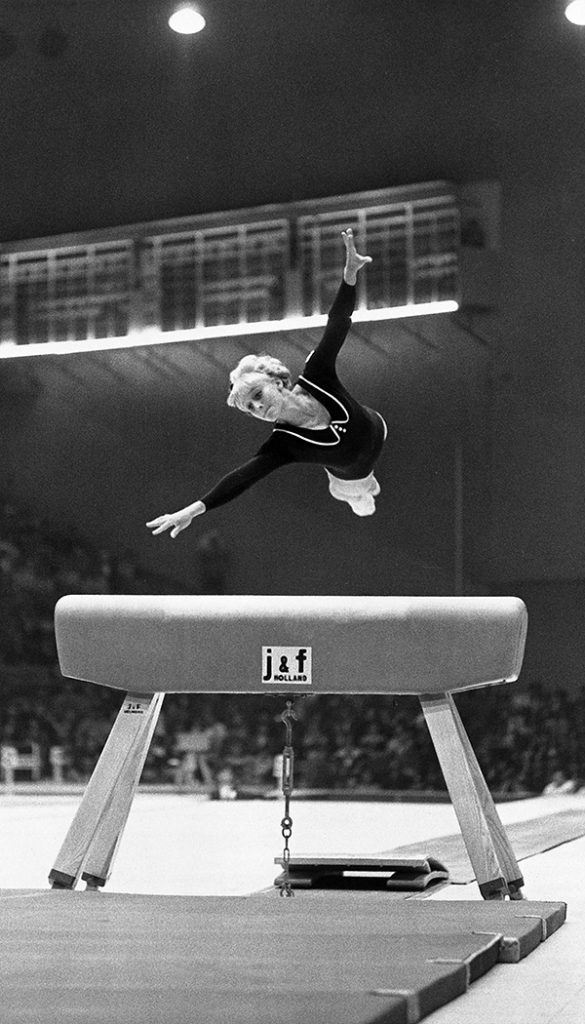

Vera Caslavska of Czechoslovakia was the most dominant gymnast of her time. A winner of seven Olympic gold medals and 11 Olympic medals in total, she was the original worldwide superstar gymnast. She entered the 1968 Olympics as a major favorite. She was also an activist against the harsh communist regime present in her country.

In 1968 Czechoslovakia gained a new leader, Alexander Dubcek, who was more liberal. He eased the harsh censorship regulations on the country. He allowed more travel outside of the country and free expression by the citizens. This became known as the Prague Spring.

Taking advantage of the new freedoms, Caslavska was one of thousands who signed a manifesto in July 1968 that called for democratic change, a development that was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s invasion of the country in August of that year.

The invasion sent Caslavska into hiding over fears of imprisonment. She went to a remote village in the mountains of Czechoslovakia and lifted potatoes and shoveled coal for her workouts

Mere days before the start of the Olympics she gained permission from her government to compete in Mexico City.

That approval turned out to be her biggest obstacle. Caslavska dominated in Mexico City. She won her second consecutive overall women’s gymnastics title and thrived in the four individual gymnastics events. Two controversial judging decisions went against her in the balance beam and the floor exercise, which forced her to take the silver in the beam and share gold with a Soviet gymnast in the floor exercise. Many experts believed she should have won the gold in both outright.

In the medal ceremonies for those two events, she made a quiet, anti-Soviet demonstration on the medal podium. As the anthem played and the Soviet flag was raised, she turned her head down and away from the flags. This display made her incredibly popular worldwide — even being reported as the second-most popular woman in the world at the time, behind Jackie Kennedy, in one survey.

Life wasn’t easy for her though.

“After ascending the summit of Olympus, the journey downward did not exactly follow the well-trodden path,” Caslavska once said. “It consisted of rocks, gorges and a bottomless pit.”

She was investigated for being an “unhealthy influence” by the Soviet leadership. She was barred from competing and was denied coaching jobs when she refused to take back her political views. She instead went on to coach the Mexican gymnastics team for 11 years.

In the 1980s, the IOC awarded her the Olympic Order for her distinguished contribution to the Olympic movement. She remained, up until her death in 2016, a worldwide hero for standing up to one of the most powerful empires in the world.

Max Bechtoldt is a senior journalism student at Arizona State University