Paul Hoffman: Harvard rowers supported OPHR in 1968 'because you are right'

Why this matters

In 2018, Global Sport Matters and the Global Sport Institute commemorated the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium. We took a look back at the year from a global sporting perspective.

From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism. Read all the stories here.

In 1968, Paul Hoffman and the Harvard rowing team edged out the University of Pennsylvania by five one-hundredths of a second in the US Olympic Rowing Trials to secure their spot in the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics.

Instead of immediately heading back to Cambridge to start training, Hoffman and some teammates went to see a professor at San Jose State University named Harry Edwards. He started the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which protested not only against racial segregation in the United States but for human rights for all people.

The Harvard rowers showed up at Edwards' office hours the same way they would if they were at Harvard, in suits and ties. The meeting cemented a partnership to fight for human rights together. After meeting Edwards and learning about the goals of OPHR, Hoffman and the team knew they wanted to participate.

“The first group of people to support what we were doing at San Jose State was the Harvard eight-man crew,” said Edwards, who went on to ask why a group of Harvard students were choosing to get involved. Their response was “Because you are right. We are better than we have shown and we support you.”

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the OPHR protest of Tommie Smith and John Carlos' raised fists on the medal podium at the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics, Edwards and Hoffman reunited as part of panel sponsored by two Arizona State University programs — the Global Sport Institute and the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy.

Hoffman was the coxswain for the Harvard rowing team in 1968, but is better remembered for his actions preceding the men’s 200m medal ceremony. He gave Australian sprinter Peter Norman his OPHR button so that he could stand in solidarity with Smith and Carlos in protest.

After meeting Edwards and learning about the goals of OPHR, Hoffman and the team knew they wanted to participate.

“I think there was a very large aspect of wanting to not be embarrassed and shamed by inaction,” said Hoffman. “[Instead of boycotting] We’ll try and start a dialogue. What we promise to do is to write to every single new member of the Olympic Team that is selected and ask them to join the conversation about what our black teammates are talking about.”

“It really is a tribute to Harry that if you are in sport, you are not out of the world,” Hoffman said. “If you are in sports you have an obligation to use whatever platform you have.”

While they didn’t think that they were making an impact, the solidarity and potency of the message of support the Harvard rowing team showed Edwards and the OPHR was extremely important to broaden the organization’s scope of influence for white Americans to believe in their cause.

“The necessity of whatever you are doing must have the potential to include everybody,” Edwards said. “Because to the extent we leave anybody out, we leave a combustible area of life and eventually it will explode.”

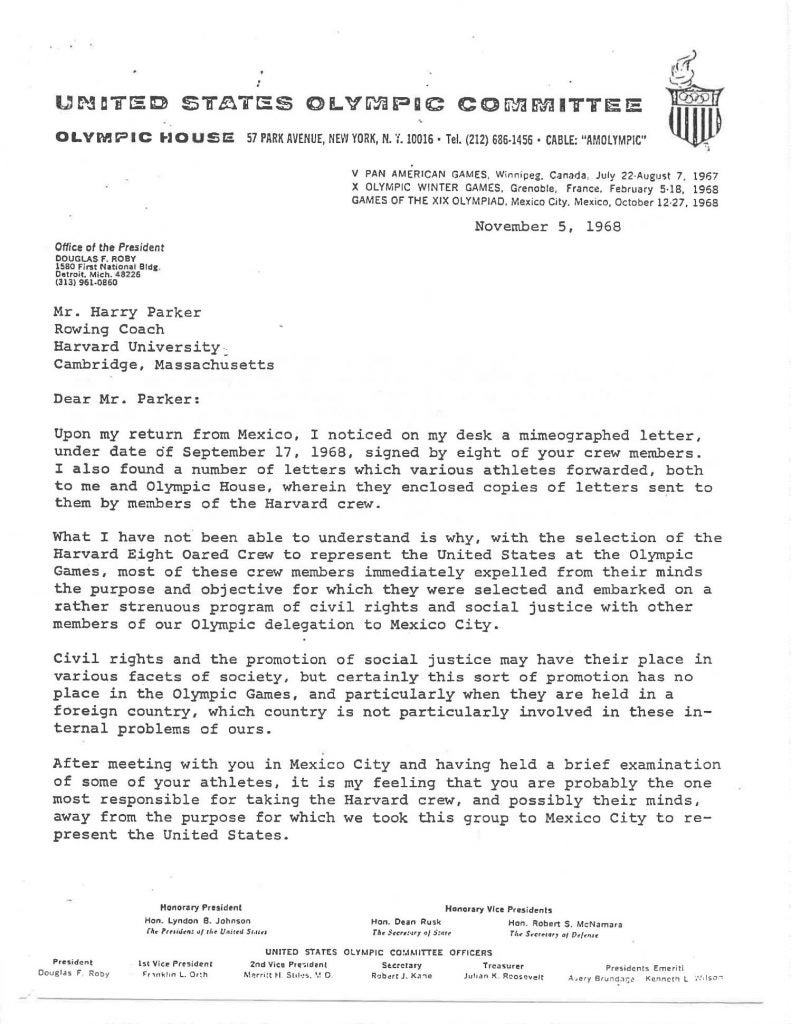

Their campaign, however, was not met by universal support. In a letter dated Nov. 5, 1968, former USOC President Douglas Roby responded to a letter written by Hoffman and the rowers saying that “Civil rights and the promotion of social justice may have their place in various facets of society, but certainly this sort of promotion has no place in the Olympic Games…”

He also went on to say that because of their participation in the OPHR, a “serious intellectual degeneration has taken place in this once great University.”

“When you face this in organized sport, and you face somebody who is clearly in a position of power above you, you can’t be too judgemental.” Hoffman said.“But when you see real bravery, you have to salute it.”

Learning from the past is something that Edwards strongly believes in. He mentored Colin Kaepernick before his kneeling protest took place about how to frame his approach to his protest and the potential consequences of his actions.

Protest without an extensively thought-out plan, Edwards believes, is the reason that 50 years after Carlos and Smith’s protest we are still not, as a society, where we need to be.

“Activism divorced from strategic planning and analysis is conducive to nothing but chaos and contradiction,” said Edwards. “There isn’t that internal structure such as the [OPHR] that frames up the internal, strategic-disposition of the athletes involved.”

One reason for this is, Edwards says, is the rise of new forms of communication and forum, such as social media.

“Social media changes everything. You can get one individual taking a knee but then it goes viral and all of a sudden you got 10 million people who are voicing an opinion about it. Back in the day in the 1960s I’d make 100 telephone calls on my rotary phone a day.”

Regardless of the medium, the conversation Edwards and Hoffman look to evoke in society today is that in the face of opposition and power, and across racial lines, similarly minded individuals can band together to make real social change on whatever platform they were given.

Ross Andrews is a senior journalism student at Arizona State University