Bob Beamon's historic Mexico City long jump almost didn't happen

Why this matters

In 2018, Global Sport Matters and the Global Sport Institute commemorated the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium. We took a look back at the year from a global sporting perspective.

From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism. Read all the stories here.

Two feet.

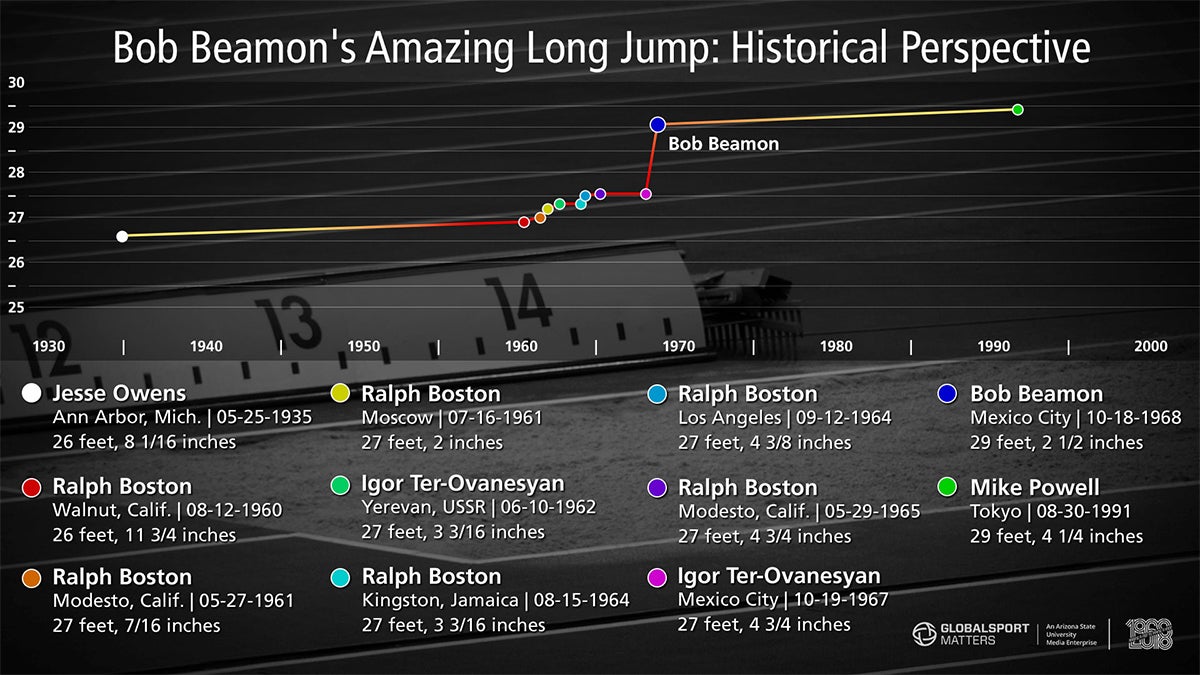

Two feet might not sound like much except for when those 2 feet are the distance a world record is broken by, especially in the long jump. For Bob Beamon and the rest of the sports world, Oct. 18, 1968 is the date 2 feet meant immortality.

Beamon was born in Queens, N.Y., in 1946. When he was young, his mother passed away and he fell in with troubled crowds. He credits sports with getting him through that hard time in his life. During this time, he joined a gang and dealt drugs before he was sent to a reform high school. His athletic success was a large factor in him being able to attend college.

Beamon originally attended North Carolina A&T, at which he competed on the school’s track team. He chose North Carolina A&T to be near his ailing grandmother. However, he grew to dislike the experience at the school and transferred to growing track powerhouse Texas-El Paso after his grandmother passed away.

At Texas-El Paso, he quickly grew into a superstar. He perfected a unique technique in which the jumper almost walked into the air. The result was his winning 22 of 23 events he participated in before the Olympics.

Beamon wasn’t just all about jumping. His political stances and desire for equality led him to participate in a boycott of a meet against Brigham Young University. Beamon believed BYU, a Mormon school, had unfavorable views toward racial progress. That protest led to his scholarship being revoked shortly before the Olympics.

At the Olympic trials, Beamon showed a glimpse of what was to come when he set a personal best that would have been a world record at 27 feet, 6 inches, but the effort was wind-aided, disqualifying it for record recognition.

Once Beamon was in Mexico City, he nearly missed a chance at history. Faults on his first two jumps meant he was in serious danger of not qualifying for the final round. He successfully qualified on his third and final jump.

Beamon’s mind was clear for his historic jump.

“My mind was blank during the jump” Beamon said. “After so much jumping, jumping becomes automatic. I was surprised as anybody at the distance.”

That surprise was delayed though. When the officials originally measured the length of the jump, they did so in meters, not feet. Beamon did not know the conversion at the time. But he knew he made history once his jump of 29 feet, 2 ½ inches was announced, breaking the previous record by nearly 2 feet.

Before Beamon set the record, it had been broken eight times between 1960 and 1967. In contrast, Beamon’s jump was the worldwide standard for 23 years until Mike Powell broke it, although not at the Olympics. Beamon’s Olympic record still stands.

Max Bechtoldt is a senior journalism major at Arizona State University