Kenyans launched distance dynasty in Mexico City

Why this matters

In 2018, Global Sport Matters and the Global Sport Institute commemorated the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium. We took a look back at the year from a global sporting perspective.

From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism. Read all the stories here.

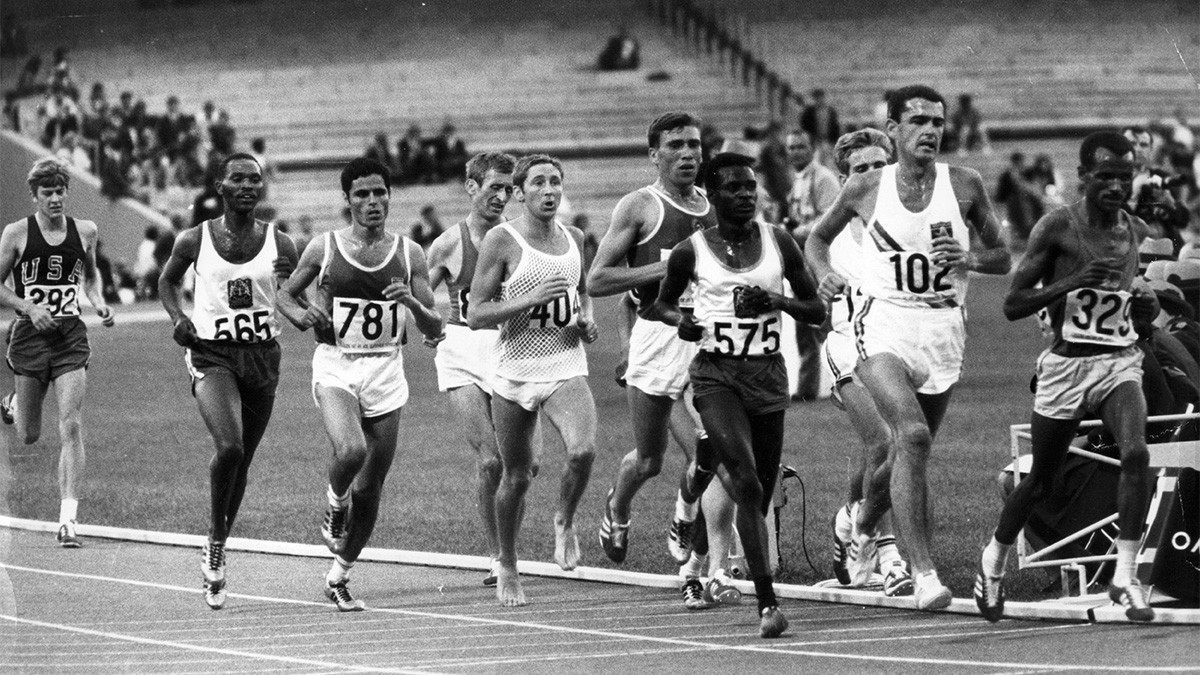

At the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Kenyan distance runner Kip Keino pulled off one of the greatest upsets of all time, defeating heavy favorite Jim Ryun in the men’s 1,500 meters and setting off an era of East African dominance in long distance running. But what led up to Keino’s win in Mexico City?

The current Kenyan domination in long-distance running cannot be overstated. In his book East African Running: Toward a Cross-Disciplinary Perspective, John Bale wrote that in 2004 the Kenyan population was 32 million people, which roughly accounts for 0.5 percent of the world population. Yet 51 percent of the top 10 male performances from 800 meters to the marathon have been run by Kenyan athletes. In September 2018, Eliud Kipchoge set the world marathon record at 2 hours, 1 minute and 39 seconds and won his 12th major marathon in his last 13 events. How did this domination start?

If someone asked what led to Keino’s victory in 1968, many would have said the runners were simply natural athletes with raw talent, which was a stark contradiction to the stereotypical view at the time of Africans being savages who were made listless with the African heat and humidity.

In reality, East Africa has a long history when it comes to running, and much of it was started by missionaries, the military and other European agencies in schools.

In a 2017 journal article by Dr. Peter Bukhala, a senior lecturer at the Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology in Kakamega, Kenya, he posited that the Kenyans’ success may trace its roots to the practice of cattle raiding that was common among certain tribes since the late 19th century. He believes superior running abilities may have been a prerequisite for being a cattle raider.

The start of organized sport in East Africa came in 1924 when James Orr, the colony’s first director of education, helped establish the Arab and African Sports Association (AASA). The formation of the AASA helped to modernize sport in Kenya, which was a combination of western influences and local tradition.

In 1926, the Alliance High School was founded in Kikuyu, Kenya. A master of the all-African school was Edward Crittenden, who was London educated and a sprinter in school. He was a believer in brawn over brain and wanted to establish a base for athletic training.

With the establishment of the Kenyan Amateur Athletics Association in 1951, the country was allowed to begin competing in major international competitions, including the Empire Games.

The first visit of Kenyan athletes to Europe came in 1954 at the English AAA championships. Many thought the Kenyans would succeed in the high jump and maybe the javelin. Lazri Chepkwony was the first Kenyan long-distance runner to compete in a major European event. He competed in the six-miles championship, but dropped out after 15 laps. Many critics claimed it was because he was not smart enough to pace himself. The next day Nyandika Maiyoro competed in the three-mile run and finished in third place, beating many of the best British runners. This showed the Europeans that the African runners were to be taken seriously.

In the 1960 Rome Olympics, Ethiopia became the first East African country to win gold in a distance competition when Abebe Bikila won the marathon. It was a key moment in the history of African running. By the mid-1960s, Kenyans were competing at the world level on a regular basis.

While the Kenyans had been competitive on the world stage before the Mexico City Olympics, 1968 was the year they became dominant. Before the 1968 Summer Games, Kenya had won one track event: Wilson Kiprugut won a bronze medal in the 800 meters in 1964.

What aided the Kenyans in Mexico City? The altitude. The Kenyans were used to running at higher altitudes than anyone else, so they held a major advantage when it came to stamina.

The 1,500 meters was the first indication of the future distance domination. According to a 2013 report by Gregory Warner for NPR, Keino was told not to compete that day because he had been diagnosed with a gall bladder infection just a few days prior. Gall bladder infections are at their most painful when the sufferer is breathing hard, which obviously came into play when running long distance.

Keino not only beat American Jim Ryun, the heavy favorite, he dominated the field, jumping to a huge early lead, and winning by 20 meters, the largest margin in the history of the event.

“Jim Ryun at the time was the world-record holder and the golden boy. It would be the equivalent of an African guy coming here and beating Michael Phelps in a couple of races. He broke all of the stereotypes,” said former Cornell track coach Kevin Thompson in a 2012 interview with the New York Times.

Keino was only the start. Naftali Temu won the gold at the 10,000, and Amos Biwott won gold in the 3,000 steeplechase. Wilson Kiprugut won silver in the 800 and Benjamin Kogo won silver in the 3,000 steeplechase. The team of Daniel Rudisha, Charles Asati, Naftali Bon and Munyoro Niamu won the 4x400 relay. Kip Keino also took home silver in the 5,000 and Naftali Temu won bronze.

Since 1968, Kenyans have won 86 medals in track and field, including 56 in the distance events.

According to Bukhala, 83 percent of Kenyan medal winners come from the Kalenjin tribe. In his article, he estimated Kenyan elite athletes run or walk between 8-12 kilometers per day five days a week when they are around 8 years old. This increases to 90 km per week as adolescents. He also stated Kenyan distance runners’ diets consist of about 10 percent protein, 13 percent fat and 77 percent carbs. The Kalenjin tribe members were deeply involved in cattle raiding, with raiders sometimes covering 50-60 km at a time. During a 2014 TED Talks presentation by author David Epstein, he said another major factor behind the dominance of the Kalenjin tribe members is their long legs are extremely thin. “The leg is like a pendulum, the longer and thinner it is at the extremity, the more energy-efficient it is to swing,” Epstein said.

Another reason for the Kalenjin tribe members’ domination may be the incredible pain they tolerate in an initiation ceremony. According to NPR some boys undergo a coming of age ceremony that includes them having to crawl mostly naked through a tunnel of African stinging nettles. They are then beaten on the bony part of the ankle. After this the knuckles are squeezed together and the formic acid from stinging nettles is wiped on the genitals. Early one morning, the boys are circumcised with a sharp stick and must remain silent and stoic the entire time. Journalist John Manners believe this ritual teaches the boys how to push through pain, a useful quality in long distance running.

The Kenyans and other East African countries are still dominating on the world level and this success can be directly traced to Kip Keino and the dominance of the other runners during the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

Max Bechtoldt is a senior journalism student at Arizona State University