Opinion: Events of 1968 brought purpose of disruptive protest into focus

Why this matters

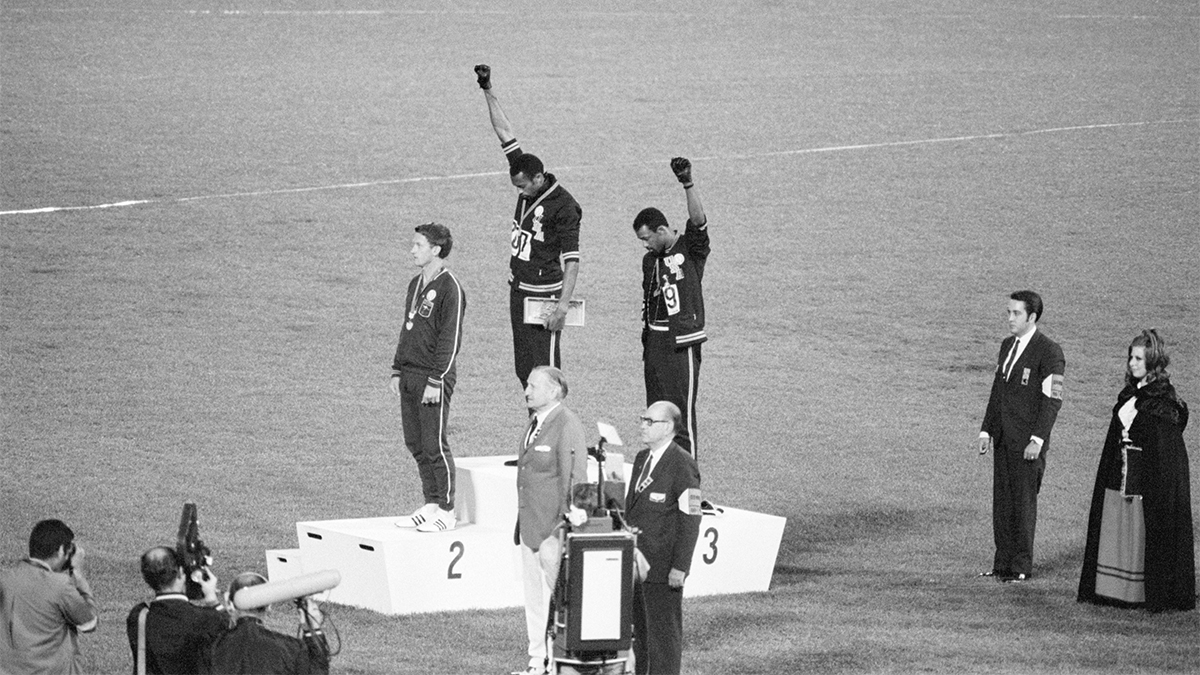

In 2018, Global Sport Matters and the Global Sport Institute commemorated the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium. We took a look back at the year from a global sporting perspective.

From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism. Read all the stories here.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the black-glove protest by John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the 1968 Mexico City Games. The protest was the culmination of the organizing efforts of the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

I was 13 years old and watching on a black and white Magnavox in our Los Angeles basement. As a 10-year-old, I had seen the Watts riots close up and have an everlasting memory of National Guard troops staging in the Crenshaw Shopping Center while my mother rushed me past a machine-gun-mounted Jeep to buy groceries at Vons Market.

My entire life had been lived in the background of the national fight for civil rights and major global events: bus boycotts, marches in Washington, the space race and the Cuban missile crisis. That was a black baby boomer coming of age chronology.

That summer, James Brown released “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Among all of the other changes of puberty, I was no longer Negro but black and swept up in a full-blown Black Power movement. The prism for me of the 1968 Olympic protest was a moment of pride and empowerment.

Much like many today in regards to NFL players kneeling to protest social justice issues, the anti-patriotism angle is not what I saw. Don’t get me wrong; I understand the analysis. I better see it as a conundrum: If you don’t protest in a way that causes discomfort, you won’t get the attention needed to highlight your issue.

Without a doubt there was no moment bigger than the Olympics in terms of attention. Also, the patriotic aura of the Olympics in 1968 was today’s environment on steroids. Looking back, there was no bigger, connected moment to protest the issues concerning the Olympic Project For Human Rights. Looking back, the only bigger moment could have been on the victory stand for the men’s 100 meters, the race that crowns the world’s fastest human. But the 200 was more than adequate.

Two things about the Olympics at that time that may not resonate so well with those who have not been longtime viewers of the games. First, many more Americans were track and field fans, and we knew these athletes the way people today know the stars of the NFL. The popularity of athletics was at a very different level. Second, the medal count made this whole show exciting, especially the prospect of the United States beating the USSR. This was a very patriotic event. It really was America versus the world. The bad guys were the communists, including the USSR and East Germany. You could also still find yourself rooting for American allies (yes, of the World War II vintage) such as Canada, Great Britain and Australia, when there was not a U.S. presence in a given race.

I believe leading up to the games the black community was suffering from a bit of disappointment because a proposed boycott by the black Olympians did not happen. Oddly, too, we were concerned that one of the few athletes who did boycott, Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) would lessen America’s chances of winning the men’s basketball gold medal. I recollect that concern as a glimmer of patriotism that no one was seeking to conceal. If we were there, I guess the logic went, we wanted the U.S. to win. A team without Kareem was not the dream team. It turned out not to matter. The basketball gold came back to the U.S.

They were there for a reason - to take a stand for human rightshttps://t.co/g7n7hij8y7@kenshropshire @GlobalSportASU @DrJohnCarlos @Real_TylerDare @andresDCmtz @UNAM_MX @Olympics @ASUSportsLawBiz @Cronkite_ASU pic.twitter.com/MgFxXWIrhb

— GlobalSport Matters (@GlobalSportMtrs) October 4, 2018

On Thursday, Oct. 17, 1968, we were back at Audubon Junior High School. Everybody in gym class wanted to be John Carlos or Tommie Smith. They were bad men. In our community, we knew what they were saying and that they were speaking for all of us. Fifty years ago it was Black Power versus patriotism, a framing that conflicts many of us today with the social justice protests of the NFL: “I believe in social justice, but that flag thing....”

The irony today is the best known athlete activist of the moment, Colin Kaepernick, now has a Nike advertising campaign. John Carlos, Tommie Smith and even Peter Norman spent years trying to get their lives back on track after that protest. None of them ever had a major apparel deal.

Like the long road of societal acceptance rehab that brought anti-war protestor Muhammad Ali to the forefront of athlete heroes, the road Smith and Carlos have taken took a turn upward as well. That time and distance formula provided clarity of impact and intent. Overall, 50 years later, this is a day of celebration where the purpose of the protest is much more clearly grasped by all than it was in the moment commandeered to get our attention. More of us can see it through the eyes of a 13-year-old praying for an equal chance and respect in the world ahead.

Kenneth L. Shropshire is the CEO of the Global Sport Institute and adidas Distinguished Professor of Global Sport as Arizona State University and Endowed Professor Emeritus at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Among his 13 books is Sport Matters: Leadership Power and the Quest for Respect in Sports