Global student protests put 1968 Mexico City Games on edge

As we commemorate the 50th anniversary of the seminal moment of the Mexico City Games, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised a black-gloved fist from the medals podium, GlobalSport Matters looks back at the year from a global sporting perspective. From the World Series helping a wounded Detroit heal to athletic innovations that trace their origins to those Olympics, 1968 served as a critical pivot point in the role sports plays in society and introduced the modern era of athlete activism.

The year 1968 remains one of the most impactful in the campaign for civil rights and the fight for equality around the world.

In a year of constant turmoil, students stood up against police violence or for education and social equality through public protests. However, activists and students were met with hostility, arrest, injury and death at the hands of their governments. As movements started in major countries around the world — notably France, West Germany and the United States — students in Mexico City used the platform provided by the upcoming Olympic Games to demonstrate their resistance against violence and repression.

The beginning of the student resistance movement began in West Germany in 1966. The student movement challenged its country’s government for “undemocratic reforms regarding universities and the right to use military force,” as well as systemic police brutality, press censorship and aggressive power in the government, according to Global Nonviolent Action Database.

At the time, Benno Ohnesorg was a 26-year-old student attended his first and last protest during the Shah of Iran’s visit to West Berlin on June 2, 1967. A 2015 article for the German edition of The Local, a digital news site, described how due to the Shah’s dictatorial rule over Iran, “the protests turned into violent chaos when police and Iranian agents started attacking peaceful protests.” During the violence, an unarmed Ohnesorg was shot and killed by a police sergeant. The article states that “for the student movement, the murder of a peaceful, unarmed protest was the perfect example of the kind of authoritarian state against which they were demonstrating.”

In response, the German student movement galvanized not only against the death of Ohnesorg, but also the undemocratic influence of East Germany on West Germany. Germans “were enraged that former Nazis held powerful positions in society,” according to DW. Worried that West Germany could be reverting back to the National Socialist ways with groups such as the Red Army Faction, students demanded that West Germany would change more toward democracy, reducing the right-wing influence, and reforming student curriculum, according to Revoly.com. Students opposed the newly proposed German Emergency Acts that allowed the German soldiers to intervene in all acts of crisis and placed limitations on privacy, “confidentiality of telecommunication and of postal communication,” and limited “freedom of movement” and affected one’s “occupational freedom.” The German student movement started to form, led by Socialist Student Union spokesperson Rudi Dutschke. Dutschke organized marches, “led sit-ins, hunger strikes and protest demonstrations from his base at West Berlin Free University,” according to Dutschke’s 1979 obituary in the Washington Post. Dutschke was nearly assassinated on April 11, 1968, initially surviving brain damage from the bullets but died 11 years later from the injury.

Throughout West German cities, according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, students gathered in the thousands. On May 11 1968, “students, schoolchildren, and members of workers’ union formed a group of 80,000 people who demonstrated in the capital Bonn against the emergency legislature,” according to Revolvy.com. Failing to stop the passing of the Emergency Acts, the student movement started to fall apart and soon dissipated. It wasn’t until 1972 when the german government passed a “radical decree” that prevented people who believed in undemocratic principles.

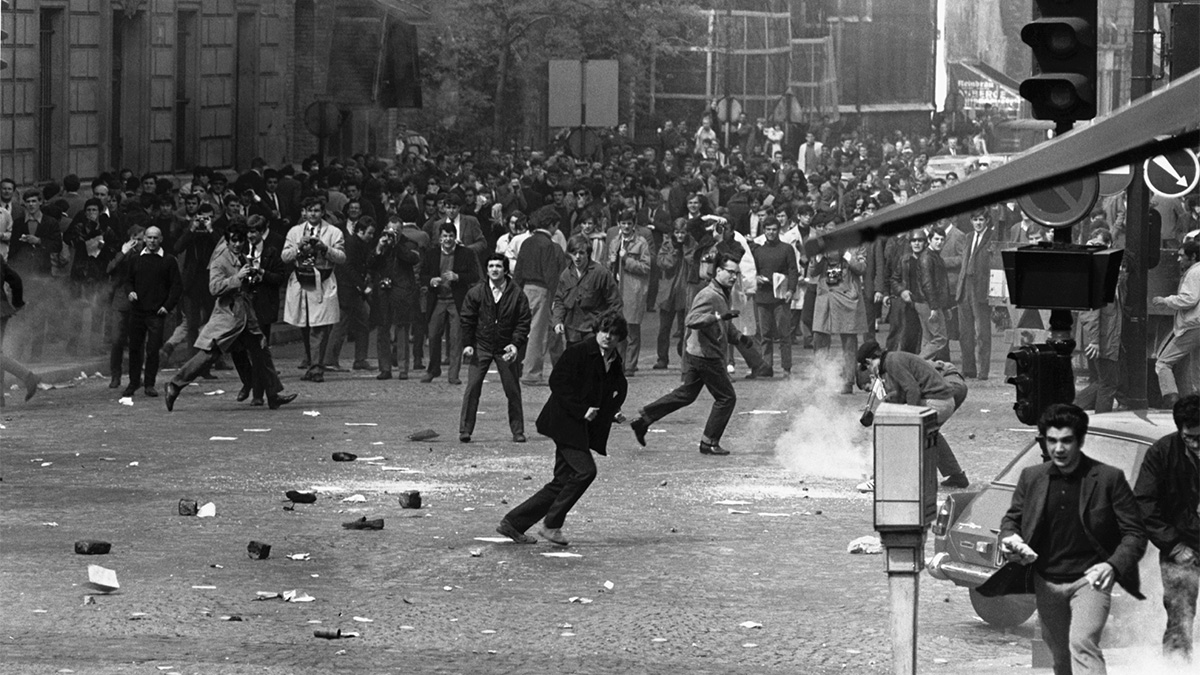

Echoing events in Germany, student activists in France called for reform in education, holding government officials accountable for their actions, and equality and justice from the police. An entry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica on the events of May 1968, describes a France navigating “an era of international ‘youth culture,’ yet French society remained autocratic, hierarchical and tradition-bound.”

After a series of protests and conflicts between the students and authorities at the University of Paris at Nanterre, the administration shut down the university. Subsequently, “Nanterre students came together in the centre of Paris and after continual harassment and over 500 arrests, erupted into five hours of rioting with police.” On May 7, “a 50,000 strong march against police brutality [turned] into a daylong battle through the streets and alleys of Paris’ Latin Quarter,” according to Libcom.org. Throughout the month of May, protests increased in number and grew in size across France. On May 30, French Prime Minister Charles De Gaulle announced “there would be new legislative elections unless the people were prevented from voting by ‘intimidation, intoxication and tyranny,” according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database.

Meanwhile, in early March 1968, a teacher named Sal Castro led the first protest in a series of student walkouts known as The Chicano Blowouts in East Los Angeles, California. In the book “Blowout! Sal Castro and the Chicano Struggle for Educational Justice,” Michael T. Garciá and Castro wrote the latter “challenged the status quo and the practices of unequal and segregated Mexican schools” by guiding several schools in organized walkouts to bring light to an unjustified racial hierarchy amongst Mexican Americans, specifically people of Chicano heritage.

In the book, Castro wrote “public schools are unequal and segregated based largely on race and class.” Castro recognized how, unfairly, schools with a majority of Latino students had “inferior and poor conditions associated with these schools.” However, Castro was concerned how “such conditions condemned Chicano students to a limited future as part of the recycled pool of Mexican cheap and unskilled labor.” Castro and other leaders in the community, such as David Sanchez, told the Los Angeles Times that “after the walkouts, no one could deny that we were ready to go to prison if necessary for what we believed.” The Los Angeles Times wrote the walkouts were “the first act of mass militancy by Mexican Americans in modern California history set a tone for activism across the southwest.”

Following global protests from student activists in Europe and in the U.S., students in Mexico City stood up with similar goals of equality. However, on October 2 — 10 days ahead of the opening ceremonies of the 1968 Olympics — “hundreds of people lay dead or wounded, as army and police forces seized surviving protestors and dragged them away,” according to a 1998 entry from The National Security Archives at George Washington University.

The initial spark that led to the student protests was on July 22, 1968. A fight between students from the Polytechnic and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, soon clashing with the riot police that led to injuries and arrests, according to “The Student Movement of 1968 and the Mexican Press” by Claire Brewster. In retaliation, students in Mexico City started to protest the police and the schools. Following days of rioting, Mexican President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and Secretary of the Interior Luís Echeverría orchestrated an assault on the students’ headquarters, intending to halt the growing unrest. According to the El Universal newspaper in Mexico: “Echeverría then requested military intervention, arguing that the local police department wasn’t able to suppress the students, who allegedly altered the city’s peace. Echeverría was given the green light to order a siege of the school.”

In the early morning hours of July 30, paratroopers and rifleman prepared to enter the San Ildefonso High School — which students were using a staging compound — the military used a bazooka to destroy a 300-year-old carved colonial door and gain entry. As a result of the operation, approximately 1,000 students were either injured or taken into custody.

Shortly after the attack on the school, “students decided to organize and protest the violence exerted by the riot police,” according to a 2008 report on the NPR program “All Things Considered,” and “over the following months, Mexico City witnessed a series of student protests and rallies against repression and violence.” In the days leading to the Tlatelolco massacre, students were hoping their government would work with them to end unjustified police violence.

With the 1968 Olympics scheduled to take place just miles from Three Cultures Square, the site of the main protests, the students had hoped to use media coverage of the Olympics as a platform for their movement. However, Ordaz feared protesters would infringe on the one-party system’s power with their demands, which included:

- Releasing all political prisoners

- Dismissing the chief/assistant chief to the police force

- Disbanding the riot police

- Revoking Articles 145 and 145A that protected the imprisonment of government critics

- Compensation for victims of police brutality

- Prosecution of guilty state security forces for damaged and destroyed property.

On the morning of Oct. 2, more than 10,000 students and protesters gathered at the square in the Tlatelolco neighborhood in Mexico City. John Rodda, a reporter for The Guardian assigned to cover the games, described witnessing the student riots and the massacre.

Rodda wrote “as the crowd filed into the square, there were armed police on the balcony.” At first, he recalled there was a lot of resentment by students toward the police, but the police remained calm. Students conducted several speeches and walked around the square with large banners, “after the speaking had been going on for between 30-45 minutes during which time two helicopters had circled overhead. There were suddenly two green lights which shot into the air from behind the church,” Rodda said. “At that moment, there appeared three, four, five or six men with revolvers indicating to us to get on the floor. They’re just going to shoot us down.”

Rodda explained bullets were flying overhead as he tried to take shelter, “the worst moment came when someone with a machine gun high up was spraying bullets down, and the firing line was catching the edge of the walls and sending sparks up and sprinkling the corner where I was covered in cement and concrete chips.”

Protesters stayed for several hours voicing their feelings and as the gathering started to end, soldiers arrived to capture the movement’s leaders. Instead, they were greeted by gunshots from the buildings surrounding the square, according to NPR. The soldiers opened fire onto the crowd for nearly two hours, resulting in “the number of civilian casualties reported [had] ranged between four and 3,000,” according to NPR.

After decades of silence, Echeverría was interviewed by CNN in 1998 and said: “These kids were not provocateurs. The majority were sons and daughters of workers, farmers and unemployed people.” He blamed Ordaz, claiming “the army is obligated to respond to only one man.”

Regardless of who made the final decision, the act of Mexico’s government gunning down student protesters exposed how opposed that government was to the ideas of democracy and social reform, which were, ironically, principles the games were meant to highlight.

In the midst of the opening ceremonies, the Mexican government essentially covered up the events at Tlatelolco. Lance Wyman, the designer of the Olympic logo, said: “It didn’t affect the games that much on the surface. I think there was kind of an agreement with the news organizations all over the world to hush it up so that it wouldn’t affect the games.”

According to a report by the BBC, “the death toll remains uncertain. Some say it runs into thousands, although it is thought to be between 200 and 300. Eyewitnesses said bodies were removed from the scene throughout the night.” The article reported more than 500 were arrested, yet those numbers also remain up for debate. The Mexican government’s official report claimed a death toll of 30.

Despite the violence, the Games proceeded normally.

As Tim Wendel, author of “Summer of ‘68: The Season That Changed Baseball and America Forever,” wrote: “The show must go on. What we see is the last vestige of old-style power and something had to change, what was being lost was the individual.”

Mexico City proceeded with the games with hopes there would be no political/social justice interference. However, athletes such as Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith, Czechoslovak Vera Caslavska and others staged various forms of protest to shed light on social equality in their countries throughout the Olympics.

With so many protests and so much public strife surrounding social issues and government repression around the world in one calendar year, the riots by Mexican students were overshadowed but certainly not forgotten.

Tyler Dare is a senior journalism student at Arizona State University