MLB pursuing measures to stop PED intake internationally

Why this matters

Latin America is an important talent pipeline for MLB, but if prospects aren't clean while trying to make it to the big leagues, they may take away their only shot at success

Michael Pineda #35 of the Minnesota Twins delivers a pitch against the Cleveland Indians during the game on September 6, 2019 at Target Field in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Indians defeated the Twins 6-2 in eleven innings. (Photo by Hannah Foslien/Getty Images)

Major League Baseball has pursued ways for its athletes – born in the U.S. or internationally – to reach their peak performance without the use of performance-enhancing drugs. In 2018, MLB worked out a deal with Latin American trainers to try to prevent the use of PEDs among amateur players early on.

Through MLB’s Joint Drug Prevention and Treatment Program, the organization monitors players’ drug testing in-season and out-of-season. If players are found in violation through a positive test for these banned substances, possession of or intent to distribute – they will face suspensions ranging from 80 games to the 212-game suspension that Alex Rodriguez faced back in 2014.

“Our hope here is that the adjustments that we’ve made do inevitably get that number to zero,” the current executive director of the MLB Player Association, Tony Clark, told ESPN in 2014. “I hope that players make the right decision that are best for them, for their careers and for the integrity of the game.”

Over the past year, MLB was able to monitor over 1,100 prospects from the Dominican Republic and 600 participants from Venezuela. The training staff also increased in the first 12 months, with a jump from 60 to 73 trainers. Because the program’s potential continues to remain high, MLB officials remain excited for what these amateur players have to offer.

“Avoid performance-enhancing drugs. You cannot be successful over the long haul with the use of these drugs. They’re bad for you, and they ultimately will be bad for your career,” Baseball Commissioner Robert Manfred said to MLB.com.

Prominent Latin American players like Minnesota Twins pitcher Michael Pineda and New York Mets second baseman Robinson Cano are among the 65 percent of players suspended for failed drug tests who are from Latin America, according to BaseballAlamanc.com, causing concern among those in the league. Just in the minor leagues alone, there were hundreds of Latin American baseball players who were disciplined from the 2012 to 2019 seasons, according to MiLB.com.

According to the MayoClinic, what is considered a PED ranges among anabolic steroids, human growth hormones and stimulants. Even though use can be detrimental to their own health, baseball players take these various drugs in an attempt to gain muscle, improve performance and be able to train harder with quicker recovery time, according to FoxNews.com.

“You can cycle it, so you have moments of medicine in you, so aggressive training and medicine enhance that training,” Dr. Robert Truax, a family and sports practitioner from University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland told FoxNews.com. “Then they get off of it, and hopefully their training without the medicine is a little bit better.”

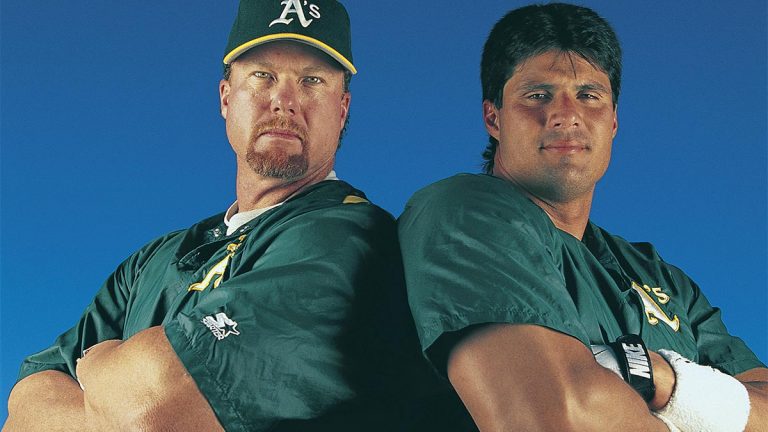

Performance enhancing drugs and MLB have had a tumultuous relationship through the past few decades. While the 1990s – the era of the Bash Brothers, Barry Bonds, Brady Anderson, etc. – was a time of bulky batters and fat stats, MLB cracked down on PED use after the BALCO scandal.

MLB is looking to root out PED use in Latin American academies and players through this training program, according to APNews.com. This has led to the push for standardizing drug testing for these international prospects.

“In an effort to standardize this process, and to ensure that all drug testing of international prospects is conducted efficiently and in accordance with applicable local laws and MLB policies,” Vice President of Drug, Health and Safety Programs at MLB Jon Coyles said to Forbes.com.

Many people in the baseball community see that the more MLB gets involved, the more places like the Dominican Republic in Latin America will be capable of not stepping over the line.

“MLB could do wonders in this country if it worked harder to make things better,” Homero LaJara, a buscone, or trainer, who runs a Dominican baseball academy for boys competing for professional contracts, told the Boston Globe. “It would be a win for MLB and the United States of America because they would be getting players who are educated, who aren’t changing their birthdates and identities, and who aren’t pumped up with steroids.”

Corey Kirk is a masters sports journalism student at Arizona State University