Kickoff fair catch rule meant to increase safety, but critics not so sure

In Facebook terms, the relationship between Jordan Bernstine and special teams is … complicated.

Now he fears the beast could become an endangered species.

“My mindset is [kickoffs] are more a part of the game,” said Bernstine, the former University of Iowa and NFL defensive back and kick returner. “I didn’t get hurt because I was running into a guy too hard.”

As a Parade All-American at Des Moines Lincoln High School, Bernstine ran three kickoffs back for touchdowns. In 2011, he ranked among the Big Ten’s best in kick return yardage (No. 8, 713 yards) and kick return average (No. 9, 23.8 per runback).

Speed got him on the field. Speed got him drafted — in the seventh round by Washington in the spring of 2012. Speed got him on the active roster as a rookie in Week 1.

But as the kicking game gave, so did it take away months — or years — of Bernstine’s football prime.

An injury sustained while serving as a gunner on the Hawkeyes’ punt team ruined the middle years of his Iowa tenure. In Washington’s 2012 NFL season-opener at New Orleans, Bernstine was on kick coverage in the fourth quarter when a Saints blocker engaged him and locked up his arms.

“I was looking over his shoulder for the ball carrier, and two guys that were behind me, they fell into the back of my leg,” Bernstine recalled. “Just an awkward fall.”

Awkward and awful. The rookie defensive back tore the anterior cruciate ligament, the medial collateral ligament, the posterior cruciate ligament and patella tendon. His right knee and pro football career simultaneously were blown to bits.

“My knee was basically broke, so there was definitely pain,” Bernstine recalled. “I couldn’t put any weight on it. I was even still positive [when] it happened, thinking, ‘Maybe it’s just this or that.’ [They said], ‘No, no, it’s all that.’ It was just kind of a freak accident.”

[beauty_quote quote='"...the changes are seen as the institutions just trying to protect themselves from lawsuits. This cynicism is probably well-justified." - Shawn Klein, Arizona State University professor specializing in philosophy of sport ']

Bernstine was cut by Washington the next July and never again appeared in an NFL regular-season game.

At 29, he is an owner and coach at Ground Up Sports Performance in Colorado Springs, Colo., a football casualty who refuses to play the victim card.

But when anyone brings up the new NCAA rule that will allow kick returners the option of signaling for a fair catch and giving his team the ball at the 25-yard line, a safety gambit making its debut this fall, that’s when Bernstine starts to cringe.

“It’s a split-second decision that guys have to make,” Bernstine said of special teams contact. “‘Do I go high? Hit them there?’ I’ve been on both sides of that.

“Any time there can be kick returns or punt returns and all that, that’s just another opportunity to make a play. In my mind, it’s almost like they’re trying to take out people’s opportunity to make a play.”

Move to avoid head injuries

While football purists view the kickoff as a sacred cow, the NCAA has concerns with the rate of potential collisions — especially collisions involving the head — at top speed.

In the summer of 2016, the governing body gave the Ivy League the green light to move its kickoffs up to the 40-yard line in conference games after data showed 23.4 percent of all concussions sustained in the game occurred on kickoffs despite kickoffs accounting for only 5.8 percent of all plays. An NFL study of the past three seasons revealed concussions were five times more likely to happen on a kickoff than on any other type of play.

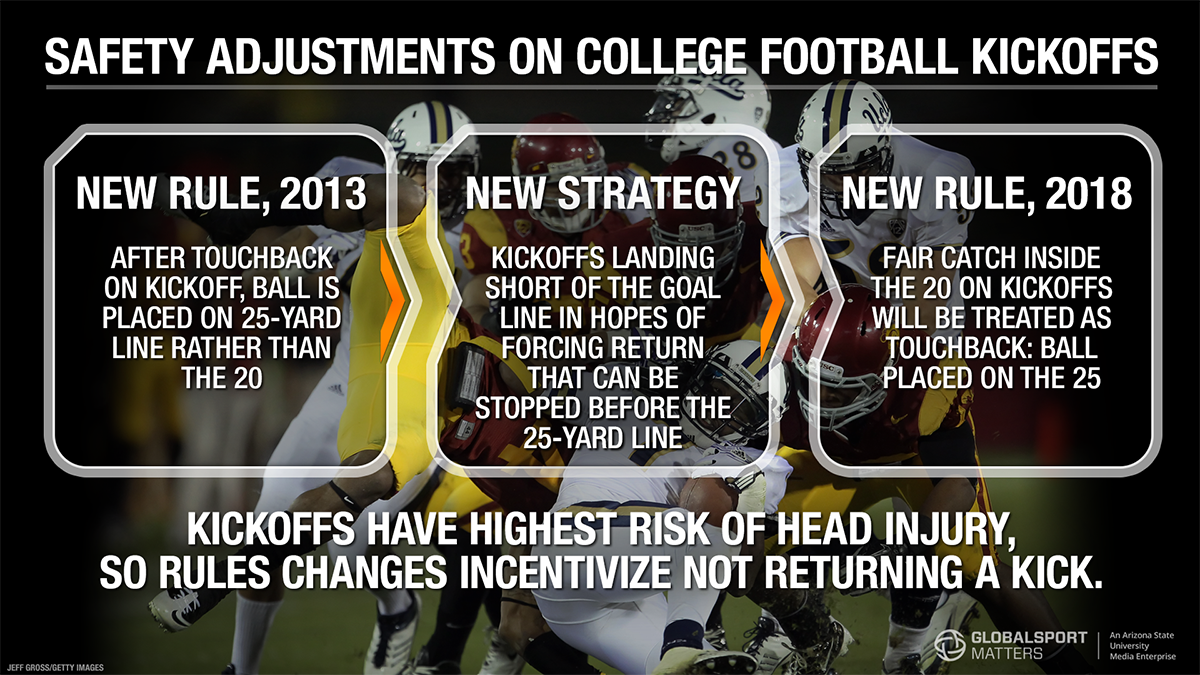

The fair-catch rule is the third major change in the past decade to one of the college game’s foundational plays. In 2012, the NCAA moved the starting point on touchbacks from the 20-yard line to the 25 while also moving the kickoff spot from the 30 to the 35. Two years earlier, wedge blocking — a grouping of three or more players in close quarters — was banned.

In the fall of 2017, 43.2 percent — almost half — of kickoffs in Football Bowl Subdivision contests were touchbacks. Of the 8,999 kickoffs last season, 61 — 0.68 percent — were run back for touchdowns.

Which begs the questions: Are all these changes to kickoffs and their returns really making the game safer, or is the NCAA sacrificing the kickoff for a negligible impact?

Which begs the questions: Are all these changes to kickoffs and their returns really making the game safer, or is the NCAA sacrificing the kickoff for a negligible impact?

“Some of what is behind this gripe is the sense that the rule changes are not really about player safety at all,” said Arizona State professor Shawn Klein, whose specialties include the philosophy of sport. “Instead, the changes are seen as the institutions just trying to protect themselves from lawsuits. This cynicism is probably well-justified.

“Still, there is a concern that inherent violent nature of the game is being undermined by these rule changes and that this change is bad. Football, by design, is a dangerous and violent game and that is a part of what attracts people to it. There is, I’d argue, a good case to be made for the importance and value of dangerous sports in our lives — both as participants and fans. If that case can be made, then there is a legitimate concern if football is made no more dangerous than, say, golf.”

While the principle may be disagreed with, the data is more difficult to dispute. During Ivy League conference play from 2013-2015, kick returns accounted for an average of six concussions each season. After kickoffs were moved from the 35 to the 40, the Ivy reported no concussions were sustained on kick returns in 2016. Member schools that year averaged 2.4 touchbacks per game in non-conference contests and nearly doubled that rate, 4.5, in conference games.

“There’s been a progressive effort by the NCAA — and the NFL — to improve player safety by revising kickoff rules to try to ensure more touchbacks,” noted Pam Sailors, a professor at Missouri State and author of “Personal Foul: An Evaluation of the Moral Status of American Football,” published in Journal of the Philosophy of Sport in 2015. “This does remove certain strategies, like trying to pin an opponent deep with a sky-high kick, and certain exciting plays, like long kickoff returns. Whether that changes the game too much depends on how essential you consider those plays to be. My own view is that change is an inevitable, and generally desirable, part of every sport.

“I agree with those who suggest that eventually the kickoff will be eliminated from the game entirely. Instead, we’ll see something like the NFL has used in the Pro Bowl, where every offensive drive after scores begins on the 25-yard line — and new strategies will be developed to take advantage of the change.”

No substantial reductions in injuries

Limiting live kick returns means some football careers — especially those of skill-position players, return men, the Bernstines of the present and future — may be extended or saved. Yet some experts on football and head trauma contend the sport’s greater evil is the effect repeated head shots have on development of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, and not the viral — and more violent — hits associated with special teams.

“That sacrifice, that’s wonderful,” said Robert Stern, a professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Boston University and the director of clinical research for the school’s Alzheimer’s disease and CTE centers. “But so much of the discussions about brain trauma in football at all levels stems from the long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma and, in particular, CTE. And it’s unlikely that the rule change will have that big of an impact, so to speak, on long-term problems.

“There really needs to be greater focus in reducing the overall exposure to these hits. Not just the big ones that make for great TV, and not just the ones that result in symptomatic concussions.”

The scrum in the box doesn’t make for great TV. Yet studies report offensive line is the most susceptible unit to the long-term effects of CTE because the nature of the position requires continual blows — subconcussive impacts — to the head on almost every snap.

“More flexibility on kickoff fair catches will move the needle slightly to make the game safer, but it isn’t going to result in a major reduction in short-term injuries,” said Molly Ott, a professor at Arizona State with an expertise in community sports. “Nor will it impact the longer-term risk of brain disease that football players face.

“Although a few athletes will be less likely to experience injuries, the rule change will not have a substantial effect on total injuries across the population of football players. This is because there are fewer special teams players, and they are not on the field as frequently as other positions.”

[beauty_quote quote='“The evidence is growing as such that it’s pretty silly for people to talk about the ‘wussification’ of football if they understand that the brain is our most important organ." - Robert Stern, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Boston University ']

If NCAA and NFL officials want to get serious about reducing the risk for long-term brain issues such as CTE, Stern said, they should consider fewer full-contact practices, where repeated blows to the head aren’t a part of public consumption. He has pondered what would happen if the three-point stance were abolished.

“Linemen are starting across the line of scrimmage with their heads down, ready to pounce,” Stern said. “They don’t look up, and they hit their heads against the opposing lineman in almost every play of every game and in every practice. And if you got rid of the three-point stance, there may be some reduction of those constant hits.”

Stern doesn’t fear blasphemy in football — or the lords of the game. In 2014, he filed a declaration in opposition to the NFL’s settlement of a CTE-related lawsuit filed by former players and accused commissioner Roger Goodell of inheriting a “cover-up” from predecessor Paul Tagliabue.

“I’ve been told on more than one occasion that I’m responsible for ruining the game of football,” Stern said with a chuckle.

“I know a lot of former football players that played in the pros, [and] they’re sportscasters and they’re [saying] that it’s the same argument that, ‘My aunt Cecilia smoked like a chimney but she’s a 90-year-old and she doesn’t have lung cancer.’

“The evidence is growing as such that it’s pretty silly for people to talk about the ‘wussification’ of football if they understand that the brain is our most important organ. And it’s inside that hard skull, surrounded by spinal fluid. And the helmet, no matter how big and strong it is, doesn’t prevent the brain suddenly jolting back and forth whenever that helmet is hit. In fact, that helmet makes it so you can’t feel the pain that one is supposed to feel in order to avoid getting hurt in the future.”

If the new fair catch rule had been around a decade ago, Bernstine might still be playing.

“I don’t really buy that,” Bernstine said. “Injuries are a part of the game. And it can happen anytime you’re running, stopping and cutting. It just happened [while there were] more guys falling, and stuff like that.

“To be honest, I’m kind of interested to see how it goes. I know if I were back there, I would still be trying to get further with my legs — no fair catch or any of that. They’d have had to hold me in the end zone.”

Sean Keeler has written for several media outlets, including FOX Sports, The Guardian, American Sports Network, and Cox Media's Land of 10 and SEC Country verticals. You can follow him on Twitter @SeanKeeler

Related Articles

Baseline concussion testing keeps athletes game ready

New research, technology aimed at minimizing concussions

"Put me back in coach" showcases injury decisions for high school football coaches