Baseline concussion testing keeps athletes game ready

In the last decade, sports-related concussions have become a hot topic for athletes of all ages. As student-athletes get ready to return to fall practice, baseline concussion testing is part of the diagnostic assessments they will undergo to return to the field.

Many physician researchers who specialize in concussion research agree that there is still a lot about concussion medicine and the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) that is unknown. What we do know is the prevalence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been steadily increasing over the last few decades and sports-related concussions can no longer be swept aside. Skeptics may argue prevalence is increasing because diagnostic methods have become more sensitive, but improved assessment and diagnosis reduce the number of athletes who slip through the cracks, making it safer for athletes in both the short and long term. In recognition of the impact that concussions may have on individual athletes and the sport industry as a whole, organized sports at the high school, collegiate and professional levels are taking steps to enhance concussion detection and care.

Concussion management begins with preparticipation baseline testing. Testing can include a variety of measures that are then used postconcussion as a comparison to help diagnose and manage the return to play (RTP) plan.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a multimodal approach in baseline testing that includes a medical history; balance test; cognitive function assessment, including concentration and memory; and standardized neuropsychological tests. The NCAA released the most updated Concussion Diagnosis and Management Best Practices in 2017 to serve as a recommended standard protocol for athletic departments and sports medicine staff to implement on their campuses. Recommendations include concussion education, multimodal baseline concussion assessment, recognition and diagnosis and postconcussion management by a physician, including clinical evaluation and gradual progression to RTP.

Some state governments and professional sports societies have also published similar guidelines and recommendations to better control concussion management. This movement is encouraging, but most of the published statements are recommendations that are not stringently followed or regulated. Therefore, it is up to the athlete or parents to be aware of the various assessments and advocate for comprehensive assessment and medical management within their team or organization.

Many baseline testing systems are available, and they include different aspects of different neurocognitive functions. Examples include the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT5), Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT), the King-Devick concussion test in association with Mayo Clinic and the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS).

The SCAT5 is a comprehensive symptom and cognitive assessment that examines observable and reported symptoms, orientation, responsiveness, memory and concentration. It is known in sports as the “sideline concussion test,” but its creators recommend SCAT5 be used for patients older than 13 in conjunction with further clinical assessment and workup and not be utilized as the only method to inform diagnosis or RTP plan. For patients age 12 or younger, the Child SCAT5 assesses the same measures.

The King-Devick (K-D) test is gaining traction as a sideline assessment tool for concussions. The K-D test is a visual performance test that can be easily administered on the sidelines. It requires an athlete to read single-digit numbers displayed on an iPad screen or cards. After suspected head trauma, the athlete is given the test, which takes about two minutes. The results are compared to a baseline test administered previously. The test measures the speed of rapid number naming and captures impairment of eye movements, attention, language and other correlates of suboptimal brain function.

Literature indicates the K-D test may be useful in identifying concussions. Any worsening of baseline at the time of injury indicates a five times greater risk of concussion.

The BESS assessment is a balance test that requires athletes to balance on single-leg and tandem stances. It is included in the SCAT5 but is often used separately.

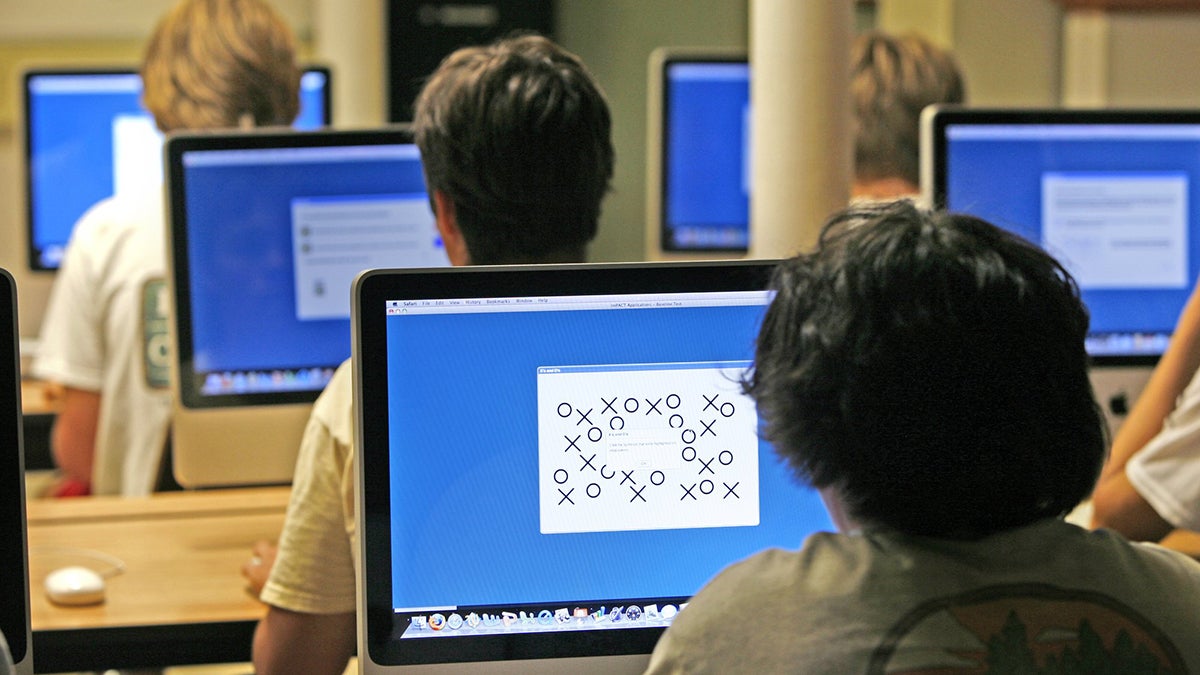

ImPACT is typically a computerized exam comprised of six modules used to generate scores in visual memory, verbal memory, visual motor speed and reaction time. The assessment’s test-retest reliability has been debated, but it is generally accepted as a valid tool for baseline cognitive assessment.

Even when administered by professionals under controlled conditions and executed by athletes using their full potential, studies have shown that factors such as sex, age, race, prior or current diagnosis of ADHD, reduced sleep and strenuous exercise prior to testing can significantly impact performance on baseline testing.

Another issue that sports organizations face in utilizing baseline testing as a valid comparison is the phenomenon of sandbagging, or purposefully underperforming. Athletes have reduced their efforts and strategically missed points on assessments so a lower baseline score may allow them to return to “normal” sooner and get them back into their activity. In 2011, NFL quarterback, Peyton Manning admitted to underperformance, stating “After a concussion, you take the same test and if you do worse than you did on the first test, you can't play. So I just try to do badly on the first test." While honesty is appreciated, this kind of statement from a person of his influence in professional football sets an unacceptable example to younger generations of athletes who may choose to mimic this behavior so they, too, can play through a concussion.

Interestingly, one study examined how easy it is to actually fake the ImPACT and found that only 11 percent of the 75 participants instructed to intentionally perform low without being flagged as an invalid tester were able to do so successfully. Those that were successful didn’t differ in demographics, concussion history or sport played compared to those that failed. The main difference was test strategy to make more “natural errors,” which were easier to plan if the participant had taken the ImPACT prior to this experience. So, sandbagging may not be as simple as it sounds, but teams should be on the lookout for athletes who may be intentionally underperforming or withholding effort during examination.

These assessments exist because they can be very helpful in assessing a person’s symptoms and cognitive deficits postconcussion and help determine when they’re in cognitive recovery and can begin the gradual reintroduction into activity. However, the circumstances that can affect testing and the inherent flaws and limitations are equally important to consider. These tools are not diagnostic by themselves, and clinical workup by a concussion specialist after any suspicion of concussion is imperative. These physicians are trained to interpret the assessments for the individual and take the individual’s background and medical history into account during evaluation.

With all the buzz in the media surrounding concussions and CTE, comprehensive evidenced-based education for athletic departments, sports teams, athletes and families could be very beneficial in calming some fears while stressing the importance of accurate testing and reporting to enhance concussion management and prolong cognitive health.

For more information on sports-related concussions and TBI, visit www.cdc.gov/headsup.

Brittany Foley is a first-year medical student at Mayo Clinic School of Medicine in Arizona. She is part of the sports medicine research team at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Donald Dulle is a physician assistant in Orthopedic Sports Medicine at Mayo Clinic Arizona. He is part of the sports medicine research team under the supervision of Dr. Anikar Chhabra.

Dr. Anikar Chhabra is a national expert in the field of orthopedic surgery and sports medicine and the director of Sports Medicine at Mayo Clinic Arizona. He graduated cum laude from Harvard University with a B.A. in Economics. While at Harvard, he was a four-year varsity basketball letter winner. Dr. Chhabra completed his medical school and residency at the University of Virginia, and his Sports Medicine Fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh. He currently is an orthopedic consultant for Arizona State University.

Related Articles

Scientists hunt for a test to diagnose chronic brain injury in living people