Nature of the game: Is cheating just part of baseball's DNA?

Editor’s Note: This story is being highlighted in Global Sport Matters’ Best of 2019.

Eduardo Perez is a perfect example of a baseball player who learned how to get an edge early in his major league career.

While taking bunting practice during spring training in 1992, Perez fouled a pitch into his left eye, creating permanent damage.

“I couldn’t see,” Perez told GlobalSport Matters. “I had a tear in the pupil and the eye is permanently dilated. With that tear there I also had a hole in the retina. I had internal bleeding. That’s why I could not see. It was just white because of the blood that was in there.”

Perez, a right-handed hitter whose left eye is dominant (because it is the side he faces the pitcher), played 13 seasons in the big leagues with about 40 percent of his vision.

How did he do it?

He compensated for that vision loss by knowing what the pitcher was going to throw and when he was going to throw it. Glove open on a curveball, closed on a fastball. Hands positioned in a certain way. The tipoffs were many.

The art of reading how pitchers tip their pitches and stealing opposing teams’ signs is as old as the game itself. It’s legal today as long as teams don’t try to use external technology to do it.

The fact it still exists became apparent for many as the Boston Red Sox rampaged through the 2018 postseason, winning the World Series in five games over the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Second time in postseason a team has detected Machado stealing signs from second base. The Brewers noticed same thing during the NLCS, according to a previous story from @ByRobertMurray. Perfectly legal and part of the game, as long as it is done without video assistance. https://t.co/5F5G0m8DC8

— Ken Rosenthal (@Ken_Rosenthal) October 26, 2018

The Red Sox and the Cleveland Indians complained the Houston Astros, their opponents during the first two rounds of the American League playoffs, were trying to steal signs. A club employee was seen taking pictures near the photographers’ well opposite the Boston and Cleveland dugouts. Major League Baseball investigated and exonerated the Astros.

“A thorough investigation concluded that an Astros employee was monitoring the field to ensure that the opposing club wasn’t violating any rules,” Major League Baseball said in statement last month.

[beauty_quote quote='“A thorough investigation concluded that an Astros employee was monitoring the field to ensure that the opposing club wasn’t violating any rules." - Major League Baseball statement after claims a Houston employee was aiming a cell phone into opponents dugouts']The Astros were neither fined nor sanctioned.

“We consider the matter closed,” MLB concluded. The Astros defeated the Indians in an AL Division Series, but lost to the Red Sox in the AL Championship Series.

During the World Series, the Red Sox complained Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop Manny Machado was trying to steal the catcher’s signs while standing near second base. It was one of many complaints teams had about Machado during the postseason. Boston cured that one by keeping Machado off second base.

Though the Red Sox did most of the complaining about cheating this postseason, the focus on all that skullduggery was simply one factor: Red Sox rookie manager Alex Cora.

“Everyone is paranoid of Alex,” Perez said. “I think a lot has to do with that and his reputation. He has a crew over there that’s brilliant at that. He has Ron Roenicke as a coach, who was known for that as a player. They know one thing: Alex wants to win, and he’s going to uncover or look under any rock possible to give his team an edge.”

Stealing signs

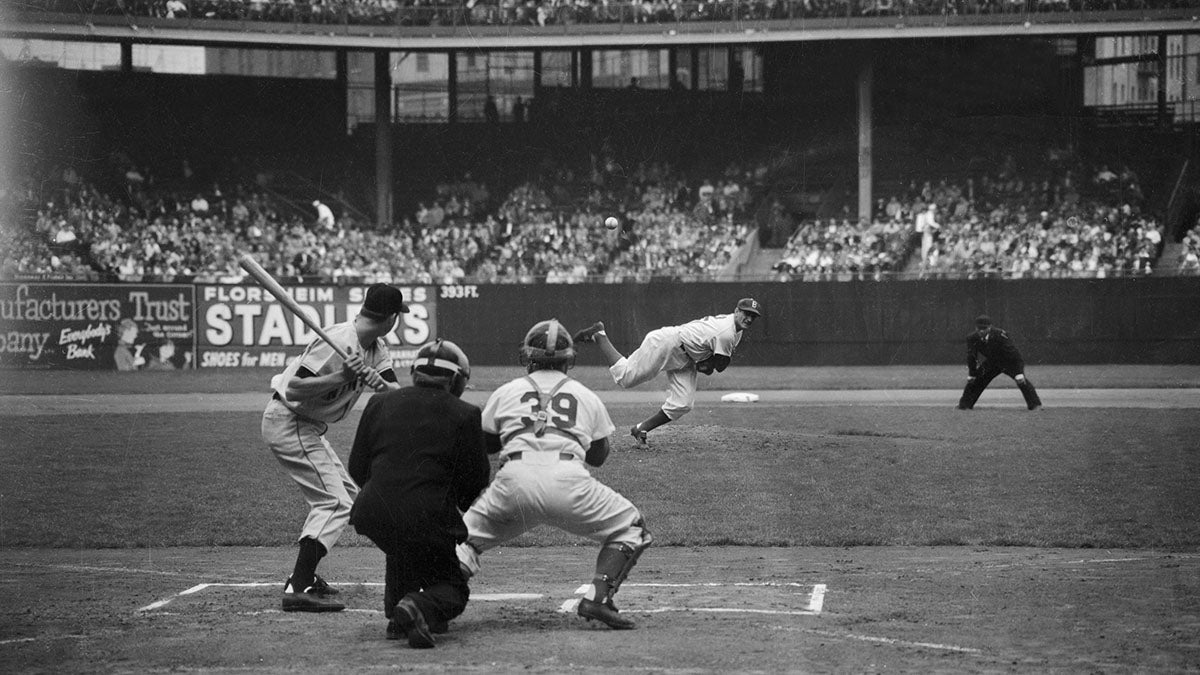

Teams have been stealing signs since the beginning of the game. One of the most notorious cases was exposed decades after it occurred. In 1951, the New York Giants won a three-game playoff on Bobby Thomson’s famous home run off Ralph Branca of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The clubhouses at New York’s Polo Grounds were in dead center field, some 500 feet away from home plate. Manager Leo Durocher, that era’s version of Cora, installed a utility player named Henry Schenz with a telescope at a window in the clubhouse to steal signs by peering at the opposing catcher. In its simplest form, “one” may signal a fastball and “two” a curve.

In today’s game, the signs are shuffled and more intricate.

The Giants had rigged an elaborate electronic system to convey signs from their bullpen to the home dugout. It was a hand signal from Schenz to the bullpen and then a wiring system which set off a buzzer as those stolen signs were relayed to their dugout. That was strictly illegal in baseball even back then.

“You just have to be prepared as a team,” Cora said. “That's the only thing you can do. Stealing signs and tipping has been going on forever. I learned in Miami. In college, we used to do it. I don't know if that's good for the program, but, yeah, we used to do it.”

[beauty_quote quote='"Stealing signs and tipping has been going on forever. I learned in Miami. In college, we used to do it. I don’t know if that’s good for the program, but, yeah, we used to do it." - Boston Red Sox manager Alex Cora']There are much more sophisticated means to transmit data these days. The Red Sox were fined late in the 2017 season when a Boston trainer was seen using his Apple Watch to relay stolen signs during a game against the New York Yankees, who filed the complaint after reviewing video taken of his actions in the Red Sox dugout. Though iPads and Apple watches are allowed to be used in dugouts to disperse information, contact from outside the dugout to these devices is expressly prohibited.

In the National Football League, coaches are allowed to sit in the press box and relay plays and formations to their counterparts on the field. Not so in baseball, where the only contact allowed on strictly monitored phones is between the dugout and the bullpen, regarding possible pitching changes, or from a replay specialist watching video tape to refer close calls to managers for challenges and review.

Sources: The Indians warned the Red Sox about a man named Kyle McLaughlin taking pictures of their dugout for the Houston Astros. MLB also looked into an August incident in which Oakland alleged an Astros sign-stealing scheme.

News at Yahoo Sports: https://t.co/P1t6sqhoQc pic.twitter.com/MHEP2yimWC

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) October 17, 2018

In 2016, the Yankees were sanctioned by MLB for misuse of their dugout phone.

Cora was a bench coach for the Astros in 2017 and wasn’t involved in the Apple watch incident.

The subject of technological cheating — devices, camera positions and video room communication — was addressed in early November when general managers held their annual meeting with MLB officials.

“We spent a lot of time on it, and got good suggestions,’’ said Dan Halem, the deputy commissioner, during an end-of-meetings conference with the media. “I think the real issue is giving clubs comfort that other clubs are not using electronic technology to steal signs. We took a variety of measures in the postseason to give clubs comfort that the rules are being enforced. We got some additional suggestions on things we can do. I’ll talk to the commissioner who will make the decision whether we should continue protocols we put in place during the postseason, or whether we should add anything."

To be sure, the union that represents the players is also monitoring the situation.

“We’re paying attention to it,” said Tony Clark, a former player who is now executive director of the MLB Players Association. “We have to pay attention to it. It’s all in gamesmanship, but we have to be concerned that how it manifests itself on the field doesn’t take away from the integrity of the game itself.”

Going back to that seminal game on Oct. 3, 1951, at the Polo Grounds, did Thomson have the sign for Branca’s pitch that day? Branca always believed he did.

“Stealing signs is nothing to be proud of,” the now deceased Thomson told the Wall Street Journal in 2001. “Of course, the question is, did I take the signs that day?”

Thomson equivocated several times when asked if he was given the stolen sign. In the end, he denied taking it.

“My answer is no,” he said. “I was always proud of that swing.”

Pitch tipping

Clayton Kershaw was sailing along in Game 1 of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ 2014 NL Division Series. The Dodgers had a 7-1 lead over the St. Louis Cardinals heading into the seventh inning with the left-hander masterfully controlling the game.

Kershaw suddenly fell apart, giving up four consecutive singles. Before he left the game, Kershaw gave up another single, struck out two batters and surrendered a three-run double.

The Cardinals won the game, 10-9, and the best-of-five series in four games. Kershaw beaten again in Game 4.

Why did Kershaw lose it so quickly in that first game?

The Dodgers looked at the video and discovered Kershaw was tipping his pitches from the stretch, according to Logan White, the former vice president of amateur scouting for the team. Watch Kershaw in the stretch. As he starts his motion toward the plate, he has the unorthodox style of raising both arms to full extension high above his head, glove hand meeting pitching hand.

[beauty_quote quote='“Stealing signs is nothing to be proud of." - Former New York Giant Bobby Thompson']The Cardinals, then managed by Mike Matheny, a former catcher, were adept at reading him.

“He was tipping his pitchers up here,” demonstrated White, who left Los Angeles shortly after the 2014 season to become pro scouting director for the San Diego Padres.

The Dodgers advised Kershaw, but he wouldn’t admit it or make adjustments. Kershaw is more circumspect these days.

“I think everybody goes through it at some point in their careers,” the now 30-year-old Kershaw said during the 2018 World Series. “Usually when you're younger, people can pick you apart, and over time figure out things. And same thing with me. I think when I was younger I did some things like that and figured some stuff out, and some guys helped me out with that.

“But this series in particular, obviously there's stuff coming out about all sorts of ways to get signs. Everybody is paranoid, so everybody is taking the necessary precautions.”

The probability, though, is Boston beat the Dodgers at that game inside the game.

Players from Puerto Rico grew up learning to read pitchers tipping their pitches. Alex Cora and his older brother Joey, now a base coach with the Pittsburgh Pirates were both major league infielders.

Brothers Sandy Jr. and Roberto Alomar also came from a Puerto Rican baseball family. Sandy was a great big-league catcher and is now first base coach with the Cleveland Indians. His younger brother, Robbie, a Hall-of-Fame second baseman, is now a special advisor for the Toronto Blue Jays.

Their father, Sandy Sr., was a big league infielder, coach and mentor. He taught his two boys the vagaries of how to use their special talents to get an edge in the major leagues. No one was better at reading a pitcher than the younger Alomar.

Both Coras played for Alomar Sr. at Caguas in the Puerto Rico Winter League and played with Robbie Alomar.

“I mean, his baseball IQ is off the charts. Robbie tries to take advantage of every little detail,” Alex Cora said. “At that time, we knew this guy was going to be a Hall of Famer. I still remember there's one out, he’s at second, and we're playing in Mayagüez. That’s like the biggest rivalry for us in Caguas.

“And the catcher was flipping the ball back to the pitcher, back to the pitcher, back to the pitcher. We're talking about Robbie Alomar, one of the best players in the big leagues, and he's playing winter ball. Pitch, flip it and he took off to third. We were in awe. Like, if this guy is doing this, we better start playing that way.”

Eduardo Perez

Perez was the son of an elite Cuban player and grew up around the Big Red Machine of the Cincinnati Reds and Hall of Famers Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Perez’ father, Tony. When his father was playing with Rose and Morgan for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1983, Eddie was 13 years old, sitting in the Phillies dugout at Veterans Stadium. He said he was flipping sunflower seeds with pitcher John Denny and somehow one hit Rose, who was watching the game. Rose summoned the kid. He didn’t yell at him. He didn’t kick him out of the dugout. This is what Rose did:

“He reprimanded me and said get your [butt] over here and he made watch the game,” said Perez. “I had to learn everything the pitcher was doing. I could talk in between, but I couldn’t miss a pitch. At that point I didn’t know a fastball from a curveball. I’d never seen a slider my whole life. Pete taught me all the tendencies. What a pitcher would do if he threw a certain pitch.”

After his eye injury, those lessons saved Eddie Perez’s career.

“This was a blessing for me,” he says. “After the injury I had blurry vision. It was 20-80, 20-15 before the injury. I couldn’t see much.”

But Perez had his ways.

To pass eye tests during the annual pre-spring physical, he memorized the last line of the eye chart. The smallest letters and numerals.

“Let’s just go to the 20-20,” he’d tell the doctor. “I had it down.”

Even today, as a broadcaster, he still utilizes his reads of pitchers to analyze the games.

“I can’t help it when I’m watching the game, when I’m broadcasting the game,” Perez said. “It’s part of my DNA now.”

Legal cheating is a part of baseball’s DNA, too, and always will be.

Barry M. Bloom has been a baseball writer since 1976, and a National Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1992. His sometimes award-winning national reports and columns appeared on MLB.com for the past 16 years, until recently. He’s now a contributing columnist for Forbes.com.