'Rezball' rises to level of religion on Navajo Reservation

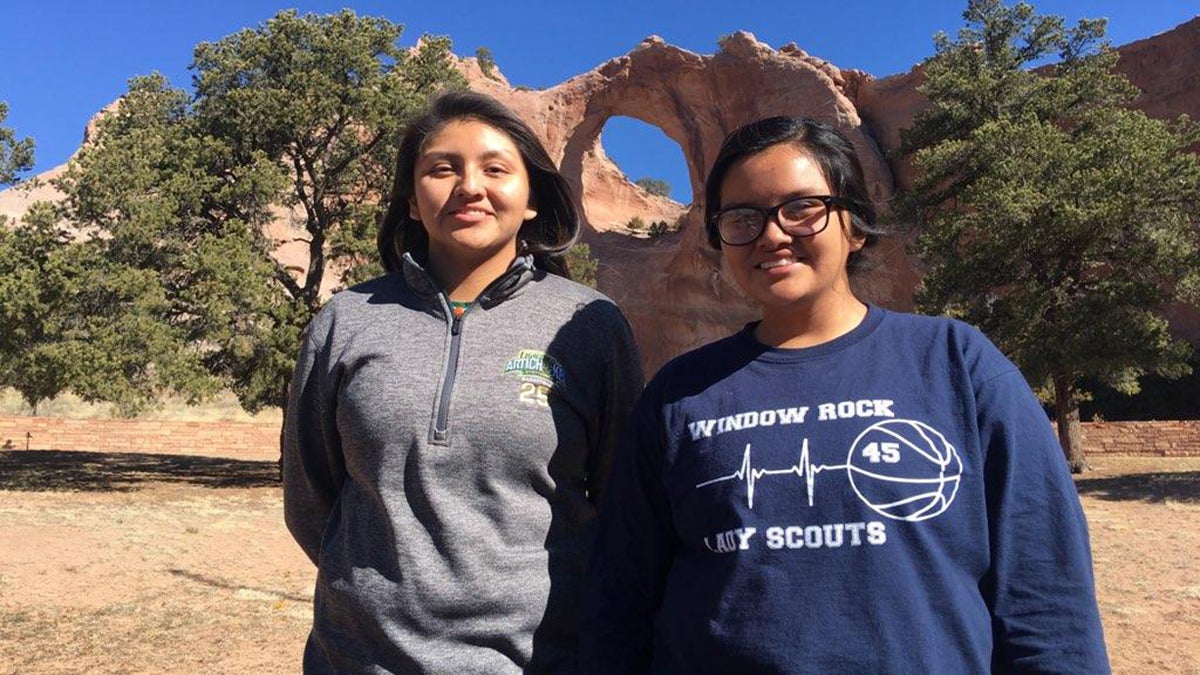

In the summer of 2015, Alicia Hale was training like mad for her senior season of basketball at Window Rock High School on the Navajo reservation in Arizona.

She ran with her mother Clarissa and her younger sister Ashley nearly every day at 5:15 a.m. She hit the weight room under the guidance of former Window Rock boys basketball coach Raul Mendoza.

Two goals drove her forward: play basketball in college and get a degree that would enable her to return to the reservation with a job.

College basketball is a dream for many athletes on the reservation and Alicia Hale is one of the few who successfully made the move up to that level. The sport is almost a religion on tribal lands across the country and as such, it is worshipped by players and fans.

So much so that several high schools on the Navajo reservation play their games in multimillion dollar arenas, not gymnasiums. These arenas hold upwards of 7,000 people and come equipment with stadium seating, VIP areas, state-of-the-art electronics, numerous concession stands and four-sided scoreboards that hang above the floor.

The locker rooms have custom carpet with the mascot stitched into the fabric. They have padded chairs with the mascot emblazoned on the cushions. They feature rich wooden lockers that are nicer than those of many Division I colleges.

Fans will wait in line for hours in the freezing cold, even overnight, to purchase tickets. The games are wild, frenetic bouts of fast-paced action fueled by screaming crowds who invest much of their being in the outcome.

The style of play, which resembles a track meet on hardwood, earned the nickname “rezball” over the years.

Coaching at high schools on the reservation can be a hazardous trade. Instant success is required. Expectations reach far higher the domed ceilings of the arenas and the resulting pressure on the athletes is immense.

It was in this environment that Hale thrived. She navigated her high school career with a calmness that was admired by her younger sister.

“She kept her cool all the time when she was in high school and college,” Ashley said.

Now, with the summer of 2018 on the horizon, she has accomplished her first goal and is halfway through the second. Hale is two months shy of graduation from Scottsdale (Arizona) Community College where she played basketball for two years and has an associate degree waiting for her acceptance.

“I learned a lot being far away from family,” she said. “There’s always an outcome or a consequence to whatever you choose to do. Just know what your parents taught you and input that into where you are now.”

Hale is the eldest of four children. Her transition from high school to college was a first-time experience for everyone and like many families in their situation, the Hales had concerns.

Alicia played numerous tournaments in Phoenix over the course of her basketball career, so Scottsdale was not some strange land full of unexpected wonders and obstacles. But there are stark differences nonetheless.

The most prominent is the nightlife. The sale of alcohol is prohibited on the Navajo reservation. There are no bars. There are no wine lists in restaurants. Addiction has taken a bitter toll on Navajo lands, where employment and poverty are still severe problems.

By contrast, Scottsdale is a playground for the wealthy of Arizona and others from around the world. Its hills are littered with multimillion mansions, many of which are second or third homes for their owners. The city thrives on revenue from the sale of expensive food and drink. Temptation is everywhere.

“If you get into drugs and alcohol, things are not going to fall in place for you,” Clarissa advised her daughter. “It’s going to be harder to bounce back if you get in trouble.”

Knowing this, Hale’s parents did what many parents do when their first child goes off to college: they offered steady and fervent prayers for guidance.

“Keep balance with Mother Earth and your foundation,” Alicia’s father, Vernon, said. “You learn from generation to generation to stay focused, stay grounded and keep your purpose in life.”

He then put it more simply. “As long as you’re doing what’s right, it shouldn’t be a problem.”

Alicia did what was right. She kept her grades up. She helped her team on the court. She learned independence and responsibility. And perhaps mostly importantly, she learned strength through adversity.

Her basketball career did not have a triumphant ending. There was no soaring musical score as in a Hollywood movie.

It ended on the final Saturday of December 2017 with her face down on the floor in agony.

Scottsdale was hosting its annual tournament over the holiday break. SCC was playing South Plains College from Levelland, Texas. The Artichokes had lost their first game of the competition badly, but won their second. They desperately needed a win in the third game.

Alicia’s playing time increased against South Plains. She excelled on defense and grabbed several rebounds. SCC had been trailing but fought back to take the lead.

Her parents were in the audience that day. Clarissa was filming the game for a highlight reel.

At one point, there was a scrum for a rebound. Players battled under the rim. Alicia’s left arm got tangled with an opponent as they wrestled for the ball. The whistle blew to end the play. Alicia and the opponent crashed to the floor.

“Everyone went up for the rebound and I knew she was in the middle of it,” Clarissa said. “Then everyone cleared the area and she was the only one laying there. When you watch the tape back you can hear it all go quiet and I just shut the camera off.”

An opponent landed squarely on Alicia’s left shoulder, dislocating it instantly. The SCC trainer popped it back in but the damage was severe.

“When that happened I just broke down and cried,” Clarissa said.

The experience was difficult, to say the least, but Alicia Hale speaks about it matter-of-factly now. She was in a sling for a couple weeks and then had surgery on January 19. She was in a bigger sling after the procedure and had to reorient her life to compensate for the injury.

She slept in a recliner for a month and could only wear button down shirts. She learned to cook one-handed. She was finally out of the sling in mid-March. Now, she can sleep in her bed. She can wear pullover shirts again. But in rehab, she can only lift two-pound weights. By comparison, a gallon of milk weighs roughly eight pounds.

Before the injury, she was open to basketball opportunities beyond SCC. Vernon hoped she might get a look from Arizona State University, though he knew it was probably a long shot.

The next step is now business school at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff and it’s a good choice for the entire Hale family. The school is closer to home and Alicia is excited to get back to the snow in the upper elevations.

She likes math and plans to major in accounting. When she graduates, she wants to use her degree to get a job on the reservation and fulfill her second goal.

And she gets to cheer for her younger sister. Ashley will be a senior at Window Rock High School this year and she has studied her older sister closely. She spent summers with Alicia in Scottsdale to train for basketball.

“I want to get offers like my sister, but I just have to work at it,” Ashley said. “She always kept her grades up, so I did that too.”

Alicia’s days of rising at 5 a.m. to run the sidewalks of Window Rock are likely in the past, but Ashley and Clarissa will keep the summer tradition alive for one more year. After that, there will be another round of prayers for guidance as Ashley goes off to college.

Chris Wimmer is an award-winning journalist for the Brenham Banner-Press in Brenham, Texas.

Related Articles

What the Arlee Warriors were playing for

Basketball at breakneck pace a way of life on Navajo reservation