How the NBA Opens Doors for Diverse Coaches Without its Own ‘Rooney Rule’

Why this matters

Heading into its upcoming season, half of the NBA's coaches are Black. For a league that is made up largely of Black athletes, this is a meaningful milestone. But there's no guarantee this proportion remains, and women coaches of all races have had a much more challenging time pushing for opportunities.

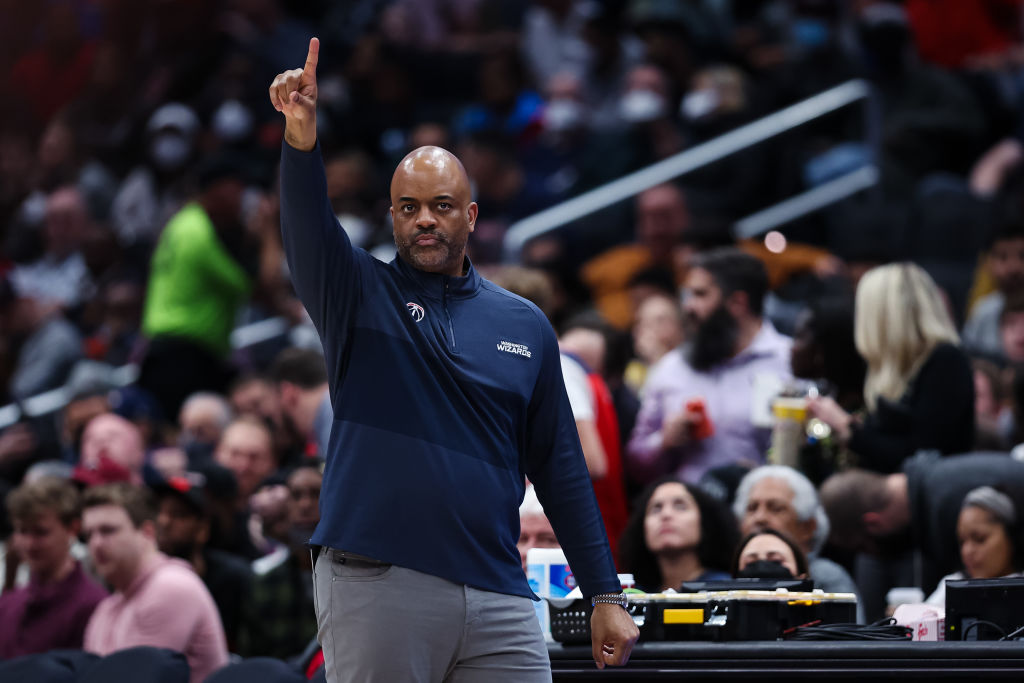

When Wes Unseld Jr. was hired as the head coach of the Washington Wizards in September 2021, a substantial, meaningful part of his personal history was intertwined with the team’s. He’d spent five years working as a scout under his father, a Wizards icon, in the same arena he would soon coach in, and well before he could walk, he was trundled in and out of locker rooms when Unseld played for the franchise. Unseld Jr. knew the place down to the nicks and grooves on the court, muscle memory tacked onto the 16 seasons of his own coaching experience–and still the job, so long worked for, felt to him like a “leap of faith.”

“Even when you feel you’ve prepped yourself your whole life, or you’ve geared your career in the last X numbers of years where you feel like you’ve put yourself in positions to take that next step, that next step is still a leap of faith, because you’ve never done it,” he says.

In his first official news conference with the team, Unseld Jr. recalled that in the process of his hiring, he’d find himself on the phone with Washington president and general manager Tommy Sheppard as often as six times a day. So when the call that changed his career came, it was nothing out of the ordinary, though he was honest about a feeling of trepidation in the moment.

“Of course, there’s that excitement about finally achieving a goal, something you’ve worked tirelessly for for two-and-half decades for it to come to fruition,” Unseld Jr. says. “The trepidation is — Oh, now what? Because there is no handbook after you get the job to say here’s step one, step two, and going down the line. You’re kind of flying blindly.”

Every first-time head coach has shouldered a similar weight. This is especially true in a league as competitive and unflinching when it comes to cutting coaches loose as the National Basketball Association, which has the shortest average coaching tenure among the United States’ four major professional sports leagues since 1990. And for a first-time Black head coach, the weight of expectation is made heavier still by an awareness that the role historically has not been very diverse: Since the 1990s, the NBA has hovered around 30% head coaches of color, compared with 83% players of color.

Recently, however, those numbers have started to change. At the start of the 2021-2022 season, the NBA had 16 coaches of color, 13 of whom were Black. As of June 2022, half of the league’s franchises had Black head coaches, a meaningful and important benchmark. The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (TIDES), a part of the University of Central Florida, publishes annual studies on the racial and gender hiring practices in amateur and professional sports. TIDES awarded the NBA an A grade for the overall racial and gender composition of its coaching, front office, and league office hiring when compared to overall U.S. demographics in 2022 – second only to the Women’s National Basketball Association, which had an overall grade of A-plus.

Unlike the NFL, which uses the Rooney Rule in interviewing candidates for head coaching and senior football operations jobs to encourage racial and gender diversity in hiring (and scored a B in TIDES 2021 study), the NBA has no formalized, league-wide rule for hiring coaches or front office staff. Still, out of the major North American pro leagues, the NBA has recently established one of the best records on diverse, equitable, and inclusive hiring practices for its head coaches. This shift is promising but also requires further maintenance, ranging from initiatives on the part of the league and its coaches to continued pressure from those who want to see further progress in representation and opportunity for all kinds of coaches.

Interrupting Barriers

Change in the NBA is not a fluke. While the hiring of so many Black head coaches in the 2021-2022 season ultimately reflects the experience and expertise of coaches like Ime Udoka, Jamahl Mosley, Willie Green, Stephen Silas, and Unseld Jr., it was also the result of league-driven initiatives.

In 2019, the NBA launched the Coaches Equity Initiative (CEI) in partnership with the National Basketball Coaches Association (NBCA). The CEI, which Yahoo! Sports recently reported was shepherded on the league side by deputy commissioner Mark Tatum, works as a two-way internal support network of coaches, coaching candidates, general managers, and others to prepare emerging coaches for job opportunities and provide decision-makers with information on potential candidates. Informal, group mentoring forums were also introduced at the league’s tentpole events, like Summer League, where emerging and assistant coaches can hear from front office leaders and team governors on what they value in the hiring process.

"What we have been focused on at the NBA is how does the process for hiring a general manager, or hiring a head coach, or hiring any leader in our organization, how does that process happen? What are the barriers to inclusion that happen along the way?” says Oris Stuart, the NBA’s Chief People and Inclusion Officer. “And then what can we do, at every step, to interrupt those barriers?”

In addition to programming like the CEI, the direct pressure applied on the league by the NBCA is partially responsible for the uptick in diverse head coaching hires. During a visit to Dallas in February 2019, Stuart, Commissioner Adam Silver and President of Social Responsibility and Player Programs Kathy Behre met with then-Dallas Mavericks head coach and NBCA President Rick Carlisle. Carlisle shared with the group the concerns of several assistant coaches who felt they were being overlooked in interview opportunities for head coaching jobs. After several subsequent meetings between the NBCA and the NBA, it became clear there was a need for tangible, accessible resources that would help assistants gain exposure to team ownership and management.

Six months later, the NBA Coaches Equality Database was launched. A kind of invitation-only LinkedIn, the database allows candidates flagged by those in the league or NBCA to build out personal profiles to highlight their experience, approach to coaching, and personal markers and metrics of their success. The database currently holds more than 300 profiles of coaching candidates, and more than 100 front office decision-makers are registered with access to those profiles.

Related: The NBA’s First Mexican-American Head Coach is Always Working Toward a Way Back In

Unseld Jr. says that the database allows coaches to upload videos of themselves being interviewed. “You get a glimpse of them in front of the camera,” he explained. “That’s a tangible piece because while we can argue this and that, a lot of it is about optics. Can a person command the room? Can they have a presence? Because in this position, that’s a big piece of it.”

Another helpful feature? When an NBA coach of the month is elected, the entire staff of that coach is highlighted. Unseld Jr. says that amounts to “a great opportunity for decision-makers to get a glimpse into some of the assistant coaches, some of the lower-level assistants and staff members that maybe right now aren’t in the head coach conversation but down the line could be.”

A longer-tenured initiative of the NBA is its Assistant Coaching Program, started in 1988. Focused on assisting former and current players who have an interest in transitioning to the coaching side, it counts 200 alumni as members, including current Phoenix Suns head coach Monty Williams. While the ACP is certainly helpful for those who are already somewhat inside the NBA, it doesn’t necessarily work to expand the coaching pipeline beyond the league itself.

Another glaring gap in increasing NBA head coaching opportunities and diversity is finding ways to open up the informal hiring networks and practices that long have existed within the league. “I don’t know if it’s a conscious bias or more of a systemic issue that minority candidates just don’t have the relationships or don’t have the ability to get in front of decision-makers,” Unseld Jr. says, pointing out a relative lack of diversity in team ownership and front offices. “I think that’s probably the biggest gap that has to be filled.

“We look at other businesses outside of sports entertainment, and a lot of them are based on relationships. People that are well-connected; they’ve known each other from certain institutions or other avenues. If you’re not in that circle and you don’t have access to the decision-makers, it’s probably at your detriment.”

In this environment, personal advocacy becomes instrumental in assistant coaches getting noticed. When Unseld Jr. was an assistant for the Denver Nuggets in the NBA’s Orlando Bubble, Nuggets head coach Mike Malone publicly lauded him, noting Unseld Jr.’s defensive coaching was a main reason his team was able to make it to the Western Conference Finals. Though Malone was vocal in wanting to keep Unseld Jr. as an assistant, he was equally vocal in promoting him as a head coaching candidate, saying he’d be a “rockstar coach” when a team was smart enough to hire him and that to limit his scope to defense would be doing him “a disservice … he’s a basketball coach.”

Not all current head coaches with smart, tenacious assistants ready for upward mobility are as loud, adamant, or perhaps even aware that their star assistants could thrive in a bigger job somewhere else. “I think a lot of times when a job opens up, the top names are already on the board,” Unseld Jr. says. “So some of these potential candidates get excluded. I think it’s a great opportunity for disseminating that information and (having) it in a platform where it’s easily accessible.”

There’s no one reason barriers to head coaching diversity exist – which means there’s no single silver bullet for removing them, either. The people in the rooms where hiring decisions get made aren’t usually women or people of Color. The people with friendly access to those rooms aren’t, either. Tools like the Coaches Equality database are helpful, and so are an increasing number of diverse coaches opening up the coaching pipeline to informal networks of more diverse assistants. But that doesn’t fully solve the insular nature of the NBA’s extended head coaching pool. Season after season, there’s a sense that the same big names are shuffled around. Meanwhile, new talent from outside the league – college coaches, international coaches, and potential coaches now working as scouts, analysts, video coordinators and filling other coaching-adjacent roles – has a tough time getting a foot in the door.

Ultimately, there are only 30 head coaching jobs in the NBA. Opportunities are relatively rare. Disappointment is inevitable. Still, when openings happen and teams seem to have predetermined replacements in mind, everyone else gets frustrated. And frustrated people eventually look elsewhere.

‘Women Are Capable’

While men of Color in the NBA have become well-represented in the coaching ranks in recent years, women of all races are not seeing the same opportunities – and in many cases, they are leaving the league altogether.

“What we’ve seen in the past couple years is a little bit of an exodus of female coaches leaving the NBA ranks, which is both unfortunate and fortunate,” says David Fogel, executive director of the NBCA. “Fortunate, because they’re getting really great opportunities to further their careers and there’s some economic benefits with it, but we want to keep as much of that tremendous talent in the NBCA as we can.”

The most high-profile example is Becky Hammon, who left the NBA in the spring of 2022 to join the WNBA’s Las Vegas Aces as the team’s head coach. After eight seasons as an assistant with the San Antonio Spurs following a 13-year playing career, Hammon had long been thought of as the leading candidate to replace legendary head coach Gregg Popovich when he retires. (Popovich once told NBA TV’s Inside Stuff Hammon knew “when to talk and she knows when to shut up.”) Hammon also interviewed for open head coaching positions in the offseasons leading up to her eventual departure from the league, and while she could be candid with her frustrations, she publicly always maintained that the right fit just hadn’t materialized yet. Meanwhile, many of the male Spurs assistants she shared the bench with, such as James Borrego, went on to become head coaches.

Related: The 'Long Slog' of Women Coaches Trying to Break Into Men's Basketball

For so long, discussion around a woman securing a head coaching role in the NBA hinged on the concept of readiness. When Hammon was hired by the Spurs in 2015, the question was whether or not the league was ready – meaning players, front offices, and, by extension, fans. Over time, the consensus shifted. The league was ready, with stories (mainly written by women) providing various reasons. But even these articles, including first-person open letters from athletes like now-retired NBA player Pau Gasol, still centered on an outdated, largely sexist perception: that there was something to discuss. That the reasoning Hammon wasn’t ready – even as former players like Chauncey Billups and Steve Nash became head coaches without any prior experience – had something to do with her preparedness rather than the socal temperature of the time. There has always been a lot of cyclical discussion on her (or any woman’s) qualifications when the same concerns are not flagged for first-time male coaches – a lot of what now reads as stalling, if not outright sexism.

“She’s been ready,” says former Memphis Grizzlies assistant and current University of Notre Dame women’s head coach Niele Ivey, a friend of Hammon’s. “Man, I felt like [she] was really going to be that first person. Like everybody. I mean, she’s so talented.”

Ivey, a former WNBA player who went on to coach 14 years in the NCAA – first at Xavier, then at her alma mater Notre Dame under legendary Muffet McGraw – had a wealth of experience and fresh eyes she appeared primed to use in Memphis and beyond.

With no previous connections to the Grizzlies, Ivey was contacted by Memphis in the summer of 2019. She recalls feeling right away that the team was being deliberate about diversifying its staff. Under new, younger leadership led by general manager Zach Kleiman and head coach Taylor Jenkins, the franchise added multiple women in assistant coach roles, as well as others from the G League, NCAA, and overseas.

“For me, that made me feel like it’s not a Rooney Rule; they’re not trying to check a box,” Ivey says, noting that it took the team less than 24 hours to call her back with a job offer. “I really did do a great job and impressed the head coach the first time he ever had a conversation with me.”

For Ivey, returning to Notre Dame in 2021 as head coach, replacing her mentor, and becoming the school’s first Black woman head coach was a monumental opportunity – and, ultimately, one that she couldn’t pass up. Stll, her departure from the NBA after a single season reflects a larger trend: While the league is doing a better job of recruiting and attracting women coaches than ever before, it is struggling to keep them.

In 2019, there were 11 women working as NBA assistant coaches – but at the start of the 2021-22 season, that number had dropped to six. Natalie Nakase, now an assistant for Hammon in Las Vegas, in 2014 became the first woman to sit on an NBA bench during the Summer League with the Los Angeles Clippers. Head coach Ty Lue sent her to the G League when he took over in 2020, and she left the league less than 18 months later. Kara Lawson, who was an assistant with the Boston Celtics in the 2019-2020 season, served as shooting guru for point guard Marcus Smart and helped the veteran average the most points of his career. Lawson left the following year, hired by Duke University as head coach of its women’s team.

Generally, decisions to leave the NBA are driven by money and opportunity: Women like Hammond hit a career ceiling and realize that there’s more of one or both outside the league. “When the numbers are smaller, every coach that leaves, the impact is much greater,” Fogel says, adding that he is pressing the NBCA to “make sure there are opportunities where we can keep and cultivate talent in the NBA, and not have [women] leave to further benefit their career and maybe return at a later date.”

Stuart, the league’s chief people and inclusion officer, says that the NBA has taken a more active role in creating opportunities for women coaches by reaching out directly to teams that are hiring. And there are other signs – albeit small ones – that both hiring and retaining women is becoming a priority. This past January, Teresa Weatherspoon, a WNBA and Olympics icon and former college coach, asked that her name be removed from consideration for the next head coach of the WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury after the NBA’s New Orleans Pelicans made a deliberate push to retain her. Kristi Toliver, an active player with the L.A. Sparks, holds a dual role as assistant with the Dallas Mavericks, a position that saw her miss a month of her WNBA season’s start with the Sparks when the Mavs made it to the NBA Western Conference Finals. (Citing her busy schedule, Toliver declined an interview request for Global Sport Matters for this story.)

“Teams are purposefully and intentionally looking at women candidates – because they recognize the gifts they bring to the game; they recognize they are elite talent in terms of being able to contribute in unique ways to the success of their teams,” Stuart says. “So notwithstanding who’s in the room, I think there’s a broadening appreciation for the value that women coaches are bringing and can bring.”

Though Ivey has left the league, the reason she did so could be telling for women in similar roles in the long term. She credits McGraw with instilling in her the importance of leading young women intentionally. It’s that quality of mentorship that Ivey hopes to lend to her own athletes, “It’s not about the salary; it’s about impacting young women,” Ivey says. “For me, it’s the purity of coaching, and that’s why I love getting into it.”

In this way, strong female coaches like Ivey and other women who have come and gone from the NBA offer examples, mentorship, and entry points back in. They have intentionally begun to establish better and more equitable networks of their own, ones that could over time break down the barriers they faced.

“To be the first African-American female head coach at Notre Dame, I know that it’s important,” Ivey says. “I know it’s important being the first female assistant coach with the Grizzlies … so I feel like I’ve realized the magnitude of being a trailblazer, and I’m honored to be in that role. I’m hoping I can continue to work hard and do well so I can show CEOs, I can show decision-makers, that women are capable and that the things I do can open doors for other women.”

Men have coached women at every level of the game for decades. There is no special formula that differentiates readiness, or success, between female and male head coaches, only archaic barriers reinforced whenever the decision is once again put off. As for the immediate career livelihoods of the handful of women left in the NBA as assistant coaches, Ivey is succinct: It just takes one.

“I’m hoping that there is an organization that really gives a woman the opportunity. I mean, that’s really it. That’s it. It’s basically, you’re doing something that’s never been done before and being confident in that decision,” Ivey says. “There are many, many women that are qualified to take over an organization, an NBA program.”

Extending the Shelf Life

To achieve the diversity it strives for, the NBA must make it routine to open and maintain head coach pathways for as diverse a range of people as possible. But for now, coaches like Unseld Jr. and Ivey feel pressure to succeed – and create more opportunities for people like them in the future.

When asked whether she had a chip on her shoulder, Ivey jokes, “It’s like a Mack truck for me because I had to take over from a Hall of Fame coach (during a pandemic).” She recalled coming home after her first loss, half her players out with COVID-19 or injuries, and feeling the full weight of expectation for the first time.

“And I’ve had to, every day from my first year to second year to now, be OK and comfortable with that weight, because it’s never going to go away,” Ivey says. “I’ve learned how to move with it and shift with it. That’s what I tell myself. But it’s definitely heavy.”

Still, Ivey’s “why” are her players, wanting to “pour into them” the kind of confidence that was instilled in her by McGraw. In her first season, she says, she continually reminded herself, “I cannot be Coach McGraw” and could, as she had when taking a job in the NBA, only be herself.

Related: As Women’s Basketball Grows, Doug Bruno Wants To ‘Naturally Move It Forward’

For Unseld, the weight of expectation came more from the unique chance to help lead this new wave of Black head coaches in the NBA.

“You feel this, not pressure, we’re not the first minority candidates to have head coaching jobs. But to see the influx all at one time, we do have to set a standard,” Unseld Jr. says. “Myself, some of the other minority candidates, we talked about it.”

As with Ivey, Unseld Jr. grounds himself in his work by maintaining a sense of empathy, hard maintained in pro sports, and distilling it down to who matters – his players.

“It’s a dangerous rabbit hole to crawl into if you allow yourself to listen to all that outside noise,” he says.

It can be hard not to let the pressure of representation interfere with one’s ability to succeed. Even the most determined player-first coaches are going to buckle under that weight from time to time. Still, today’s coaches hope to do their part to create opportunities for those who are next.

“Whether you win or lose, this job has a shelf life. We get that,” Unseld Jr. says. “You want to make sure we’re good stewards. Hopefully, that helps maybe ease, if there’s any angst at all amongst decision-makers, (reminding them) that, hey, let’s take a look at some of these other minority candidates, given the track record and some of the successes that we hope to have.”

Monthly Issue

Progress vs. Power in Sport

In his 1996 book "In Black & White," Global Sport Institute founding CEO Kenneth L. Shropshire wrote that "the selection of the right person for a position in sports, both on and off the field of play, is extraordinarily subjective." That book prescribed reforms across levers of society to increase the representation of Black leaders in sport.

This issue continues Shropshire's exploration, with a particular interest in how those in power have shaped progress when it comes to diversity, for better and worse.