Diversity at the top: C-suites of sports franchises are changing

Why this matters

Diversity in coaching and management is often the focus in sport, but advocates are finding new opportunities in executive roles as well.

The relationship between performers of color and the majority-white business that finances their work is not a new structure in America, but it is particularly pronounced in sport.

In the United States, basketball stands out among major sports in how the demographics of executives and owners mirror those of the country. Football is trending in this direction but is not yet balanced between management and players. Other sports, such as hockey and baseball, are predominantly played and run by a white majority and therefore feature less of a disparity between the demographics of their executives and players. Yet at just about every level, a profound lack of diversity among the top business executives residing in the C-suites of sports organizations remains.

The problems when it comes to inclusiveness are foundational, sports executives said. Simply put, sports organizations in the past cared far less about hiring diverse executives and creating a diversified viewpoint at the top of their business.

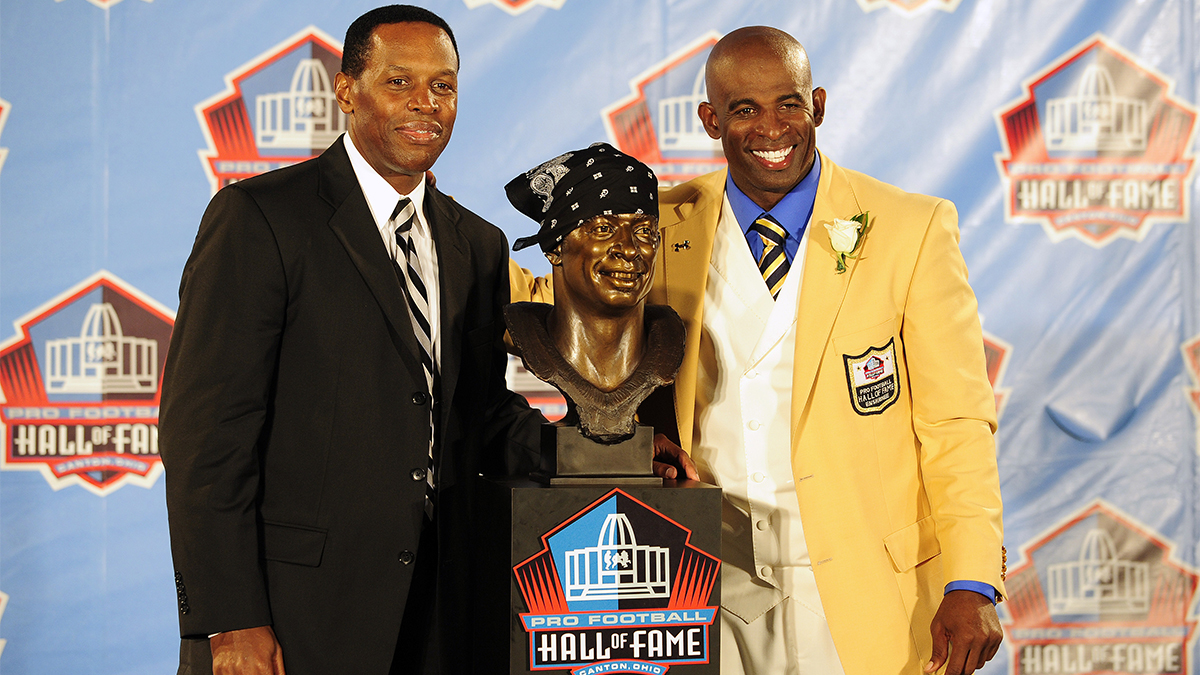

Trailblazers such as tennis agent Bill Shelton, National Football League agent Eugene Parker and the Global Sport Institute’s Kenneth Shropshire were instrumental characters in the development of sports business by paving the way for younger people of color to find increased opportunity in the industry. While the offices of sports franchises around the country are more diverse than they used to be, progress continues.

Trailblazers are proud of the progress made

The most important change may be in the numbers.

“As the industry has evolved over the years, you see more people of color have access to participate in those positions and have benefited from those who have entered into the space before them,” said Arthur McAfee, the NFL’s senior vice president of player engagement.

When McAfee started his career in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), there was no general counsel’s office. During his time in the industry, new opportunities have opened in that office and many of the lawyers are people of color, he said.

McAfee appreciates that rapid change in his section of the industry and uses his place within pro football to make changes toward inclusivity smoother for players, fans and business people.

“Athlete perception is the primary overall concern,” McAfee said. “Those athletes with diverse backgrounds have experiences that may not relate to the general public, but that people are interested in sharing, and oftentimes my observation has been that those unintended biases that go unnoticed are broken down.”

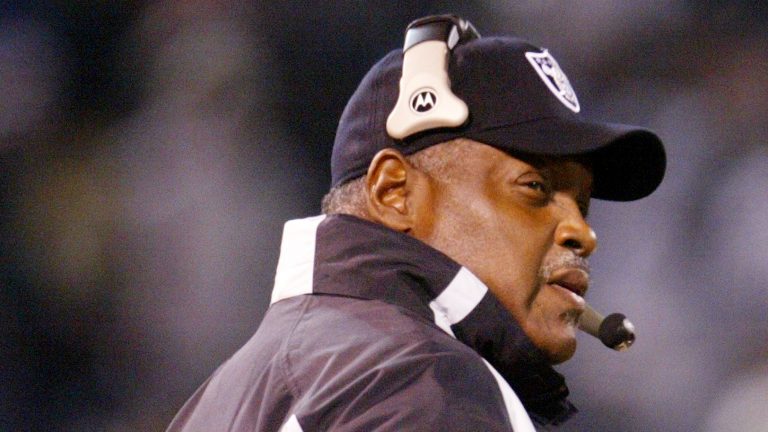

The NFL is particularly fertile soil for a conversation about race. The league is ensnared in an ongoing debate over freedom of speech by players who protest social injustice on and off the field. It also constantly makes adjustments to the way it treats and empowers athletes.

“As the industry has evolved over the years, you see more people of color have access to participate in those positions and have benefited from those who have entered into the space before them.” - Arthur McAfee, the NFL’s senior vice president of player engagement.

According to The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida’s Annual Race and Gender Report Card from 2018, 72.6 percent of NFL players were men of color; 11.7 percent of team executives at the VP level or above were people of color. In the league office, where McAfee works, 28.3 percent of employees were people of color.

The NFL has received an A-minus grade each of the past nine years in Dr. Richard Lapchick’s analysis. Grades show how closely a league’s representation of a minority group mirrors that of the nation’s demographics. Leagues receive an A grade for a given category if at least 24 percent of those holding that job are people of color.

It follows that McAfee would provide immense value to the NFL -- he is African-American, working as a liaison between players, fans and other C-suite stakeholders for NFL corporate partners.

Arizona State University Vice President for University Athletics Ray Anderson sees his role as somewhat similar to that of McAfee at the NFL. Anderson must bring together performers on the field of play and the people who consume sport at the college level. He sees his role, moving from player to coach to university official, in part as “sensitizing people to the differences that do exist” between them, even down to the personal relationships that connect players and coaches.

“Race certainly plays a role and can play a very positive role,” Anderson said.

Lapchick’s research found an increase in the number of Division I ADs and NCAA VPs in 2018, which Anderson believes will improve relationships and make college sport better.

Anderson, a former sports agent with his own firm, AR Sports, and Chief Administrative Officer for the Atlanta Falcons from 2002-2006 among many other accomplishments, has worn many hats in sports. Yet throughout his career, he said he has tried not to make a big deal of his own race.

Nevertheless, Anderson’s racial identity helps him forge connections with his student-athletes and their families. As an AD, it has been more of a “comfort-inducer,” he said.

“When I’m able to combine my legal and business background with the fact that I am African-American in a position where you don’t find a lot of us, race plays a role by having a different perspective in a lot of instances,” Anderson said. “There is a different level of believability in what I’m doing and saying that maybe in some other cases don’t exist.”

Speaking directly with athletes and their parents can create even better connections, Anderson said. Those who haven’t done their homework before visiting Arizona State are often pleasantly surprised when they meet him the first time.

“When I’m able to combine my legal and business background with the fact that I am African-American in a position where you don’t find a lot of us, race plays a role by having a different perspective in a lot of instances. There is a different level of believability in what I’m doing and saying that maybe in some other cases don’t exist.” - Ray Anderson, Arizona State University's Vice President of University Athletics

“Very rarely do you see a black administrator at a high level and certainly not the AD, and they are not shy at all about saying it is a big factor in the decision we are about to make,” he said.

The value of that bond is obvious to Anderson. With the support of ASU President Michael Crow, Anderson has tried to maintain it across his department, prioritizing diversity and inclusion when he hires people.

Anderson was part of the group that helped develop the NFL’s Rooney Rule, along with namesake Dan Rooney, the late Pittsburgh Steelers owner. Since it was instituted in 2001, the league has tinkered with the Rooney Rule, which required teams to interview at least one person of color for vacant head coaching positions. The most recent adjustments expanded the rule to front office positions and mandated that candidates come from a list of qualified coaches the league helps draft.

Anderson also led efforts this decade to create a process similar to the NFL’s Rooney Rule in college sports to force schools’ to find people of different backgrounds when hiring for positions at the highest levels. While that resulted in a public pledge from schools to focus more on diversity, Anderson said, “at the end of the day, it’s still the presidents and chancellors’ decision in their own institutions.”

The same could be said of NFL owners, who seldom turn to minority candidates for C-suite positions. Minnesota Vikings Chief Operating Officer Kevin Warren is the only African-American executive at the vice president level or higher in pro football. He has held that title for some time. He said he was excited by the opportunity in Minnesota and within the NFL to improve the business and the product for fans.

Warren was a college athlete and his brother played in the NFL. That familiarity with the game combined with his own career in sports law made a transition to pro football natural. He led the Vikings as they built a new stadium, played host to Super Bowl LII, and installed women and people of color in senior leadership positions. His success exemplifies Warren’s vision as a person of color at the top of an NFL team.

However, he is less forthcoming about the impact of race in sports business than Anderson or McAfee. Warren said he believes it’s the passion of sport that connects people of different backgrounds, rather than racial differences.

“One of the beautiful things about sport is it has a chance to bring a wide range of people together and to make an impact and to change the world,” Warren said. “Regardless of race, religion, color, ethnicity, (it) brings people together.”

Thinking creatively on a smaller scale

Even veterans of the industry agree the work is ongoing to open more avenues for people of color at the highest ranks of sport.

Based on Lapchick’s continued research into what separates institutions that value diversity from those that do not, he said, “The keys to diversity and inclusion are to always have a diverse pool of candidates for each position to increase the number of women and people of color.”

Shaina Weil is an entrepreneur who embodies the intersectionality Lapchick believes is the key to success. Weil is an African-American sports marketing professional and the CEO of Minorities in Sport. Weil was working for a company that was close to folding and, with no one to turn to, she set out to find people who could relate. That was the inspiration behind the group chat that became Minorities in Sport.

“A lot of the rooms that I was in, I was the only person of color,” Weil said.

Sensing she was not the only one dealing with such stress, Weil set out to use her company to open the door for “people of color to feel like they have a safe space to come and talk about things they may not be able to speak about in the office.”

The original group chat began with 10 close friends but now counts more than 1,000 participants from across the world of sport.

“One of the beautiful things about sport is it has a chance to bring a wide range of people together and to make an impact and to change the world. Regardless of race, religion, color, ethnicity, (it) brings people together.” - Kevin Warren, Minnesota Vikings Vice President of legal affairs

Eventually, the chat, hosted on the app GroupMe, helped Weil, a social media manager, land a new job, and it has provided important help for others as well. One chat member was working in the NFL as the Colin Kaepernick situation unfolded. She noticed that within her office kneeling was not supported, and she felt uncomfortable expressing their feelings on the matter. To make things worse, a fan found the NFL employee’s email address and reached out with inflammatory thoughts about African-American people related to player protests, calling him the N word and frightening the employee.

That member turned to Minorities in Sport as a place to bounce ideas and reclaim their security.

Weil knew situations like that were all too common for people of color in professional settings, and she realized the larger impact her company could have as a source of education for people who have never dealt with contempt and discomfort over their racial identity before.

“When people talk about diversity and inclusion, a lot of companies don’t know what that means,” Weil said.

Now, Weil is attempting to grow and monetize the company by forming partnerships and hosting events. She hopes it can create positive change by giving companies better access to people who look and think like segments of fans who are rarely considered.

“Consumers having direct contact to their brands and their teams has forced everyone across industries to look back at who they have in the room,” she said. “You make more money because you’re reaching more audiences; you don’t become one of those brands that does something insensitive.”

Some sports organizations are more willing to accept new voices than others. While the NFL is constantly tinkering with how it addresses diversity, the NBA has made empowering all employees a priority, said Aaron Ryan, who worked in the league for 22 years before leaving to run a soccer branding company.

Ryan, who is African-American, was most recently the CEO of the NBA 2K League, a first-of-its kind esports league run and funded by a pro sports league. The role was a natural step for an executive who made a career of putting basketball in front of new fans. He said diversity is the core of basketball’s identity, and he took pride in bringing to fans the stories of how and why players are inspired to step on the court.

“Consumers having direct contact to their brands and their teams has forced everyone across industries to look back at who they have in the room. You make more money because you’re reaching more audiences; you don’t become one of those brands that does something insensitive.” - Shaina Weil, CEO of Minorities in Sports

Individual stylings stand out on the court, Ryan said, and fans absorb the game up close. While the NBA was once coined too black, he said the league made the diversity of its players core to its identity.

“The league in and of itself was an underdog,” Ryan said. “It’s always been a league fighting for exposure and fighting for the story of those who didn’t have the megaphone to tell it.

“It’s not something we’ve had to work hard to tap into, but it’s a part of who the NBA is.”

The same variety of backgrounds and storytelling opportunities stuck out to Ryan in soccer when he took over running Relevent Sports, the company founded by Miami Dolphins owner and philanthropist Stephen Ross. At Relevent, Ryan’s goal is to bring international soccer to an American audience, and he sees the same potential for his background as a person of color playing the sport to be valuable in that role.

Regarding diversity at Relevent, Ryan said, like Warren in Minnesota or Anderson at Arizona State, it is his goal to hire with inclusiveness in mind.

“In the greatest companies in the world, it’s not something they do to feel better about themselves, it makes their companies more successful,” he said.

‘We have an opportunity to make it even better’

Cultivating diversity in a meaningful way behind the scenes of the sports industry will require a reconsideration of what such changes mean, said Anderson.

“If there’s a level playing field, than everybody is going to get a chance to participate in a better effort to raise the whole level of the leadership that we’re trying to assure for student-athletes,” he said. “If the best people, no matter who they are, are getting a chance to get in these positions, then everyone will benefit.”

As the NFL’s senior vice president of player engagement, McAfee’s job is to organize and make space for players by opening opportunities for them directly. A great example of the challenge of his task is the NFL Broadcast Bootcamp, which gives players experience in the booth analyzing and calling games. The program already has a perception of prioritizing white players, McAfee said, but “our goal is to make sure that all the players in this space have the ability to have the same access to make the connections for those particular careers as they leave the NFL.”

It would be a broad task to change the perception of every fan, reporter or corporate partner at once, and of course all people come to the table with their own history and perspective.

“Working in an inclusive and diverse environment is a strategic advantage. Having people from different backgrounds and representing different vantage points in society is good for business.” - Aaron Ryan, Relevent Sports

“We all grow up and live in certain areas, so we tend to stay in what we know,” Weil said before adding it is up to all parties to prioritize different perspectives for the sake of better business.

Ryan agreed.

“Working in an inclusive and diverse environment is a strategic advantage,” he said. “Having people from different backgrounds and representing different vantage points in society is good for business.”

But how to go about it? You can’t force change on people, Anderson said, otherwise it risks generating more pushback than it would genuine education.

“People have to commit to being deliberate about diversity and inclusion,” he said. “You can’t look for excuses like there aren’t enough candidates, this might not be the right cultural place, it’s hard to get people to be interested in this location.

“Absent that in my view, it will always be just talk.”

The general feeling of all those interviewed was as people with the power to bring about positive change in the industry, the lack of representation for people of color in sports business was a challenge rather than a chore. From the early pioneers who got a foot in the door to the people working on these issues today, the lineage has come from those who prioritize giving others a chance.

“I like it as an opportunity,” Warren said. “We have an opportunity to make it even better.

“It’s nothing to be negative about, we have to look at it as great chances.”